Bemis / Ransom House - Table of Contents.......... E. H. Butler House

Dog on a High Pitched Roof:

The Question of Silsbee in Buffalo

by Austin M. Fox

TEXT Beneath the Illustrations

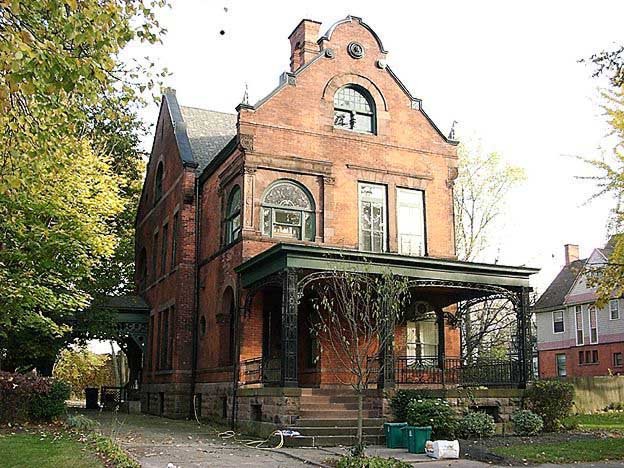

| The photos below were taken in 2000 and are NOT part of the original 1986 Spree article. The captions are excerpted from the article. Bemis-Ransom House, 267 North Street  Bemis-Ransom House The Romanesque dignity of the Bemis-Ransom house at 267 North across from College Street is guarded by its watchful gargoyles and its castle-like battlements  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House Terra cotta ornamentation ... Bull's eye window  Not a dog but a catamount (mountain lion) this gargoyle atop the gable peak at 267 North snarls a warning to any evil-doer.  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House  Bemis-Ransom House |

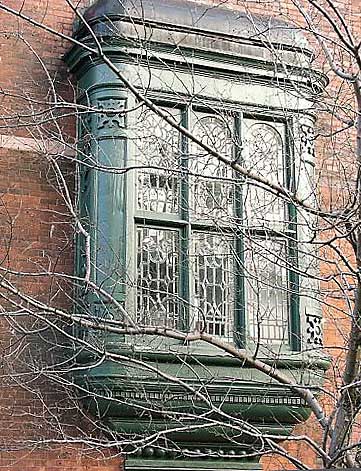

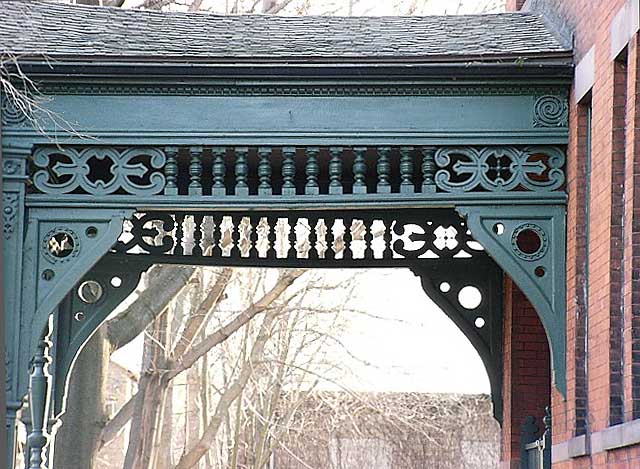

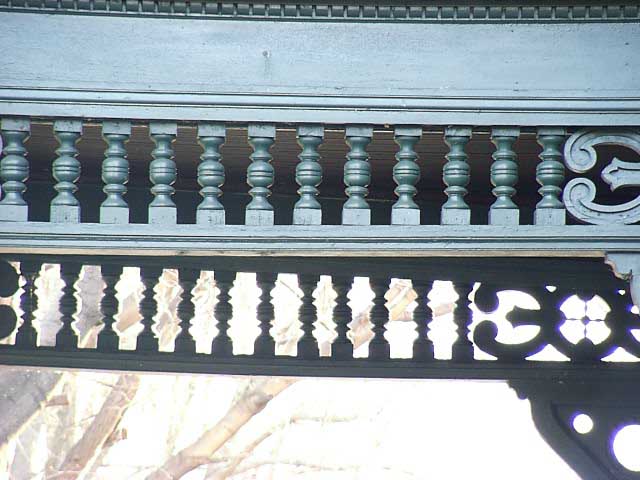

Edward Butler House 429 Linwood Ave. Edward Butler House Its round-arched window openings, pronounced drip moldings, and medieval ornament suggest the Romanesque origins of the former E. H. Butler house at 429 Linwood near West Ferry. A third gargoyle once sat at the peak of the Flemish gable.  Edward Butler House Three bull's eyes  Edward Butler House  Edward Butler House Eastlake stained glass window  Edward Butler House  Edward Butler House  Edward Butler House This oriel window on the south side of 429 Linwood shows unusual dog-tooth medallions, a ball molding, and fine curvilinear leaded-glass.  Edward Butler House Eastlake style  Edward Butler House  Edward Butler House |

