Partial reprint

Buffalo

factories

were key battlegrounds in early 'Ford vs Chevy' tilt

·

By Steve Cichon

The

Buffalo News. Sep 30, 2020

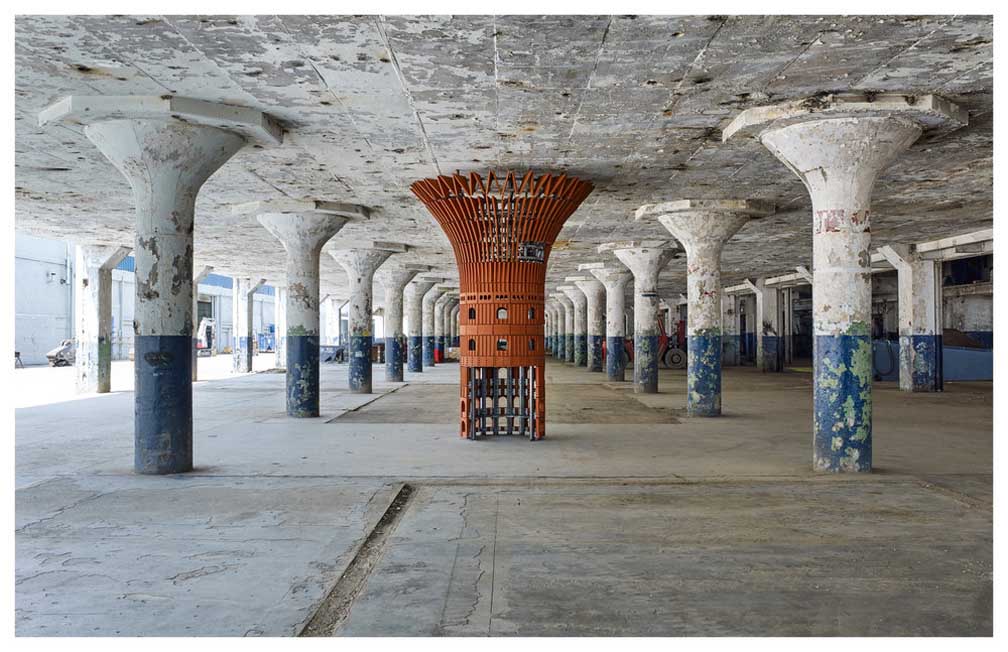

1922 photo

There

have been volumes

written about the famous Buffalo-built cars like the Pierce-Arrow,

the Thomas

Flyer, and even the postwar two-seater the Playboy.

And those names are only

the tip of the iceberg. Dozens of different makes and models

were built in Buffalo,

especially in the early decades of automotive history.

While

the

names Ford

and Chevrolet don’t instantly bring Buffalo to mind, it is in

the early stories of both of those lions of American industry

that Western New

York and Western New Yorkers have made the greatest impact in

the history of

motoring.

Millions

and

millions of Fords and Chevys were built in Buffalo by

thousands of our

blue-collar fathers and grandfathers – but it wouldn’t

have happened

without the Danish immigrant who quit his job with the

railroad to come to

Buffalo as a bicycle mechanic.

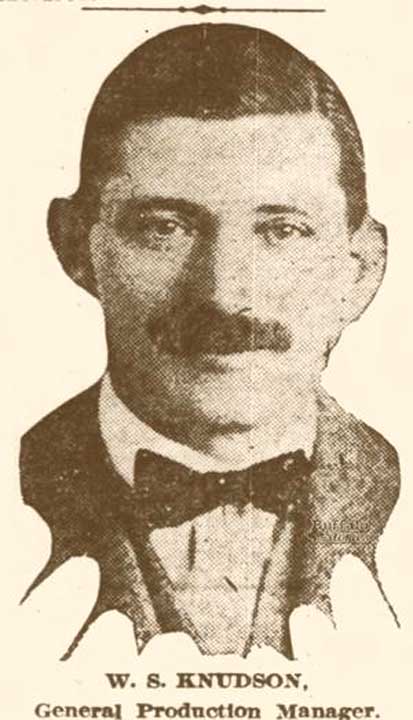

William

S.

Knudsen would eventually become president of General

Motors and was

President Roosevelt’s point man for war supply production

during World War

II.

But in 1906, Knudsen was living on Victoria Avenue, a few blocks from

the John R. Keim factories on Kensington Avenue at Clyde

Avenue. He worked at

the factory that produced machined metal parts – first for

bicycles, then more

and more for automobiles. As Keim became one of Ford’s leading

suppliers for

axle housings and drip pans, Henry Ford visited Buffalo in

1910 to buy out the

factory.

Knudsen became one of Ford’s trusted

lieutenants, and was the superintendent of the factory that

became Buffalo’s

first large-scale auto assembly plant. Before moving to

Detroit to serve in a

corporate capacity with Ford, Knudsen oversaw the building of

the new Ford

plant

on Main Street in 1915. More than 600,000 Model-T Fords

were churned out

of the factory which, after years as a Bell

Aircraft and Trico factory, still

stands today as the Tri-Main

Building.

Henry

Ford

called Knudsen “the greatest production genius in modern

time.”

In

1930,

Ford purchased a submerged plot of land on Fuhrmann

Boulevard, and after

backfilling more than 30 acres of land, a new Ford assembly

plant was built.

Between 1931 and the plant’s closure in 1958, about 2 million

Buffalo-built

Fords rolled off the line. The building still stands along

Buffalo’s Outer

Harbor as “Port

Terminal A.”

Meanwhile, after running Ford’s entire 27-plant production system after

the end of World War I, Knudsen left Ford in a disagreement,

eventually moving

to GM with a chip on his shoulder. As a vice president at Chevrolet,

his

Danish-accented, one-line speech to workers became famou

“I vant vun for vun” was printed that way in

employee newsletters, and it was a bold challenge. He wanted

one Chevy built

for every Ford built. It was a huge dream – at the time, Ford

was clearly at

the top, while Chevy was America’s seventh-most popular car.

Among

Knudsen’s

first bold strokes in chasing Ford was to return to his

adopted

hometown of Buffalo to build a 600,000 square-foot, $2.5

milllion Chevy

assembly and body plant on East

Delavan Avenue.

The

first

Chevys built in Buffalo hit the roads in summer 1923, and soon

the

factory was making 8,000 cars per month. The same “genius”

level production

mind that gave Henry Ford his first million car year helped

transform, almost

overnight, Chevrolet from an also-ran to the company that

would be Ford’s

greatest domestic competitor for almost a century and

counting.

The Buffalo plant was a major player in Chevy’s surge to become

America’s second-most popular automobile. After 18 years and

well over a

million vehicles, in 1941 the plant was converted to defense

production

After the war, the facility was refitted into

an axle, brake and clutch factory. GM eventually spun off

American Axle, which

continued operating the plant until 2007. Efforts to remediate

parts of the

property for redevelopment have been ongoing since the plant’s

closure

While it’s been generations since Buffalo has rolled completed cars off

of assembly lines, there are still about 1,400 GM workers

creating components

at the former Harrison Radiator in Lockport. GM’s Tonawanda

Engine plant was

opened in 1938 and employs about 1,600 workers. Opened in

1950, the Ford

Stamping Plant in Hamburg continues to employ around 1,200

And Buffalo’s link to the earliest days of

the “Ford vs. Chevy” battle lives on.

|