Buffalo

Grain Elevator Preserve - Table

of Contents

.....

Types

of Bridges in Buffalo ..........

Waterfront - Table of Contents....

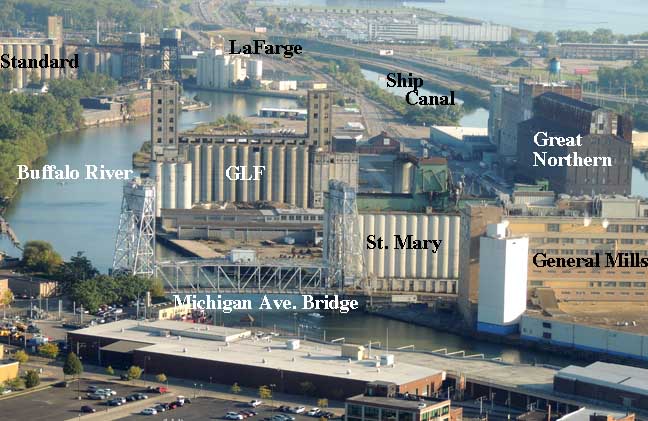

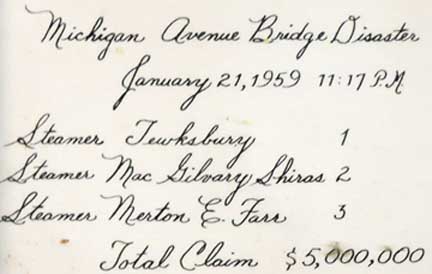

Michigan Avenue Bridges

including the Tewksbury Incident

Michigan Avenue Bridge AKA:

Michigan Avenue NORTH Bridge

On this page, below:

Michigan Avenue (North) Bridges: |

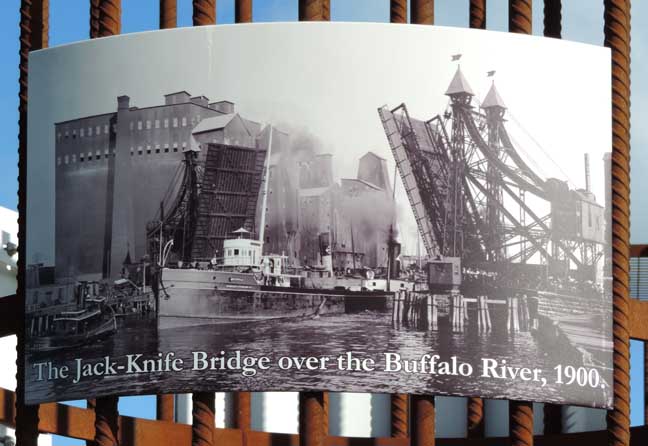

| Jack-Knife

Bascule Bridge 1897-1929  1897-1929 Jack-Knife Bridge Bascule bridge Historic Photos 1894-1941, Industrial Heritage Trail Signage  1897-1929 Jack-Knife Bascule Bridge Postcard  1897-1929 Jack-Knife Bascule Bridge City Elevators on left, Kellogg Elevators on right. Library of Congress (online October 2020) |

1959

Tewksbury Incident After the Tewksbury disaster ... Details below: Photo courtesy of the Swannie House restaurant  Note mangled bridge remains next to the Tewksbury Photo courtesy of the Swannie House restaurant  Note mangled bridge remains next to the Tewksbury ... The Shiras is next to the "Tewksbury" Photo courtesy of the Swannie House restaurant  Photo courtesy of the Swannie House restaurant |

|

Reprint Torn-Down Tuesday: The Michael K. Tewksbury topples the Michigan Avenue Bridge By

