|

The Larkin Building,

Buffalo, NY: History of the Demolition

by Jerome Puma

1978

Note: Footnotes have not been included because plagiarism is a problem.

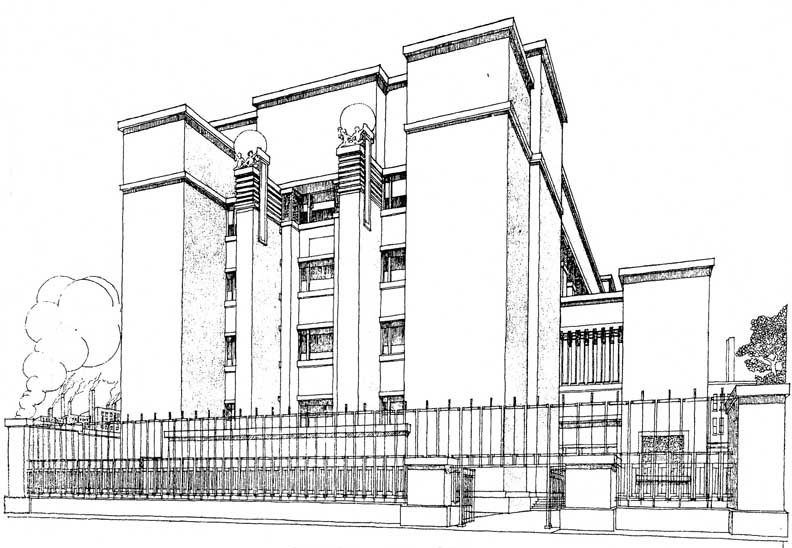

The Administration Building of the Larkin

Company of Buffalo, New York, designed in 1904 by Frank Lloyd

Wright and built in 1906 at 680 Seneca Street, became the focal

point of the vast Larkin industrial empire. Built during the golden age

of industry in Buffalo, the five story, dark red brick building drew

international attention for its many innovations. The circumstances

surrounding the destruction of this architectural marvel have never been adequately

documented and explained.

The Larkin Company was founded in Buffalo in 1875 by John D. Larkin as

a small soap manufacturing company. By the early years of the twentieth

century, the Company had reached the most prosperous era of Its

existence, and was manufacturing soap, household goods, furniture,

food, drugs, paint; in sho rt, almost everything. Serving as a

mail-order supplier to the entire United States, and operating numerous

retail stores in the Buffalo area, it is reported that money poured

into the Larkin Company offices at such a tremendous rate that it was

removed from the envelopes and deposited into baskets and barrels,

filling them rapidly.

Money was certainly not in short supply when the officers of the Larkin

Company commissioned Frank

Lloyd Wright to design their office building across the

street from the main factory. In fact, a $4,000,000 price tag did not

discourage approval of the project. At the time of demolition (1950) it

was estimated that replacement cost would be between seven and ten

million dollars.

The building was constructed of dark red brick, utilizing pink tinted

mortar. Five stories high, the main building was attached to an annex

of approximately three stories. The entire roof was paved with brick

and served as a recreation area for the building's employees, their

families and guests

The entrances of the building were flanked by two waterfall-like

fountains. Above the fountains were bas-reliefs by Richard W Bock, who

also designed the globes on the tops of the central exterior piers of

the building. These globes were removed by 1941 due to structural

problems associated with their weight, and where they are now, if

indeed they still exist, is not known .

Interior

The interior consisted of a

five-story central court or nave, surrounded by balconies. The upper

level contained a kitchen, bakery , dining rooms, classrooms, a branch

of the Buffalo Public Library, restrooms, a roof garden, and a

conservatory.

The interior walls of the building were made of semi-vitreous, hard,

cream-colored brick. Natural and artificial light was provided by

Wright-designed hermetically sealed double-paned windows, as well as

Wright-designed electrical fixtures, that enabled the employees to work

in comfort at their Wright-designed metal office furniture, while

breathing air from a Wright-designed "air conditioning" system.

Wright's use of magnesite in the building's interior is interesting,

since magnesite is mainly used to line the inside of steel-making

furnaces. It is also mixed with cement to make a compound used for

flooring.

In the Larkin Building, Wright

used magnesite that was mined in Greece and shipped to Buffalo.

Magnesite was used in the construction of stairs, doors, window sills,

coping, capitals, partitions, desk tops, and plumbing slabs. It was

reported that the floors of the Larkin Building were marble. In

reality, the floors consisted of a base of concrete, cushioned with a

mixture of wood fiber and magnesite, then covered with sheets of

magnesite.

