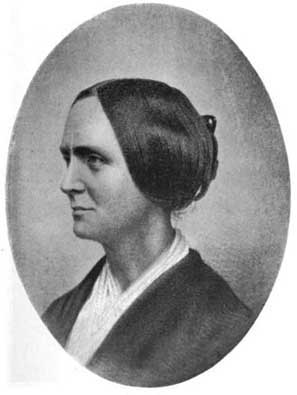

Abby Kelley

|

ABOLITIONISTS IN BUFFALO

Abby Kelley 1811 – 1887 By John Fagant

The Garrisonian abolitionists from New England began their New York State tour in Buffalo on August 6th of 1842. The celebrated former Quaker woman Abby Kelley spoke for 3 evenings (6th, 7th and 8th) to increasingly large and overflowing audiences. Kelley and Dr. Erasmus D. Hudson had come to Buffalo to arouse the western New Yorkers out of their apathy toward the anti-slavery movement and apparently succeeded in doing so. Hudson reported that “A glorious gathering took place in Buffalo. Such a revival of spirit was produced by the powerful application of truth to the consciences of the people during the convention, by Abby Kelley, as was never before known in Buffalo.” Or, in simpler terms, Abby Kelley had transformed the city’s attitude with her magnetic and spell-binding rhetoric. So who was this Abby Kelley and why should she be looked upon as an important abolitionist in the years before the Civil War?  Born in Massachusetts with a Quaker upbringing, Abby Kelley became an American abolitionist closely associated with William Lloyd Garrison and the American Anti-Slavery Society. She was well-known as an anti-slavery lecturer at a time when women speakers were mocked, heavily critiqued and sometimes even physically abused. She began her abolitionist crusade in 1838, lecturing by 1839. Dressed in her simple and plain Quaker dress, this young, attractive woman was uncompromising in her words and scathing in her logic and could quiet the arguments of any man in her day. Yet, due to the misogynistic culture of the times, the press and clergy were unrelenting in their insistence on silence and submission for women. She was denounced as a “Jezebel” and an “infidel”, forced to avoid the pelting of stones and rotten eggs, and somehow braved the wrath of the prejudiced public to bring the abolitionist message across the North. The author Dorothy Sterling said of her: “A radical member of the most radical wing of the anti-slavery movement, she believed that the nature of American society had to be changed in order to abolish slavery and root out people’s belief in white supremacy.”A dangerous adversary, she was sharp tongued and intense, tough and implacable. She was a fiery and dedicated advocate for the slave at a time when intense courage was needed to be so, especially for a woman. Yet privately she was a charming, loving, sentimental and loyal friend. RISE to FAME The 1840 annual American Anti-Slavery Society meeting in New York City proved to be a contentious one, with Abby Kelley right in the middle of it. The New England Garrisonians were battling for control of the society with those favoring a political response to ending slavery. When Kelley was nominated for a position on the business committee, all fire and brimstone broke loose. People rose to their feet in protest. A woman cannot serve on a committee. Women had never served and the word “persons” meant men. Despite the deafening disapproval, Kelley won on a vote by the convention. Almost half of the society walked out and later formed their own anti-slavery society, the American and Foreign Anti-slavery Society. Unfair or not, Kelley was widely blamed for causing this rift. “Abby was the leader in the affair – the bombshell that exploded the society”. Following the convention, a new phrase was coined, “Abby Kelleyism”, defined as “an unlovely and unteachable sport”. Throughout the rest of 1840 and 1841, Miss Kelley took to the lecture circuit in Connecticut and Rhode Island. The New York City convention turned out to be minor compared to what she experienced in these two states. Kelley developed a toughness that all abolitionists needed during these early years. Confrontational politics was a given as verbal abuse was common with physical abuse always a possibility. In New Hampshire, a rum bottle was thrown as her, followed by an armada of stones and clubs. A drunken bully came down the aisle with a rifle and charged that “the first person who speaks for the (N-word) shall have the full charge of this gun.” An accusation that truly hurt her was a preacher’s reference to her as a Jezebel. He informed his parishioners that a “Jezebel” had come to their village “with brazen face and fascinations exceeding those of her Scriptural prototype”. She was “a servant of Satan in the garb of an angel of light.” Her aim was to “entice and destroy this church.” This “vile character” “traveled by night and by day, always with men, and never with women”. Kelley was in the audience listening to this description of her. She sat there in stunned silence wondering how anyone could accuse her in such a way. ABBY KELLEY in BUFFALO 1842 In July of 1842, the American Anti-Slavery Society organized a massive three month lecture tour through western and central New York. Beginning in August in Buffalo, the westernmost city, it would end by late October in Cooperstown. The purpose of the tour was to revive the anti-slavery sentiments of the region which had essentially disappeared due to the economic Panic of 1837 and the antislavery schism of 1840. Eight lecturing agents were hired, including Abby Kelley, and they were to work in groups of two or three as they toured the various cities and villages. The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser and Journal of August 8th wrote of her visit to the city in a complimentary but ultimately condescending style. Abby Kelley.