Todd Hariaczyi

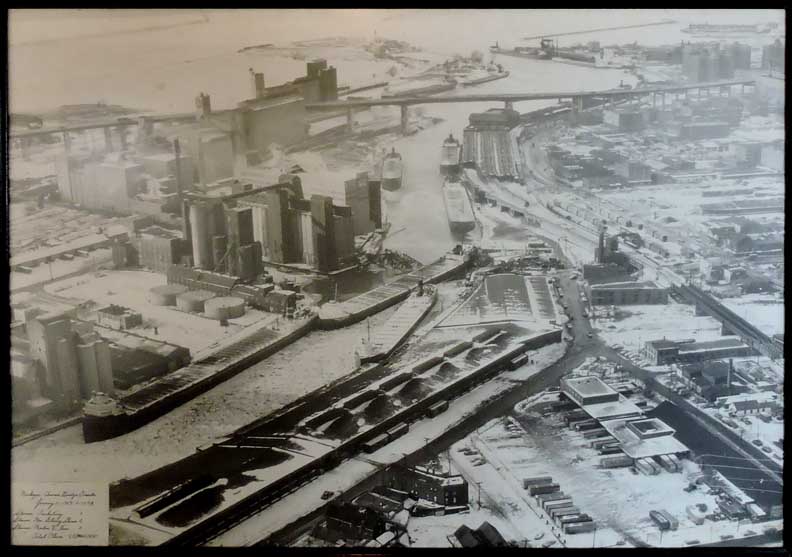

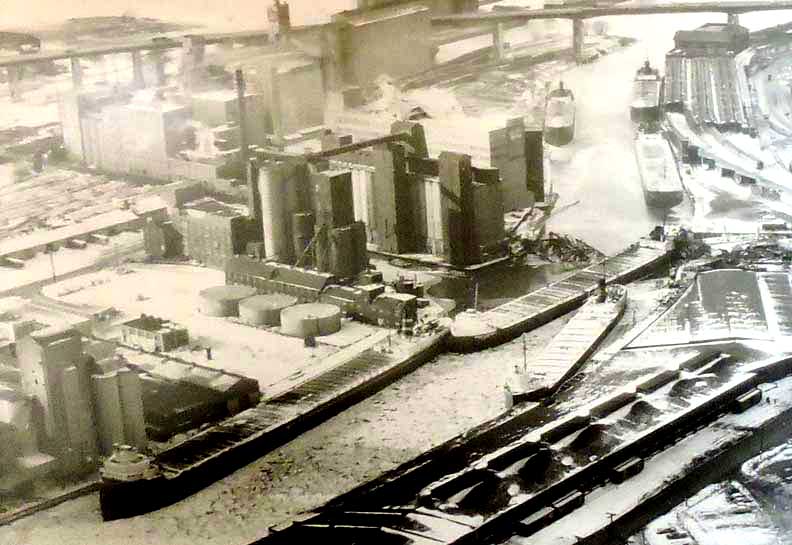

Published July 4, 2017 The Buffalo News  The Edward M. Cotter fireboat tends to the runaway Michael K. Tewksbury and the collapsed Michigan Avenue Bridge. (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo History Museum) Buffalo's most famous – or infamous – season has long been the butt of jokes, largely on account of that pesky Blizzard of '77. Of course, one season of falling snow, frigid temperatures and high winds should not define a city – Buffalo has a lifetime of that season, to her credit – but winter did contribute to one of the costliest disasters in the city's history on Jan. 21, 1959. Toss in a pair of thirsty crewmen, a philandering watchman and a runaway ship whose length would dwarf a football field, and you have yourself the so-called Tewksbury Incident.  An aerial view of the Buffalo River shows the two runaway freighters and the collapsed Michigan Avenue Bridge. (Photo courtesy of the Buffalo History Museum) The winter of that year had been exceptionally cruel, defined by heavy snow, bitter temperatures and blowing winds, but on Jan. 21, there was an unseasonable thaw that broke up the sheet of ice along Cazenovia Creek, pushing it toward the Buffalo River. Down river, the ice jam barreled into the hull of the freighter MacGilvray Shiras, which was moored for the winter at the Concrete Central Elevator near the foot of Smith Street. Its moorings splintered and, propelled by the ice jam behind it, the unmanned freighter, incredibly, deftly maneuvered the corners of the meandering Buffalo River until it came to the Michael K. Tewksbury. The MacGilvray Shiras plowed into the Tewksbury, wrecking that freighter's moorings. Together, the two unmanned freighters raced under the Ohio Street Bridge, which was raised for the winter. The Michigan Avenue Bridge did not fare as well, unfortunately, as the Michael K. Tewksbury crashed into it, and the bridge fell into a tangled heap of steel atop the resting freighter. The worst was yet to come, however, as the frigid waters of the Buffalo River backed up and poured into 18 blocks of the Old First Ward throughout the night. Weather could not solely be blamed for the disaster. A boat watchman for the Michael K. Tewksbury had left his post to visit his mistress. A pair of bridge crewmen had left their posts at the Michigan Avenue Bridge to indulge in drink at the nearby Swanee House.  Michael K.

