St. Peter's Basilica - Table of Contents .............. Architecture Around the World

2002

photos

Exterior - St. Peter's Basilica

Vatican

City, Italy

TEXT Beneath Illustrations

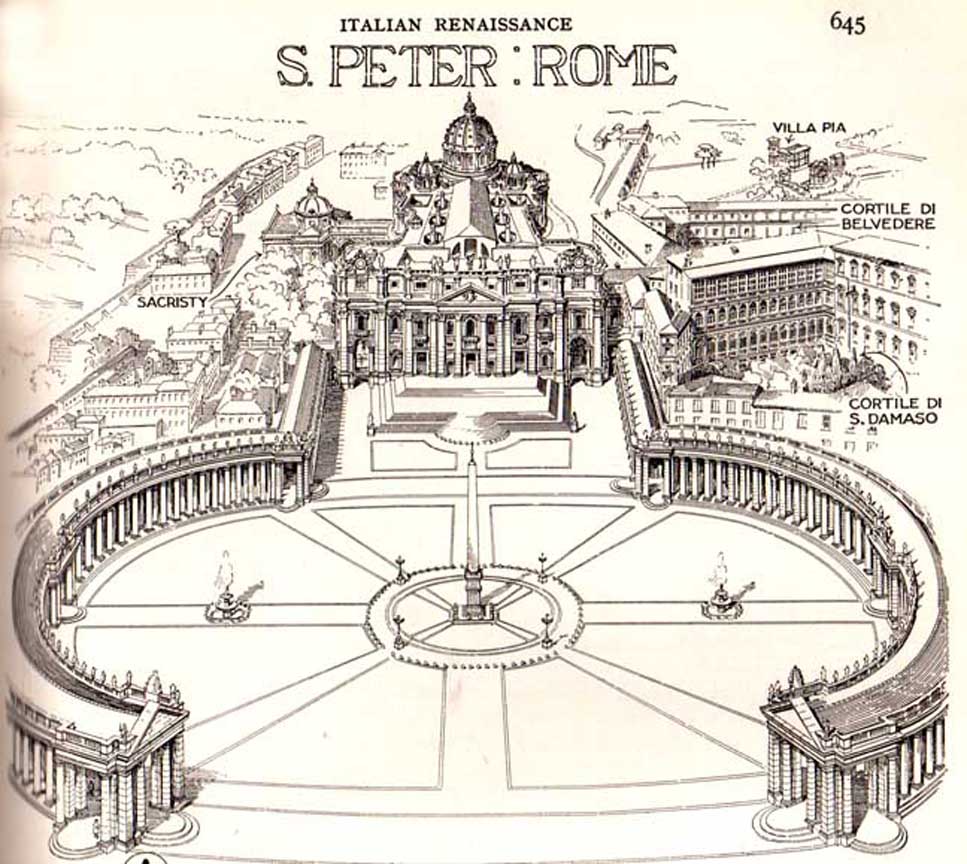

Drawing source: A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, by Sir Banister-Fletcher, New York, 1950, p. 645. St. Peter's Square, by Bernini Colonnade Corinthian capital Wrought iron scroll acanthus leaf sconce arm ... Travertine |

Michelangelo's cupola Top: Finial atop the lantern ... Middle: Copper cupola ... Bottom: Drum Copper cupola Papal symbols atop clock |

Facts about St. Peter's Basilica:

- Replaced an earlier St. Peter's Basilica built by Constantine in 323 A.D. which was built supposedly over the tomb of St. Peter

- The 1506 building was designed for Pope Julius II by Bramante (after Bramante's death, Raphael, then to Baldassarre Peruzzi, later to Antonio da Sangello the Younger, and then to Michelangelo

- Michelangelo returned in part to to Bramante's plan and built a basilica in the form of a Greek cross with 5 cupolas, the largest of which is the huge central cupola

- In the 17th c., Carlo Manderno revised the shape into a Latin cross

- St. Peter's Square was built by Bernini 1656-1667.

