Dillon

Court House- Police & Fire Headquarters - Table of Contents

........................ Niagara

Square - Table of Contents

Michael J. Dillon U. S.

Court House / City of Buffalo Police and Fire Headquarters

68 Court St., Buffalo, NY

| Built: | 1936 |

| Architects: | Lawrence

Bley and Duane Lyman with Edward

B. Green and Son ("Bley" is pron. "Bley") |

| Style: | Art Deco Neoclassical Monumental Stripped Classicism, Starved Classicism—or PWA Modern |

| Michael J. Dillon |

IRS agent killed on duty |

| Vacancy: |

2011-2018 2011 Federal Courthouse on Niagara Square |

| Year

converted to the City of Buffalo Police and Fire Headquarters:

|

2018 |

| Status: |

2004 - Listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing element of the Joseph Ellicott Historic District in Buffalo |

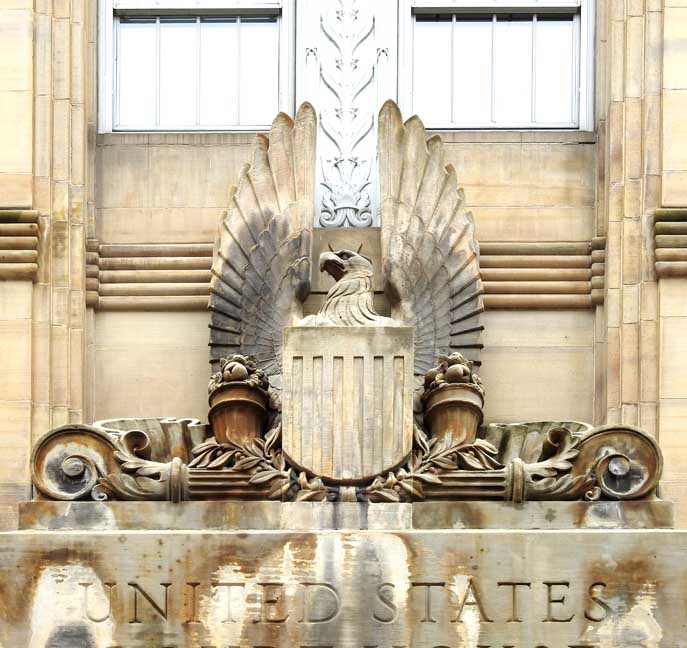

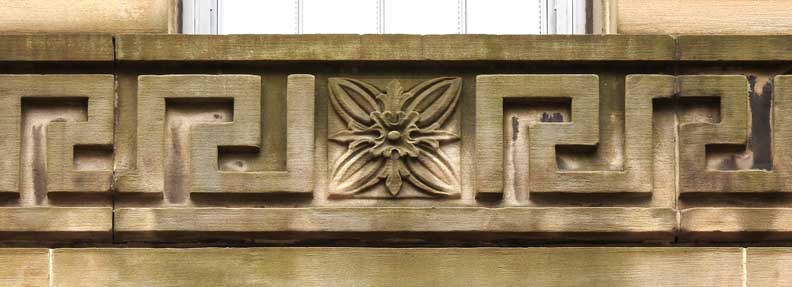

2002, 2019 photos Neoclassical Monumental style ... Details, starting near the top:  Art Dec stylized stone eagle flanked by stylized Ionic capitals  Fluted column shafts .... Cast aluminum spandrel panels and layered stringcourses detailed below:  Cast aluminum spandrel panel ... Egg-and-dart molding  Layered stringcourses  Main entrance  Dual a flanking paneled cartouche ... Horizontal dual staffs   Cf., the Federal seal on the US Courthouse at 2 Niagara Square Created by an Act of Congress on June 20, 1782 ... Shield … Bald eagle with its wings displayed … 13 arrows in left talon, (referring to the 13 original states) … Olive branch in its right talon depicted with 13 leaves and 13 olives, again representing the 13 original states … Eagle with head turned towards the olive branch, on its right side, said to symbolize a preference for peace… Scroll with the motto E pluribus unum ("Out of Many, One")… A "glory" with 13 mullets (stars) on a blue field forming a six-pointed star ... Flanking Roman fasces  Eagle standing on olive branch (peace symbol)  Linenfold at top center  Dentil molding  Greek keys  Art Deco light standard  Art Deco light standard ... Palm leaves  Pearl Street elevation |