Tewksbury, president of the Midland Steamship Lines, surveys the damage

to the ship bearing his name following the accident. (Photo courtesy of

the Buffalo History Museum)

Ultimately,

it was the Kinsman Marine Transit

Co., owner of the MacGilvray Shiras, that bore responsibility for

failing to securely moor the freighter. Damages to the bridge and

neighboring properties surpassed $6 million, but other than some minor

injuries sustained by the pair of bridge crewmen who hurried back from

the tavern in a desperate attempt to raise the bridge, no one was hurt

in the Tewksbury Incident.

|

|

Excerpts Tewksbury Incident to be remembered Saturday in South Buffalo's River Fest Park By Anne Neville The Buffalo News, September 5, 2013 It isn't mid-January, but the images of a solid wall of storm-powered ice that shoved a massive lake freighter into the Michigan Avenue lift bridge, destroying it and causing a huge flood of icy water into homes in South Buffalo, the Old First Ward and the Valley, will be on everyone's minds Saturday. A program of story, songs and displays called “Ghost Ships and the Flood: Remembering the Tewksbury Incident” will commemorate the community-wide crisis that happened on Jan. 21, 1959. The Tewksbury Incident remains an unforgettable event to those who lived through it on Jan. 21, 1959. After days of extreme cold and heavy snow packed the Buffalo River and Cazenovia Creek with ice, a sudden thaw and wind-driven rain on Jan. 21 broke up the ice, and about 10 p.m. the pressure of the shifting floes snapped the mooring lines of the freighter MacGilvray Shiras, which was tied up for the winter beside the Concrete Central Elevator [Continental Grain elevators] at the foot of Smith Street. The MacGilvray Shiras, the length of a football field, drifted downriver, somehow navigating the sharp turn opposite Smith Street before ramming the Michael K. Tewksbury, which was tied up at the Standard Elevator, near the foot of St. Clair Street. Both boats passed beneath the Ohio Street bridge, which was raised for the winter, but the bridge crew, taking a break in the Swannie House, could not raise the Michigan Avenue bridge in time. The Tewksbury smashed into the bridge at 11:17 p.m., demolishing it, and wedging itself across the river. The flow of frigid water and ice spilled into the neighborhood, flooding an 18-block area. It took years for the Tewksbury case to work its way through the courts, with plenty of lawsuits filed and finger-pointing. Besides the two bridge-keepers who had to scramble from the Swannie House to the bridge in an attempt to raise it, investigators found that the Tewksbury's watchman was away from his post and on shore with a lady friend when the freighter broke free. At the event in 2009, Overdorf said, a “little lady came in and told her, “‘You know the guy who was supposed to be tending the boat that broke loose? That was my husband! He was up on land with the girlfriend!' It was 50 years later, and she was as bitter as she must have been when she found out. She said she couldn't stay, and she walked out. I never got her name, and I have no idea who she was.” |