Dog on a High Pitched Roof:

The Question of Silsbee in Buffalo

by Austin M. Fox

The attributing of notable buildings to the proper architect often requires considerable sleuthing. Unlike painters, writers, and certain vain criminals, architects usually do not put identifications on their work; Ordinarily, they sign their plans and drawings but not their buildings. There are exceptions, of course, like the HHR for Henry Hobson Richardson entwined in the Romanesque decoration on the facade of Austin Hall in the Harvard Yard, and there is the neat McKim, Mead and White marker in the handsome tile floor in front of the doorsill of the Williams-Pratt house (now Paul Snyder's corporate headquarters) on Delaware near North.

The custom of architectural anonymity, therefore, often makes the problem of attribution difficult for the architectural historian. In the absence of documentation or reliable oral information, he has only one trail to stalk for clues, and the Holmesian scent along the way is often faint. Like the handwriting "expert," all the architectural historian can do is to compare the handwriting sample (the building in question) with a known example of the person's calligraphy (a documented building). One notes, so to speak, the way the t's are crossed, the i's dotted, the letters slanted, and other telltale signs. One also studies more subtle linguistic qualities, such as the rhythms of the building's language. A student of literature who did not know Hemingway's or Faulkner's handwriting could quite reliably identify a holograph passage from either writer by the unmistakable cadences of each one's prose.

"Poetry," Robert Frost once said, "is the sound of the voice intertwined with the words." Architecture, one could say, is the sound of the designer's voice intermingled with his architectural vocabulary. The German philosopher Schelling once observed that architecture is frozen music. Music and poetry being similar, a person could justifiably vary that metaphor to -- architecture is frozen poetry. Both music and literature eschew clumsiness, banality, and cacophony and embrace matters such as theme, inventiveness, harmony, flow, smooth transition, felicitous repetition, appropriate language, and a sense of unity --the same qualities found in good architecture. The traits that make "Hamlet" a masterwork of literature are similar to those that make the Guaranty Building a masterwork of architecture.

Bemis and Butler Houses

But the question before the house today pertains to the former E. H. Butler dwelling at 429 Linwood Avenue, a little south of West Ferry. Was it designed by Joseph Lyman Silsbee (1848-1913) a significant architect who worked in Syracuse, Buffalo, and Chicago and was the first employer of Frank Lloyd Wright. Butler was the former publisher of the Buffalo Evening News.

Silsbee's only remaining documented architectural work in this area is the Bemis or Ransom mansion (1833) at 267 North Street across from College, in the Allentown Preservation District. The setting for the Junior League Show House two years ago, it is now back in the news as part of the real estate package purchased by or optioned to the P. J. Schmitt Co. for the proposed westward expansion of the Stuyvesant Plaza Bell's market.

The description of the exterior of the Bemis or Ransom house by architectural historian Frank Kowsky of State College in "Buffalo Architecture: A Guide" goes: "This house is perhaps the best work by Silsbee surviving in the city. Distinguished by inflated volumes, plunging roof lines, soaring chimney stacks, and aggressive ornament, the dwelling is typical of Silsbee's productions."

Now let us look at the original E. H. Butler house at 429 Linwood (1895). Can this also be the work of Silsbee or of his Buffalo architectural firm, Silsbee and Marling? The Linwood house has similar vaguely Richardsonian Romanesque qualities and similar dog gargoyles. To my knowledge, these are the only two structures in Western New York that have dogs on a high-pitched roof. The Linwood house has a slate roof rather than the red-tile of North Street. Both houses have stepped gables with gable ends, both have some round-headed Romanesque arches and Romanesque windows with voussoirs, both have bull's eye openings at the top of the main gable, both have steep roof lines and what Kowsky aptly describes as "aggressive ornament." In addition, both have Flemish Renaissance gable heads, the Butler house at the peek of the front gable, and the Bemis-Ransom house over the main entrance and over the side gables. Both have a main window stunningly decorated with leaded glass.