|

Building History The monolithic U.S. Courthouse in Buffalo, renamed in 1987 in honor of longtime Internal Revenue Service employee Michael J. Dillon, occupies an entire block along Niagara Square, the city's civic center since 1802. Construction of the seven-story sandstone and steel courthouse in 1936 resulted from Buffalo's evolution as one of the country's most important industrial centers, which brought numerous federal agencies to the city. The courthouse concentrated the federal presence in an excellent example of the Art Moderne[?] architecture favored for government buildings funded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs. Federal government facilities had become so overcrowded by 1928 that the citizens of Buffalo pressured Congress for a new building to house all Federal offices in the city. The Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 authorized the construction of a number of federal buildings, including the Dillon Courthouse. Under the authority of the 1926 Public Buildings Act, the Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury Department was responsible for the design of all federal buildings. Due to economic pressures on small architectural firms during the Depression, local architects received some of these commissions. In January 1933, the Supervising Architect's Office retained two influential Buffalo firms, Green and Sons and Bley and Lyman, to prepare plans for the new U.S. Courthouse. Because of the unusual shape of the site, the architects created a pentagonal building. The courthouse is a unique example of Art Moderne[?] architecture because of its unusual shape and low-relief carved ornament. Originally planned as a twelve-story building, limited funding reduced its size to seven stories. President Roosevelt dedicated the courthouse on October 17, 1936 — his speech emphasizing the vital partnership between the Federal government and local officials in creating public works to overcome the devastating effects of the Depression. In 2004, the Dillon Courthouse was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing element of the Joseph Ellicott Historic District in Buffalo. Architecture The Michael J. Dillon U.S. Courthouse occupies an entire block bounded by Niagara Street, Niagara Square, Court Street, and Franklin Street. Located in the heart of the city, Niagara Square is surrounded by the Dillon Courthouse, the State Office Building, City Hall, and the City Court building. Resting on a granite base, the seven-story courthouse appears as a solid geometric mass of planar, yellow-gray sandstone walls and spare, carved detailing. Each elevation is divided into bays of vertical windows. The handsome carved detailing — emphasizing the building's horizontality — is concentrated at the entries, the first floor level, and building parapets. The fluted forms between the vertical strips of windows, on the other hand, resemble classical colonnades and provide a tension with the horizontality of the carved ornament. One of the two main entrances to the building, on Court Street, features a smooth stone surround into which is carved "United States Court House." A monumental carved eagle perches above the door surround. The entry doors, frames, and transoms are cast aluminum with ornamental grillwork. A cast-bronze medallion is centered above the middle door. Significant Events 1932: The Emergency Relief and Construction Act authorizes construction of several Federal buildings, including the courthouse in Buffalo. 1933: Two Buffalo architectural firms, Green and Sons, and Bley and Lyman, are retained to prepare plans for the U.S. Courthouse on Niagara Square. 1936: The cornerstone of the courthouse is laid and President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicates the building. 1987: The courthouse is named after Michael J. Dillon. 2004: The courthouse is nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing element of the Joseph Ellicott Historic District. Building Facts Architects: Green and Sons; Bley and Lyman Construction Date: 1936 Landmark Status: Contributing element in the Joseph Ellicott Historic District Location: 68 Court Street Architectural Style: Art Moderne[?] Primary Materials: Granite, yellow-gray sandstone, steel Prominent Features: Pentagonal footprint; carved sandstone ornamentation; aluminum details; main lobby and postal lobby; courtrooms |