Demise

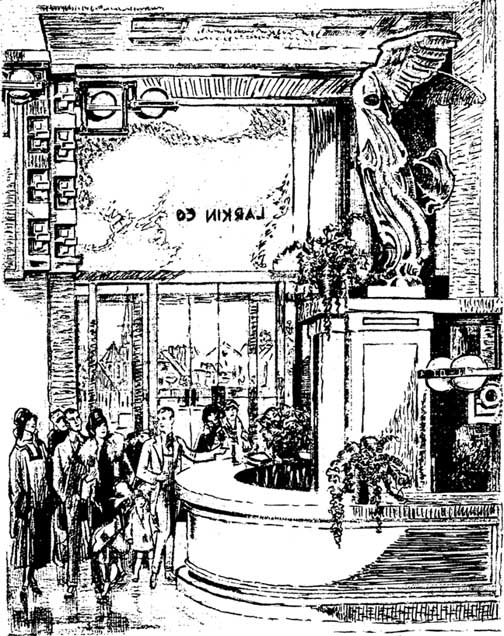

The beginning of the end of the

Larkin Administration Building can be traced to a press release dated

October 4, 1939. In this article, J. Crate Larkin, president and

treasurer of the Larkin Company, and Adam F. Eby, general retail

manager, announced that the Larkin Retail Store, located at 701 Seneca

Street, would move across the street to the Administration Building,

because it had 25% more floor space.

These executives stated that because of the rapid elevator in the

building and the large expanse of natural lighting, their new store

would be "one of the most attractive retail establishments in this part

of the country. However, to meet this end, extensive remodeling of the

interior began. The interior court was cleared of the familiar desks

that are so ubiquitous in Larkin photographs. The floors were carpeted

and the organ console and grand piano occupied the space. The court was

lighted by newly-installed diffused, glareless floodlights placed on

the fifth floor. Also, the main floor now contained sixteen indoor

"windows" where Larkin drapes and curtains were displayed against a

pastel background that was backlighted to simulate sunlight.

Full-length mirrors were installed and walls were repainted The area

surrounding the central court was partitioned to make three model rooms

for display.

The second floor was also partitioned into three model rooms. This

floor and the third floor held merchandise. The fourth and fifth floors

remained in use as office space for the mail-order branch of the company.

Ten of the double-paned windows that faced the parking lot were

transformed into display windows. On November 20, 1939 at 10:00 am, the

Larkin Retail Store was opened by Buffalo's mayor, Thomas L. Holling,

signaling the demise of the Larkin Administration Building.

The First Sale

From the time of remodeling in

1939 until 1943, business dwindled and the Larkin Company fell further

into financial troubles. The company began to sell various

buildings on the Larkin property. So, it came as no surprise

when on May 24, 1943, it was announced that the Larkin Building was

sold for an undisclosed sum to L. B. Smith, a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

contractor). Mr. Smith was the corporate head of a group of large

construction companies that dealt in coal strip-mining and

quarrying operations in Pennsylvania and West Virginia

At the time of sale, A. H. Miller, the comptroller of L. B.

Smith, Inc. said that the company had no definite plans for the

building. He did mention, though, that the Army had considered the possibility

of using the building to house offices of the War Department.

Tax Foreclosure

When business began to founder,

the Larkin Company changed its name to the Larkin Store Corporation.

When L. B. Smith bought the building, the Larkin Store corporation had

nine months remaining in its lease of the building. When the lease ran

out, L. B. Smith took no further action, abandoning the building until

it was taken over in a tax foreclosure of $104,616 by the City of

Buffalo on June 15, 1945.

The next time the Larkin Building appeared in the news was on November

I, 1946, The city had owned the building for over a year with only one

offer of $26,000 from an unknown prospect interested in its purchase.

Comptroller George W Wanamaker stated that the offer was too small and

reminded potential buyers that the building was assessed at $240,000

(Footnote 16). In an attempt to lure prospective buyers, the city spent

$6,000 in a national advertising campaign, With ads appearing in the

Courier-Express, Buffalo Evening News, Wall Street Journal, New York

Times, Chicago Journal of Commerce and other publications.

On November 20,1946, William E. Robertson, president of the United

Taxpayers League in Buffalo endorsed the ad campaign (Footnote 18). But

the Common Council tabled the ad plan for two weeks. During this time,

the council asked commissioner of Public Works Elvin G. Speyer to

report on the feasibility of transforming the Larkin Building into a

housing project. This idea was quickly termed improbable.

Finally in January , 1947, the ads began to appear. By March 29, 1947,

the city had received no offers for the structure. Officials blamed the

disinterest on the small amount of floor space in the building. The

assessment value had dropped to $224,000 and officials were showing

signs of panic. Comptroller Wanamaker sent a letter to State Selective

Service officials and asked them to consider storing state records in

the Larkin Building, but they refused.

On May 7, 1947, the Council accepted a $500 offer for a 90-day option

to purchase the building for $25,000. The offer was made by attorney

Maurice Yellen for an undisclosed client. At this date, the building's

assessment had fallen to $221,810.

Two months later, on July 7, Mayor Bernard J. Dowd suggested that the

the County take over the Larkin Building, widely referred to as a

"white elephant," for office space. Chairman Roy R. Brockett of the

Board of Supervisors named a committee of five to study the possibility

of conversion. It was thought that the county would occupy the building

before summer's end, but the idea never materialized.

By October 1947, the building was virtually useless Every double-paned

window was broken, the iron gate had fallen off its rusted hinges. and

the iron fence surrounding the building was sacrificed for a wartime

scrap collection.

By this time, the state had rejected an offer to use the Larkin

Building for emergency housing. Predictably, the county of Erie took no

action to convert the building for use as its Welfare Department.