|

On the brisk night of January 21st, 1959, members of the Michigan Avenue bridge crew also came to find out how the end of an ordinary work day could turn into anything but ordinary in a matter of seconds. The MacGilvray Shiras, one of many great lakes freighters routinely moored up for the winter, patiently waited the annual thawing of the waterways. Owned by The Kinsman Marine Transit Company (which is, yes, owned by the Steinbrenner family), Shiras sat in the Buffalo River by the Continental Grain elevators at the base of Smith Street just like any other night. The clock approached 11 P.M. as the Michigan Avenue bridge crew allegedly finished up their drinks at the nearby Swannie House, one of the oldest taverns in Buffalo (Est. 1886 and still serving). There was a staff shift to take place on the hour. Whether it be a significant other, an entire family, or even something as humble as a bed to rest their backs on after a long day's work, it can be assumed that these men were looking forward to getting off work and going home. The roots of St. Clair Street moored another freight, named The Michael K. Tewksbury. For the owner of the ship, as well as the men about to get off work, it was just like any other night: the freights were unmanned, the river was tranquil, and anyone with a financial stake in the freighting industry could not ask for the ice to melt any quicker. Three miles from the Shiras, five miles from the Tewksbury, six miles from the bridge, an ice jam in Cazenovia Creek broke loose, literally dumping excess water and fragmented ice right out into the Buffalo River. First, the Shiras. This massive influx of everything cold had its way with the freight upon impact, causing the ship to “dead-man.” In old Irish sea terminology, this commonly refers to the wires and cables securing anything from the masts to, in this case, the vessel itself coming undone. Back when thick ropes where implored, you could picture the ensuing chaos of one of the main masts starting to collapse, giving the term “dead-man” some validity (because if the crew did survive, whoever's poor skills where behind the lazily secured ropes and cables were as good as dead). Alas, this is not the time of the explorers such as Columbus; we use extremely high-tension cables. And, just like those ropes that held up those masts, these came undone. They flailed through the cold Buffalo night air by no one's will other than physics, one after another. Each powerful whiplash of freshly snapped high-tension wire allowed the monster to descend that much faster down the river. Next was the Tewksbury. Shiras hit her just right, merely uprooting her and taking her with him. The sound of the collision was the gunshot that commenced the head-to-head race between the two freights to the Michigan Avenue Bridge. Word finally began to spread about these unmanned ships careening down the Buffalo River and local authorities were notified. Naturally, Mother Nature already plotted the ship's trajectory; the only thing anyone could do was make sure that nothing was in its path. The Buffalo Fire Department called the bridge station to inform them that they needed to raise it. The phone rang but to no avail as the staff was finishing up their drinks across the street. When efforts were finally made to try to raise the bridge it was just too late. Shortly after 11 P.M. the two freights collided head on with the structure, causing a pile up of gargantuan proportions. Two banged up ships, both over 400 feet long, and the remains of a bridge now sat in a channel roughly 175 feet long. The water and ice quickly overcame this accidental dam and proceeded to flood out the entire historic “Old First Ward District.” Thankfully there were no casualties. |