The GSA article reprinted above contradicts the GSA article reprinted below in terms of style for the Dillon Courthouse: Art Moderne style above, but Stripped Classicism, Starved Classicism—or PWA Modern below. Construction for the building was completed in 1936, in general, the decade of Art Moderne style. The style of this building, however, - in my opinion - is not accurately described by Art Moderne. A better description would be "Stripped Classicism, Starved Classicism—or PWA Modern." Other style descriptions: Art Deco, or Neoclassical Monumental - Chuck LaChiusa, March 31, 2019 |

|

A Timeline of Architecture and Government Reprint:

GSA

(online April 2019)

1930

The Keyes-Elliott Bill, an amendment to the Public Buildings Act of 1926, passes. The bill provides the secretary of the Treasury increased authority for entering into service contracts with private architects. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) begins a concerted lobbying effort for the Office of the Supervising Architect to reorganize as a management organization and cease its federal building design responsibilities. The AIA’s campaign is largely unsuccessful, as the government retains design responsibility for the smaller projects, awarding only larger commissions to private firms. Late 1920s-Early 1930s  The Joel Solomon Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, Chattanooga, Tennessee Photo credit: Carol M. Highsmith Private

sector begins to embrace modern architectural ideals and new building

technologies. Examples include Rockefeller Center (Associated

Architects) in New York City and the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society

building (Howe and Lescaze) in Philadelphia.

During the 1930s, the government embarks on a prolific construction program, and federal buildings throughout the country are planned and executed. Many buildings continue to reflect traditional styles, though they increasingly bear the influences of the early modern movement. Used primarily for government architecture, a new architectural style emerges that effectively straddles classicism and modernism. Simplified neoclassical forms are paired with the stylized designs of the Art Deco style. This new public building style is today alternately known as Stripped Classicism, Starved Classicism—or PWA Modern in recognition of the Public Works Administration that oversaw many such designs. |

|

Partial reprint

JUDGE TO FREE AILING KILLER OF IRS AGENT By Matt Gryta The Buffalo News, April 25, 1997 (online May 2019) A judge today spared James F. Bradley, 77, further prison time for the only murder of an on-duty Internal Revenue Service agent in government history. State Supreme Court Justice Mario J. Rossetti told the seemingly repentant Bradley, who has been hospitalized for the past year, that he was taking into account Bradley's worsening "physical incapacities" and the time he has spent in custody in not reimposing a 20-year prison term on him. Bradley, a former IRS agent, has spent 13 1/2 years in custody since he fatally shot agent Michael J. Dillon, 61, of Batavia three times during a confrontation in the kitchen of Bradley's Cheektowaga home on Sept. 23, 1983. Rossetti ordered Bradley to begin making a total of $5,000 in reparation payments beginning in June to Evelyn Dillon, the victim's widow. As Bradley left the courtroom, he said, "Well, I'm glad to be alive." Inside the courtroom, Mrs. Dillon asked the judge to reimpose the 20-year term Bradley got 12 years ago for what she called his "cowardly act." But Mrs. Dillon also told the judge she would agree to his considering a lesser sentence if Bradley "expressed sincere remorse" for the slaying. Bradley told the judge he feels remorse for Mrs. Dillon. Bradley also contended "Uncle Sam made me" a killer in World War II and that Dillon "wasn't even in the picture" when he shot him. Bradley suggested to the judge that the killing of Dillon was his way of getting back at the IRS, which he said had "persecuted him" for leaving government service in a pay dispute decades ago. Outside the courtroom, Mrs. Dillon declined to comment, and Bradley's attorney, Terrence M. Connors, and Bradley's son, Kevin, said Bradley will live with his son and his family in North Carolina and see some of his six grandchildren for the first time. On March 6, Bradley pleaded guilty to first-degree manslaughter after months of plea talks with the Erie County district attorney's office. Originally indicted on murder in the case and convicted of first-degree manslaughter in a 1985 Buffalo jury trial, Bradley saw his conviction and 6 2/3 -to-20-year prison term overturned last year on legal technicalities. Dillon was killed in Bradley's South Huxley Drive home while pressing him, under orders from superiors, to surrender a family car to cover the remaining $332 debt on a $2,000 tax lien he had been repaying over two years. |