F. L. Wright in Buffalo - Table of Contents ............ John Larkin - Table of Contents ..... Arts & Crafts in Buffalo - Table of Contents

![]()

F. L. Wright in

Buffalo - Table of Contents ............ John

Larkin - Table of Contents ..... Arts

& Crafts in Buffalo - Table of Contents

Frank

Lloyd Wright - Biography

TEXT Beneath

Illustrations

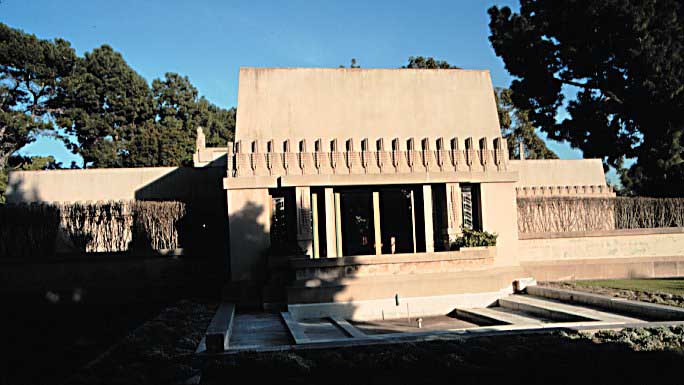

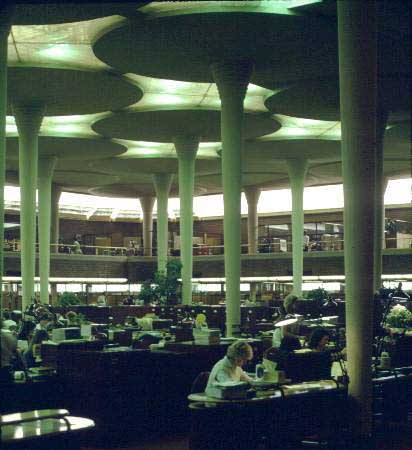

Unity Chapel  Louis Sullivan  Wright's home and studio in Oak Park  Walter Gale, "Bootleg" House, Oak Park, IL, 1893  Thomas Gale, "Bootleg" House, Oak Park, IL, 1893  Larkin Factory, Buffalo, NY  Unity Temple, Oak Park  Martin House, Buffalo  Robie House, Chicago  "Mamah" Cheney  Taliesin East, Wisconsin  Graycliff, Derby, NY  Barnsdall House, "Hollyhock House," Los Angeles, 1916-20  Fallingwater, Bear Run, Pa.  Johnson Wax Building  Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona  Joseph Mollica House, Milwaukee, WI, 1956  Guggenheim Museum, N.Y.C. |

|

Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin, to Anna Lloyd-Jones Wright, a teacher whose large Welsh family of farmers and ministers settled the valley that became Taliesin, and William Russell Cary Wright, a preacher and musician. An early influence was his clergyman father's playing of Bach and Beethoven. (Later on Wright would make comparisons to music and architecture in relation to the mathematical aspects of both.) Before her son was born, Anna had decided that her son was going to be a great architect. She placed pictures of buildings in his nursery and bedroom during his younger years to inspire him to become an architect. Using Froebel's geometric blocks to entertain and educate her son, young Frank was given free run of the playroom filled with paste, paper, and cardboard. Financial troubles plagued the William Wright family and eventually they would return to the support of the Lloyd-Jones clan in the hills of Wisconsin. Between 1878 and 1885, the family lived in Madison, but young Frank spent the summers on his Uncle James's farm near the Taliesin hill. He always considered the valley to be his home. "As a boy," he wrote in his autobiography, "I learned to know the ground plan of the region in every line and feature. For me now its elevation is the modeling of the hills, the weaving and fabric that clings to them, the look of it all in tender green or covered with snow or in full glow of summer that bursts into the glorious blaze of autumn. I still feel myself as much a part of it as the trees and birds and bees are, and the red barns." Wright's father and mother divorced in 1885 and Wright never saw his father again. Wright would later change his middle name to Lloyd. To help support the family, Wright worked for Allan Conover, a Dean of the University of Wisconsin's department of Engineering. Wright spent two semesters studying civil engineering at the University. In 1886, he executed the working drawings for the interior and helped with construction of Unity Chapel for his uncle Jenkin Lloyd Jones. The chapel was designed by architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee (a family friend). Wright then designed the original Hillside Home School for his aunts, Jennie and Ellen Lloyd Jones. In 1887, Wright moved to Chicago and took a job with Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Chicago during the late nineteenth century was an exciting place. The fire of 1871 destroyed most of the old city allowing for it to be rebuilt in the new industrial age. Skyscrapers were the all the rage in architecture, using steel and glass to create "shrines" piercing the sky. This complimented the trend in residential homes where Victorian influence created pointed gables, lace-like ornamentation, plaster walls, and wooden structures. The Adler and Sullivan Years: 1888-1893 A year later, 1888,

