Last

October, Karen Little, executive director of the Maria [pronounced

mar-EYE ah] Love Convalescent Fund and author of "Maria Love, The Life

and Legacy of a Social Work Pioneer," told a gathering of some four

score people gathered at the Wilcox Mansion of the history of Ms. Love

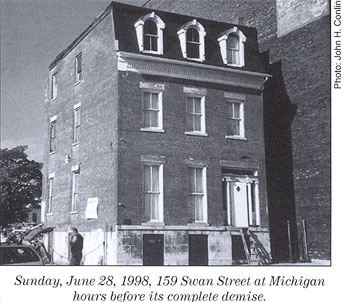

and the "crèche" she founded. The original building housing the crèche,

at 159 Swan Street, is the subject of a demolition request by the

current owner [Ed. note: the building was subsequently demolished].

That has spurred community interest.

The lecture was sponsored by the Preservation Coalition and the

Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site.

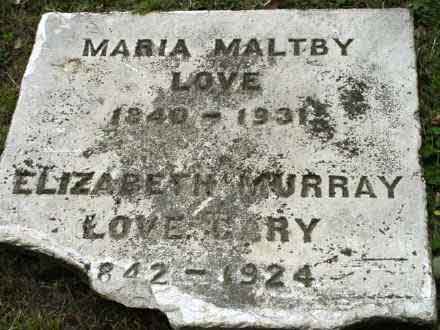

Mrs. Little established the social context Maria Love (1840-1931) grew

up in, a context marked by personal economic instability amidst pell

mell industrial and commercial growth.

Economic background

19th Century America

-- and Buffalo -- was marked by heated periods of growth and

speculation and equally spectacular economic catastrophes. Despite

severe panics in 1832, 1834 and 1849, the city kept growing. The growth

attracted poor natives and immigrants alike. These groups often fell

prey to all manner of swindlers, both in transit and once they arrived

in Buffalo. Menial jobs on the canal and waterfront kept wages low.

The Civil War era brought rising prices, swelling the ranks of the

poor. The war also brought disabled soldiers and widowed and orphaned

children. Financial panics hit in 1873 and 1877.

By the 1870's a moral response, the Social Gospel Movement, had taken

hold among many of the wealthier Buffalo churches such as St. Paul's

Episcopal, Trinity Episcopal, Westminster Presbyterian, and First

Presbyterian. The movement preached responsibility for the poor and

involvement in government and civic reform. Maria Love was a member of

Trinity Episcopal [Ed. note: There is a room named after Ms. Love in the church administration building].

The City had a Poor Department, which dispensed groceries, fuel,

clothing, rent, cash allowances and burial expenses to needy families.

This was collectively referred to as "outdoor relief." In 1877

one out of seven was believed to receive some form of outdoor relief.

The amount spent had tripled from 1864 to 1876, but the reformers

believed that much of it was wasted on fraud and that it encouraged

dependence, leading to pauperization. The administering of alms to the

poor, or charity, was targeted by the Buffalo reformers.

.......

....... Newspaper clippings

Newspaper clippings