- 2 huge semicircles; 280 columns, surmounted by 160 statues of saints

- Middle of square has Egyptian obelisk from Circus of Caligula and Nero

- Twin fountains in the square, the one on the right by Maderno and the other by Bernini

Although Baroque architecture was to spread all over Europe, it was born in Rome and its founding father was Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). This precocious sculptor was selling his work at age sixteen to the Borghese family. By twenty, Bernini was so famous, the pope commissioned him to sculpt a papal portrait. Not content to excel in the plastic arts, Bernini was the greatest scene designer of the age. When he created a stage set, the illusion was so convincing, people in the front row fled in terror, convinced they would be drenched by flood or scorched by fire.

Bursting with talent doesn't begin to describe Bernini's abilities, for he was also an esteemed painter, poet, and composer. An English visitor recalled attending an opera in 1644 where Bernini "painted the scenes, cut the statues, invented the engines, composed the music, wrote the comedy and built the theater. " If they had had popcorn, Bernini would have popped and buttered it.

In 1623, Bernini began his career as an architect. For the next fifty years, his fingerprints were all over Rome. His vision, skill, personality, and art shaped the grandeur, flamboyance, and emotionalism of Counter-Reformation Vatican City, and of the Baroque era in general.

Piazza San Pietro (St. Peter's Square)The best example of Bernini's larger-than-life work is the piazza outside St. Peter's Basilica. Bernini conceived the piazza (1656-67) as an enormous oval framed by two colonnades of 284 columns and 88 pillars in four rows. Topped by an entablature with 140 statues of saints, the curved colonnades embrace a 650-foot-long oval like "the motherly arms of the church," as Bernini said.

Although composed of miscellaneous elements, the composition coalesces around a central obelisk originally brought to Rome by Caligula (it served as a turning point in Nero's Circus Maximus). Paving stones between two fountains and the obelisk indicate viewing points from which each wing of the colonnade seems to have only one row of columns rather than four abreast. Out of the vast scale and variety of elements, Bernini created a unified effect for visitors' first glimpse of St. Peter's.Michelangelo

Among Michelangelo's difficulties had been his struggle to preserve and carry through Bramante's original plan, which he praised even as he changed it. With Bramante's plan for St. Peter's, Michelangelo managed a major concentration, reducing the central fabric from a number of interlocking crosses to a compact, domed Greek cross inscribed in a square and fronted with a double-columned portico. Without destroying the centralizing features of Bramante's plan, Michelangelo, with a few strokes of the pen, converted its snowflake complexity

into massive, cohesive unity.

The same striving for a unified and cohesive design is visible in Michelangelo's treatment of the building's exterior. Later changes to the front of the church make the west (apse) end the best place to see his style and intention. The colossal order again serves him nobly, as the giant pilasters march around the undulating wall surfaces, confining the movement without interrupting it. The architectural sculpturing here extends up from the ground through the attic stories and moves on into the drum and the dome, pulling the whole building together into a unity from base to summit. Baroque architects will learn much from this kind of integral design, which ultimately is based on Michelangelo's conviction that architecture is one with the organic beauty of the human form.The domed west end - as majestic as it is today and as influential as it has been on architecture throughout the centuries - is not quite as it was intended to be. Originally, Michelangelo had planned a dome with an ogival section (raised silhouette), like that of Florence Cathedral. But in his final version he decided on a hemispheric (semicircular silhouette) dome to moderate the verticality of the design of the lower stories and to establish a balance between dynamic and static elements.

However, when Giacomo Della Porta (c. 1537-1602) executed the dome after Michelangelo's death, he restored the earlier high design, ignoring Michelangelo's later version. Giacomo's reasons were probably the same ones that had impelled Brunelleschi to use an ogival section for his Florentine dome greater stability and ease of construction The result is that the dome seems to be rising from its base, rather than resting firmly on it - an effect that Michelangelo might not have approved. Nevertheless, the dome of St. Peter's is probably the most impressive and beautiful in the world and has served as a model for generations of architects to this day.

Sources:

- "The Annotated Arch," by Carole Strickland. Pub. by Andrews McMeel, 2001

- "Gardner's Art Through the Ages, Tenth Edition," by Richard G. Tansey and Fred S. Kleiner. Harcourt Brace College Pub.1996.

- "An Outline of European Architecture," by Nikolaus Pevsner. Pelican Books, 1975.

- Leonardo B. Dal Maso, "Rome: From the Palatino to the Vaticano." 1992.