Wright moved to the well-known Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan firm as a draftsman where

he worked directly under Sullivan for six years. Sullivan was one of

the few influences Wright ever acknowledged. Wright picked up on the philosophy of Sullivan and was so loyally devoted to his employer that he soon moved ahead of Alder in importance within the firm. Sullivan was extremely critical of classicism which was appearing across the USA during the 1890's in reaction the 1893 Chicago World's Fair exhibits. Sullivan, known for his integrated ornamentation based on natural themes, developed the maxim "Form Follows Function" which Wright later revised to "Form and Function Are One." Sullivan also believed in an American architecture based on American themes not on tradition or European styles - an idea that Wright was later to develop. Wright's relationship with his employer caused great amounts of tension between Wright and fellow draftsmen, and well as in-between Sullivan and Alder. When Wright left the company, Sullivan's quantity of contracts declined quickly. Many years later, the two renewed their friendship. Wright often referred to Sullivan as his "Lieber Meister," or beloved master. Wright and Sullivan abruptly parted company in 1893 when Sullivan discovered that Wright had been accepting commissions for "bootleg" house designs on his own, a violation of an earlier agreement between the two. The moonlighting work showed the beginning of Wright's low, sheltering roof lines, the prominence of the central fireplace, and "the destruction of the box" open floor plans. Wright opened his own practice first in the Schiller Building in Chicago, then soon after in his home in Oak Park. The Oak Park Years: 1895-1909 In 1895, Wright expanded the living space of his home in Oak Park. During the marriage to Catherine, six children would be born. In 1898, he added a studio, a separate entity although connected to the house. The extraordinary home and studio complex -- now a museum (home page) -- served as Wright's architectural laboratory from 1889 to 1909, the years that launched his career. Here he conceived the Prairie style of architecture, testing ideas that found their fullest expression in many of the surrounding homes in Oak Park that he designed for clients. Many of his employees, including Barry Byrne, William Drummond, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahoney, also went on to significant architectural careers. From the studio complex, Wright designed more than 150 structures over the next decade. During this time, Wright developed a uniquely personal approach to residential design and imparted his principles to the architects who worked with him, ultimately fostering the Prairie School of Architecture. Wright took an integral approach to architecture by designing the interior furnishings of the building as well as the structure. He seemed to possess a skill of site memorization, and would visit the grounds sometimes only once before creating a building which blended with and complimented the site. Wright believed that architecture should create a natural link between mankind and his environment. "Organic architecture" as Wright came to call his work, should reflect the individual needs of the client, the nature of the site, and the native materials available. Some of Wright's most notable designs during this period were for "Prairie Houses." These houses reflected the long, low horizontal Prairie on which they sat. They had low pitched roofs, deep overhangs, no attics or basements, and generally long rows of casement windows that further emphasized the horizontal theme. He used native materials and the woodwork was stained, never painted, to bring out its natural beauty. This was his first effort at creating a new, indigenous American architecture. Other Chicago architects were also working in this same manner and the movement became known as "The Prairie School." Although Wright himself rejected that label, he became its chief practitioner. One of his most

famous

talks, "The Art and Craft of the Machine" was delivered in 1901 at Hull

House in Chicago. It marked the first decisive acceptance of the

machine by an American architect and was widely hailed. The Arts and

Crafts Movement, popular at the time, believed that much of the decline

in quality craftsmanship was directly attributable to the machine.