Another $500 offer for a 90-day purchase option of $26,000 was proposed

by Sigmund J. Guefa, a local realtor, on behalf of another undisclosed

client on June 1, 1948. The Common Council refused to accept the option

because they felt it would force the city to sell the building for

$26,000, a small figure in their estimation.

To cite an example of the Common Council's ineptitude. just 20 days

later, on June 21,1948. the Council accepted another $500, 90-day

purchase option by Chester, Inc., another local realtor, on behalf of

yet another undisclosed client. Like all the others, this option fell

through.

Four months later, on October 1, 1948, another $500, 90-day option fell

through. This time, Magnus P. Benzing, general manager of the Magnus

Beck Brewing Company, 461 North Division St. had offered to buy the

Larkin Building for $26,000, that familiar figure Unfortunately, at the

end of 90 days. he had changed his mind.

By April 16, 1949, city officials were considering the building's

possible use as a recreation center. Ellicott District Councilman

Joseph F. Dudzick submitted a resolution to the Council which would

allow the Capital Expenditures Committee to take over the building for

conversion to basketball and tennis courts and gymnasium facilities;

Dudzick said:

There

is no wisdom in allowing the building to deteriorate further until it

becomes a pile of crumbling brick, especially when it can be put to

good use in building the bodies, minds and character of the city's

youth.

Despite this plea,

the resolution was defeated. Another suggestion by Ralph A. Coppola to

transform the building into a Buffalo Conservatory of Music was also

defeated.

The Second Sale

Four months later, on August 20,

1949, with an assessment value of $128,960, another offer to purchase

the Larkin Building was disclosed by the Hunt Business Agency for an

undisclosed client. The client planned to purchase the building for

$5,000, demolish it, and construct a "taxable improvement" costing "not

less than 100,000" within the next year and a half.

On September 13, 1949, the Council approved the $5000 offer without

even finding out with whom they were dealing. On October 8, 1949 it was

revealed hat the buyer was The Western Trading Corporation, 1100 Main

Street, Buffalo. The corporation estimated that it would cost $100,000

to demolish the building. It was noted that everything removable had

been stripped by vandals, including twenty tons of copper, light

fixtures, door knobs, plumbing, and even the boards used to keep the

vandals out. Also, it was estimated that it would cost $8000 to replace

the windows). Final sale was made on November 15,1949.

Even though the Larkin Building was vacant for seven years, public

outcry began only after demolition announcements were made. On November

16, 1949, architect J. Stanley Sharp stated in the New York

Herald-Tribune:

As

an architect, I share the concern of many others over the destruction

of Frank Lloyd Wright's world-famous office building in Buffalo. it is

not merely a a matter of sentiment; from a practical standpoint this

structure can function efficiently for centuries. modern engineering

has improved upon the lighting and ventilation systems Mr. Wright

used,

but that is hardly excuse enough to efface the work of the man who

successfully pioneered in the solving of such problems. The Larkin

Building set a precedent for many an office building we admire today

and should be regarded not as an outmoded utilitarian structure but as

a monument, if not to Mr. Wright's creative imagination, to the

inventiveness of American design.

Demolition

Demolition of the Larkin

Administration Building by the Morris and Reimann wrecking contractors

of Buffalo began in late February 1950 and was completed in July 1950.

The inordinately long period of time for demolition was due to the fact

that the building was "built to last forever." The floors of each story

were made of ten-inch thick reinforced concrete in slabs seventeen feet

wide and thirty-four feet long. The floors were supported by

twenty-four inch steel beams, which are now shoring up coal mines in

West Virginia, and the bricks and stone were used to fill the Ohio

Basin.

The Empty Site

One year after demolition, in May 1951, the Western Trading

Company announced pans to build a truck terminal on the site. The

building's plans, drawn by I. A. Germoney, called for an L-shaped

building with frontage of 280 feet on Seneca St. and extending 280 feet

to Swan St., where the frontage would be 50 feet. A 50 feet by 70 feet

section would contain two stories, the upper story containing offices.

The company filed with the National Production Authority for permission

to build the terminal at a cost of $150,000 to $200,000.

On November 24, 1951, the Western Trading Company petitioned the Common

Council to allow them to change the site of their proposed truck

terminal from the Larkin site to a lot at Elk and Dole Streets, because

"it was less crowded" They also stated that if they did build on the

Larkin site, a valuable parking lot for the customers and employees of

the Larkin Terminal Warehouse would be lost. Three days later, the

Common Council agreed to ease the pact; thus a parking lot now stands

on the site of Frank Lloyd Wright's greatest contribution to Buffalo,

the Larkin Administration Building.

Postscript

Today, the Larkin Company is gone,

as well as the Administration Building. Memories barely survive of the

once-grand building and the business empire. The last time anyone

publicly discussed the Administration Building was in the Courier-Express

on December 22, 1965.

The loss of the Larkin Building was a tragic one for Buffalo and the

entire world. In presenting the facts concerning its demise, it is

hoped that in the future we will study the value of a structure and

avoid the destruction of mile-stone

architecture.

© 1978 Jerome Puma |

![]()