—This somewhat celebrated lady has favored our city with a visit, and addressed upon two occasions already, the people of Buffalo, in crowded audiences… she is young, comely and eloquent, with a voice of music and a mind of power.Despite the above compliments, the correspondent for the Advertiser overall was not convinced by Kelley’s arguments and finished the article in quite a boorish and condescending manner: Her words fail to carry conviction with them, and upon the whole it may be questioned if her labors advance the cause she seems so solicitous to serve. It is much to be regretted that a lady with such advantages of person and talent, should not have found a more appropriate sphere of action – one better befitting her sex.If the Advertiser’s reporter thought of Kelley and the anti-slavery cause as little more than a passing fad, the increasing crowds that came to her lectures make one hope that at least the Buffalo public began to have a more progressive view. At least one Buffalo anti-slavery man experienced a rebirth in enthusiasm for the cause and seemed to have developed quite a liking for the young lady. George W. Jonson, Buffalo’s antislavery and Liberty Party man, commented in his journal on Miss Kelley’s time in the city. Sat. 6. … Abby Kelly (sic), the famous anti-slavery lecturer arrived in the city and lectured. Heard her at evening … Abby has a fine form, about the medium height, features if not handsome, very interesting, a sweet voice, perfect enunciation, a winning manner – in a word, all the powers and graces of elegance. What logic! What pathos! What wit, humor, sarcasm, indignation, scorn! What self-possession!Jonson also mentioned how difficult it was for the speakers that followed Kelley. The crowd generally dispersed after she finished, leaving just a dozen or so present. After Buffalo, Kelley spoke at Lockport on August 9th, Leroy on August 16th, Albion on August 19th, and Perry on August 21st. On Friday August 26th, she joined several others – including Frederick Douglass – in Rochester. It would be another year before Douglass would make his first appearance in Buffalo. ABBY KELLEY and the 1843 LIBERTY PARTY CONVENTION August of 1843 was a high point in Buffalo’s role in the American Anti-slavery Movement. Frederick Douglass and Charles Lenox Remond gave a series of lectures early in the month that represented the Garrisonian faction of the movement. A National Convention of Colored Citizens met in mid-August and the newly formed political party, the Liberty Party, met in late August in a tent at the Park (now Lafayette Square). The Liberty Party had formed due to the belief that the Garrisonian tactic of “moral suasion”, non-violence and anti-political thought had failed. Although both groups worked for the same cause – the end of slavery – they more often than not battled each other. Abby Kelley was a Garrisonian who argued against the beliefs of the Liberty Party. The Party, in turn, wrote scathing reviews of Kelley and other Garrisonians. When the Liberty Party scheduled their convention, Kelley decided to travel to Buffalo and attempt to get on the speaker’s platform and defend her ideals. As it turned out, she was popular with the Liberty delegates, who greeted her with “three rounds of applause.” George W. Jonson noted her presence at the Convention in his journal. Thurs. 31. …Convention re-assembled under the tent in the Park at 9 A. M. A large audience filled the tent. Singing as yesterday by Geo. W. Clark. Discussions continued. By permission and on my motion Miss Abby Kelly (sic) addressed the convention. She spoke in opposition to the policies of the Liberty Party, and was patiently listened to.Kelley was allowed to discuss the principles of the American Anti-Slavery Society and in doing so she became the first woman in American history to officially address a national political convention. Indeed, it is fascinating to realize that not only did Kelley have the courage to stand up and address her convictions to a group that disagreed with her, but also that the Liberty Party allowed for such an open discussion. In the end, Kelley and many of the Liberty delegates admitted that they had more in common than previously thought. LEGACY Abby Kelley devoted most of her active years to the cause of anti-slavery and women’s rights. Her influence was felt by many who followed her, including future women’s rights’ advocates Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony. In 2011, she was inducted into both the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the National Abolition Hall of Fame. SOURCES Dorothy Sterling, Ahead of Her Time, Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery (W. W. Norton & Company, New York 1991) Nelson Terry Heintzman, “Not a Scintilla of Abolition in Buffalo”, the Rise of a Liberty Man – as Revealed in the Journals of George Washington Jonson Gregory P. Lampe, Frederick Douglass, Freedom’s Voice, 1818-1845 (Michigan State University Press, East Lansing) Buffalo Commercial Advertiser & Journal, August 8, 1842 David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass, Prophet of Freedom (Simon & Schuster, New York) 2018 Reinhard O. Johnson, The Liberty Party, 1840-1848 (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 2009) Henry Mayer, All on Fire, William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (St. Martin’s Press, New York 1998) |

Page by Chuck LaChiusa in 2021

.| ...Home Page ...| ..Buffalo Architecture Index...| ..Buffalo History Index...| .. E-Mail ...| ..