Wright, by contrast, embraced the machine and urged its use, not to

imitate fancy hand-carving, but to bring out the simplicity and beauty

of wood. This emphasis on simplicity and his insistence that natural

materials be treated naturally, was a hallmark of his work. Wright was associated with the Oak Park Unitarian Universalist congregation when they asked him to design a new church after their wooden church burned during a storm in 1905. The Unity Temple in Oak Park (home page) is one of the earliest public buildings constructed of concrete, poured in place into wooden molds. Wright was led to choose concrete because it was, in his words, "cheap," and yet could be made as dignified as more traditional masonry. His desire to create a house of worship expressing the powerful simplicity of ancient temples prompted his suggestion that it be called a "temple" rather than a church. In 1905 Wright traveled with his wife Catherine to Japan and began collecting and dealing in Japanese prints. 1903-06 Wright

designed

the Martin House in Buffalo,

New York (which introduced the horizontal bands of windows, a prominent

feature of his later houses). By 1907 he started to shock the Midwestern moral majority by flaunting married women in his grand, open car. Like a Secessionist "artiste," he let his hair grow over the collar. He wore expensive clothes, flowing neckties, riding breeches and Norfolk jacket - not the attire for the Oak Park commuter. He had reached the height of his Prairie School Style. Mamah Cheney In