Partial Reprint Petitions of the Kinsman Transit Company, As Owner and Operator of the Steamer Macgilvray Shiras, Appellant, and Of Midland Steamship Line, Inc., As Owner and Operator of the Steamer Michael K. Tewksbury, Their Engines, Etc., Appellee,for Exoneration from or Limitation of Liability, city of Buffalo, Claimant-respondent-appellant, kelley Island New York Corporation, et al., Claimants-appellees, 338 F.2d 708 (2d Cir. 1964) Pub. on Justia (online July 2017) The Buffalo River flows through Buffalo from east to west, with many turns and bends, until it empties into Lake Erie. Its navigable western portion is lined with docks, grain elevators, and industrial installations; during the winter, lake vessels tie up there pending resumption of navigation on the Great Lakes, without power and with only a shipkeeper aboard. About a mile from the mouth, the City of Buffalo maintains a lift bridge at Michigan Avenue. Thaws and rain frequently cause freshets to develop in the upper part of the river and its tributary, Cazenovia Creek; currents then range up to fifteen miles an hour and propel broken ice down the river, which sometimes overflows its banks. On January 21, 1959, rain and thaw followed a period of freezing weather. The United States Weather Bureau issued appropriate warnings which were published and broadcast. Around 6 P.M. an ice jam that had formed in Cazenovia Creek disintegrated. Another ice jam formed just west of the junction of the creek and the river; it broke loose around 9 P.M. The MacGilvray Shiras, owned by The Kinsman Transit Company, was moored at the dock of the Concrete Elevator, operated by Continental Grain Company, on the south side of the river about three miles upstream of the Michigan Avenue Bridge. She was loaded with grain owned by Continental. The berth, east of the main portion of the dock, was exposed in the sense that about 150' of the Shiras' forward end, pointing upstream, and 70' of her stern — a total of over half her length — projected beyond the dock. This left between her stem and the bank a space of water seventy-five feet wide where the ice and other debris could float in and accumulate. The position was the more hazardous in that the berth was just below a bend in the river, and the Shiras was on the inner bank. None of her anchors had been put out. From about 10 P.M. large chunks of ice and debris began to pile up between the Shiras' starboard bow and the bank; the pressure exerted by this mass on her starboard bow was augmented by the force of the current and of floating ice against her port quarter. The mooring lines began to part, and a "deadman," to which the No. 1 mooring cable had been attached, pulled out of the ground — the judge finding that it had not been properly constructed or inspected. About 10:40 P.M. the stern lines parted, and the Shiras drifted into the current. During the previous forty minutes, the shipkeeper took no action to ready the anchors by releasing the devil's claws; when he sought to drop them after the Shiras broke loose, he released the compressors with the claws still hooked in the chain so that the anchors jammed and could no longer be dropped. The trial judge reasonably found that if the anchors had dropped at that time, the Shiras would probably have fetched up at the hairpin bend just below the Concrete Elevator, and that in any case they would considerably have slowed her progress, the significance of which will shortly appear. Careening stern first down the S-shaped river, the Shiras, at about 11 P.M., struck the bow of the Michael K. Tewksbury, owned by Midland Steamship Line, Inc. The Tewksbury was moored in a relatively protected area flush against the face of a dock on the outer bank just below a hairpin bend so that no opportunity was afforded for ice to build up between her port bow and the dock. Her shipkeeper had left around 5 P.M. and spent the evening watching television with a girl friend and her family. The collision caused the Tewksbury's mooring lines to part; she too drifted stern first down the river, followed by the Shiras. The collision caused damage to the Steamer Druckenmiller which was moored opposite the Tewksbury. Thus far there was no substantial conflict in the testimony; as to what followed there was. Judge Burke found, and we accept his findings as soundly based, that at about 10:43 P.M., Goetz, the superintendent of the Concrete Elevator, telephoned Kruptavich, another employee of Continental, that the Shiras was adrift; Kruptavich called the Coast Guard, which called the city fire station on the river, which in turn warned the crew on the Michigan Avenue Bridge, this last call being made about 10:48 P.M. Not quite twenty minutes later the watchman at the elevator where the Tewksbury had been moored phoned the bridge crew to raise the bridge. Although not more than two minutes and ten seconds were needed to elevate the bridge to full height after traffic was stopped, assuming that the motor started promptly, the bridge was just being raised when, at 11:17 P.M., the Tewksbury crashed into its center. The bridge crew consisted of an operator and two tenders; a change of shift was scheduled for 11 P.M. The inference is rather strong, despite contrary testimony, that the operator on the earlier shift had not yet returned from a tavern [Swannie House] when the telephone call from the fire station was received; that the operator on the second shift did not arrive until shortly before the call from the elevator where the Tewksbury had been moored; and that in consequence the bridge was not raised until too late. The first crash was followed by a second, when the south tower of the bridge fell. The Tewksbury grounded and stopped in the wreckage with her forward end resting against the stern of the Steamer Farr, which was moored on the south side of the river just above the bridge. The Shiras ended her journey with her stern against the Tewksbury and her bow against the north side of the river. So wedged, the two vessels substantially dammed the flow, causing water and ice to back up and flood installations on the banks with consequent damage as far as the Concrete Elevator, nearly three miles upstream. Two of the bridge crew suffered injuries. Later the north tower of the bridge collapsed, damaging adjacent property. |

1960

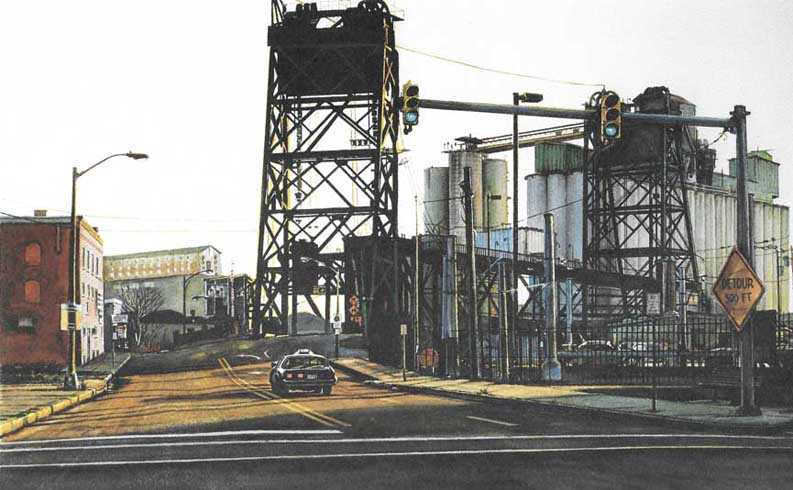

Michigan Avenue Bridge Lalli & Rote watercolor and history |

1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge 2004 Photos  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge over the Buffalo River Vertical lift bridge  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge ... Marine Midland Bank/HSBC Center  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge  1960 Michigan Avenue Bridge |