Did Frank Lloyd Wright adopt his famous use of leaded glass in his Prairie-style houses, such as the Buffalo ones, from Silsbee?

Finally, both houses have soaring chimneys and a corresponding perpendicularity. Their medieval decorative vocabularies are similar, and their statements and rhythms comparable.

Without knowing whether the interiors have undergone alterations and without considerable access to both buildings, one cannot compare their internal features. (However, see Bemis house interior photos that were taken in 2000.) However, one can speculate that Wright's partiality toward the inglenook may have derived from Silsbee. Every one of the five Wright houses in Buffalo has an inglenook, one of those, around-the-fireplace family centers. either built-in (as with the Barton house ) or planned to accommodate Wright-designed furniture (as with the Martin and Heath houses). Such a chimney corner is the main interior feature of the Bemis- Ransom house.

Is it fair to assume that Silsbee, or Silsbee and his Buffalo partner, James H. Marling (1857-1895), designed the former Butler home, built the year Marling died? Sadly, there is not yet any documentation. A search in the still uncatalogued and unindexed E. H. Butler papers in the E. H. Butler Library at State University College/Buffalo turned up nothing. The papers fail to show any correspondence with or records of any dealings with Silsbee or Marling, or anyone else, about 429 Linwood. The mystery, Watson, deepens.

Other sources, however, are yet to be tapped. Some possible ones may seep to the surface with the increased probing into Silsbee's work, the climbing recognition of his place in American architecture (See Buildings by Joseph Lyman Silsbee listed on the National Register of Historic Places), and his growing importance as the first employer and mentor of Frank Lloyd Wright. Aspects of his life may reveal yet other sources.

Silsbee Biography

Born in 1848, Silsbee was later graduated from Exeter and from Harvard. He followed H. H. Richardson at Harvard by about ten years, and H.H.R.'s Romanesque style was to become a major influence in his early career. Just out of college, Silsbee studied architecture at M. I. T. in 1870, the year its architectural school was founded, the first such school in the country.

In the course of the next few years Silsbee first worked for architectural firm in Boston and then traveled in Europe sketching architecture. Not long after returning from Europe, Silsbee moved to Syracuse, where he practiced architecture and was appointed professor of architecture at the new College of Fine Arts at Syracuse University. He designed in the city two fine, textbook examples of commercial Victorian Gothic, the huge Syracuse Savings Bank and the White Memorial Building, both still majestic landmarks of downtown Syracuse. The Syracuse Savings Bank was his first major commission, and on the strength of it, he married Anna Sedgwick, daughter of a prominent local banker. The success of these buildings brought him commissions for five residences in Syracuse, and he was offered the deanship of the new School of Architecture at Cornell, which he declined. Subsequently, he designed dwellings elsewhere in New York State, for example, in Ballston Spa, Albany, and Peekskill (in the latter place for Henry Ward Beecher).

In 1882 Silsbee opened an office in Buffalo with James H. Marling of Buffalo, but continued his office and residence in Syracuse. Although the firm designed a number of residences in Buffalo, the Bemis-Ransom house is the only known survivor.

In 1886 Silsbee moved to Chicago, where he formed a partnership with Edward A. Kent and where Frank Lloyd Wright worked for him. Kent, who had Buffalo connections, later practiced in Buffalo (the Unitarian Church at Elmwood and West Ferry, the Chemical 5 Firehouse on Cleveland, and the Douglas Cornell house on Delaware near Virginia). But he went down at sea in 1912 on the Titanic.

Although by 1897 Silsbee's prominence had begun to wane, he continued to practice in Chicago almost until the time of his death in 1913. His work divides into periods when he was designing in Gothic Revival, Richardsonian Romanesque, Queen Anne, Shingle, and Colonial Revival, all with a kind of textbook accuracy. He is also noted for having designed the Moving Sidewalk for the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, the forerunner of the moving platforms and escalators of today. But his greatest significance may rest on his influence on the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright.Silsbee could draw with amazing ease. He drew with soft, deep black lead-pencil strokes and he would make remarkable freehand sketches of that type of dwelling peculiarly his own at the time. His superior talent in design had made him respected in Chicago, His work was a picturesque combination of gable, turret and hip, with broad porches, quietly domestic and gracefully picturesque. A contrast to the awkward stupidities and brutalities of the period elsewhere. - F L. Wright, "An Autobiography"