1909

Wright moved his family into the studio and rented out the main part of

the house, and soon thereafter he left his family and practice in Oak

Park - accompanied by by his lover, Martha "Mamah" Borthwick

Cheney (the wife of one of his

clients). It was discovered that while in Europe, Wright and Mamah had

registered as Mr. and Mrs. Wright. Expectedly this caused a scandal in

the States. It was hard for Kitty (Catherine) to admit that the

marriage was over when Frank left for Europe. Kitty would not grant

Frank a divorce until 1923. Wright returned to Oak Park in 1910 (but not to his home and family), and the following year, he began building a new home and studio near Spring Green, Wisconsin. The complex, called Taliesin, was built on ancestral farmland. On Christmas Day, 1913, following Mrs. Cheney's divorce, he announced she would live with him at Taliesin. In 1914, Taliesin was set afire by Julian Carleton, a crazed servant who, newspapers reported, was underpaid and driven mad by the unconventional lovers. He started a fire during lunch, locked all the doors except for the lower half of a Dutch door, and as Mamah and each of her two children and four of Wright's leading workmen crawled out, he chopped off their heads. Although stunned by the tragedy, Wright began rebuilding Taliesin immediately, with completion in about a year. Following the completion of "Taliesin II," he met sculptress Maud Miriam Noel who joined him at Taliesin. He opened an office in Tokyo. Wright spent approximately six years (1916-22) working on Tokyo's Imperial Hotel, which was initially criticized for its aesthetic design, but when it survived a 1923 earthquake, which left the majority of Tokyo in rubble, it found praise. Wright had managed to design a "floating foundation" for the building which combined oriental simplicity, in modern world comfort. (The hotel was demolished in 1968; however, the entrance lobby was saved and was rebuilt at an architectural park near Nagoya, Japan.) Returning to the United States in 1922, .Wright opened an office in Los Angeles, California. where he pursued the use of a new material in residential homes: concrete. Most of these "textile block" houses were built in California with a Mayan and Japanese influence. In 1922, Wright was formally divorced from Catherine (who died in 1959, the same year that he died). In 1923, Wright's mother, Anna, died in February. He married Miriam Noel in November. Miriam's addiction to morphine is often thought to be the cause of bouts of maniac fantasy. She left Wright in 1924, less than one year after their marriage. Soon after Miriam Noel walked out on Wright, quite by chance, at a performance of the Petrograd Ballet, he met. Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg, daughter of Montenegro's Chief Justice and granddaughter of Duke Marko Milanov. In 1925, Wright started a practice in Chicago. In February, Olgivanna and her 8-year-old daughter moved into Taliesin. In April, a fire started by defective telephone wiring caused $250,000 - $500,000 worth of damage, and during the fire neighbors not only helped douse the flames, but helped themselves to some of Wright's oriental art, as well. He began construction of Taliesin III. In November, as a result of his living arrangement with Olgivanna, his wife Miriam began legal action. In December, daughter Iovanna was born to Wright and Olgivanna. In 1926, Olgivanna's former husband pursued custody of his daughter. Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the Mann Act and were arrested in Minnesota in October. The Bank of Wisconsin foreclosed on Taliesin. In 1927, a third fire at Taliesin caused loss of significant pieces of Asian artwork and damaged the studio. Part of the remaining Japanese art collection was auctioned in March to pay debts. The Bank of Wisconsin sold livestock at Taliesin in April and moved to take possession of the house. Miriam conceded to a divorce in August. Wright worked with some friends to regain Taliesin; as a result, "Wright, Incorporated" took legal ownership of Taliesin. Also in 1927, Graycliff, a summer home for Drawin Martin's family, was completed. In 1928, Wright Married Olgivanna, his third marriage. In 1932, at the age of 65, he published "An Autobiography" and "The Disappearing City" both of which influenced several generations of young architects. Usonian Wright's last "style," Usonian, was caused by a shift in society in the 1930's. Adapting architecture to the simple and economically tight lives of families in the 1930's, Wright used down scaling to bring the house to a more appropriate human level and reflect the informal and comfortable lives of the average American family. The Taliesin Fellowship During the Great Depression, with almost no architectural commissions coming his way, Wright and his wife Olgivanna founded an architectural apprenticeship program at Taliesin in 1932. The school was known as the "Taliesin Fellowship." It was, according to Wright and his wife, established to provide a total learning environment, integrating all aspects of the apprentices' lives in order to produce responsible, creative and cultured human beings, an idea comparable to that of a medieval manorial estate. Apprentices were to gain experience not only in architecture but also in construction, farming, gardening and cooking, and the study of nature, music, art and dance. Wright taught principles and philosophies of architecture, not a style. The Fellowship opened with thirty apprentices. During the thirties, Wright formed a social vision, associating the evils of society with the modern city. This was expressed through his design of Broadacre City, a section of an idealistic decentralized and restructured nation resembling not a city and not an agrarian community, but something in between. In 1935, Wright designed Fallingwater in Bear Run, Pennsylvania. In 1936, Wright designed S.C. Johnson & Son Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin. In 1937, Wright decided he wanted a more permanent winter residence in Arizona and he acquired several hundred acres of raw, rugged desert at the foothills of the McDowell Mountains in Scottsdale, Arizona. Here he and the Taliesin Fellowship began the construction of Taliesin West as a "Desert Camp" where they planned to live each winter to escape the harsh Wisconsin weather. "Taliesin West is a look over the rim of the world," in the architect's own words. It was a bold new endeavor for desert living. Taliesin West would serve as Wright's architectural laboratory for more than 20 years. There he tested design innovations, structural ideas, and building details. Taliesin West was for many years Wright's winter "camp" where he and his young apprentices took on the task of building their home, shop, school and studio, all the while responding to the dramatic desert setting. In 1943, Wright began the design for Guggenheim Museum in New York City. (He died during its construction, six months before the museum opened). Wright published "The Natural House" in 1954. This book discussed the Usonian home and a new concept called the "Usonian Automatic" - a house that could be owner built. His "Usonian" homes, which proved to be just as popular as his Prairie houses, were moderate-cost, single-story houses featuring such innovations as radiant heating (through hot water pipes placed in the cement slab floor); prefabricated walls made of boards and tar paper (a cheap and efficient building technique); an open plan with greater flow of space; and the invention of the carport. In 1959, Wright died at age 91 in Phoenix, Arizona. The Fellowship and their work continued under Olgivanna's leadership. Olgivanna died in 1985. The ashes of Olgivanna and Wright lie together at Taliesin West. Of the more than

1100

projects Wright had designed during his lifetime, nearly one-third were

created during the last decade of his life. So great is his fame that,

following his death, he was honored with his own U.S. postage stamp, as

well as a song, "So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright," written by the popular

musical duo, Simon and Garfunkel. Main sources:

|

| See also: Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape, 1922-1932 (online Nov. 2019) |