Minoru

Yamasaki

|

|

|

|

| Pacific Science Center Seattle, Washington 1962 |

IBM Building Seattle, WA 1964 |

M&T Bank Buffalo, NY 1964-66 |

Rainier Tower Seattle, WA 1977 |

M&T Bank, Buffalo, NY Seated: Minoru Yamasaki and M&T President Charles W. Millard, Jr ... Standing: M&T Executive Dudley M. Irwin and [Buffalo] Architect Duane Lyman Source: M&T files / Buffalo News, August 28, 1963 |

Minoru Yamasaki, (born

December 1, 1912, Seattle, Washington, U.S.—died February 6, 1986,

Detroit, Michigan), American architect whose buildings, notable for

their appeal to the senses, departed from the austerity often

associated with post-World War II modern architecture.- Encyclopaedia Britannica (online Dec. 2018) |

| Now that I’m about to turn

seventy I finally feel able to reveal a shameful secret: I was a

teenage Yamasaki addict. I have no good excuse for why I got hooked,

but Minoru Yamasaki was the first contemporary architect who entranced

me. I had already begun my architectural self-education with the early writings of Ada Louise Huxtable in The New York Times, where in 1962 she praised the plans for Yamasaki’s Robertson Hall of 1961–1965 (home of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs) for the way in which “Greco-Roman and Far Eastern influences blend in a series of slender classic columns of Oriental lightness, in a top floor suggesting the cornice of a temple, and in a reflecting pool” and for how “the undertones of the past emerge subtly in a quite advanced and experimental construction.” I thought it was wonderful, too. ... white quartzite colonnade of Yamasaki’s newly completed Princeton Parthenon. - Martin Filler, Review of Minoru Yamasaki: Humanist Architecture for a Modernist World (online March 2019) |

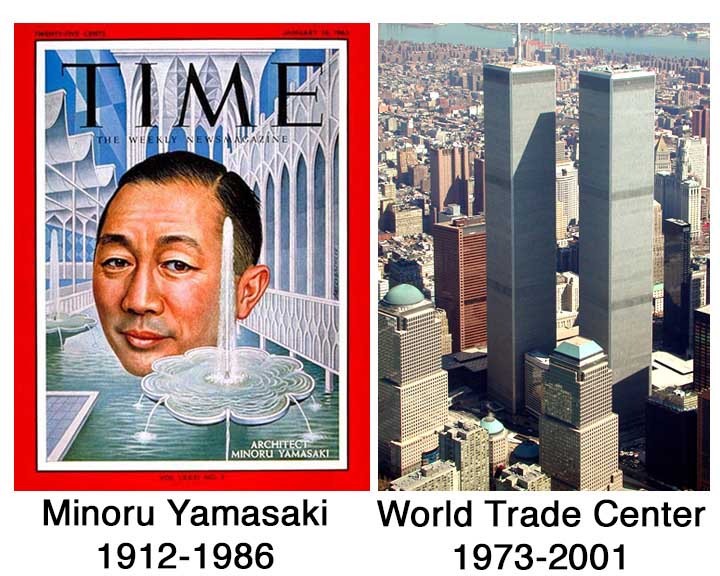

| Minoru Yamasaki, who

practiced in the Detroit area for over forty years, was one of the

world's best-known architects in the early 1960s, appearing on the

cover of Time magazine, serving on President Kennedy's

committee to redesign Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., and

being selected to construct the World Trade Center in New York, which

was briefly the tallest building in the world. His popularity arose from a unique form of architecture developed in the 1950s which melded his interest in invoking feelings of "serenity" and "delight" with insights gained from studying historical buildings in Europe, India, and Japan. His work offered a gentler, more decorated style of modernism distanced from the obsession with function or structure that characterized much of contemporary architecture. - Sarah Cox, "Yamasaki's Most Important Architecture In & Around Detroit," Curbed Detroit, 2013 (online Dec. 2018) |

| Yamasaki’s early training

and experience were influenced by the austerity and practicality of the

Modern and International Style movements. However, in

1955, his perspective on the state of architecture and his personal

aesthetic ambitions substantially changed. That year, he was

commissioned to design the U.S. Consulate in Kobe, Japan. While there,

he took the opportunity to embark on an architectural heritage tour of

Japan, Italy, and India. Having never traveled outside the U.S., the

trip proved to be eye-opening and career changing. As he described in his 1979 autobiography, the Japanese temples hidden amongst the crowded city streets made a particular impact. He was most taken, he said, by the element of surprise he experienced when emerging from the city’s commotion into the temple’s peaceful gardens and pools. In Italy, he studied Renaissance architecture in Venice and Rome, admiring their public squares and soaring Gothic cathedrals, whose texture and ornamentation are unmatched anywhere. Finally, he visited India and was awed by the sense of aspiration that the Taj Mahal’s silhouette against the skyline elicited in him. From these travels, Yamasaki developed an architectural philosophy that shaped the rest of his career. He openly eschewed the monotonous “glass boxes” that his contemporaries designed. Instead, Yamasaki sought to humanize architecture by combining historic decorative elements with new technology. In a 1962 speech in Seattle, he articulated his disillusionment with modern architecture, declaring it to be in a state of anarchy. Architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable perhaps best described it in a 1962 New York Times article: “The work is so characteristic of its designer that it could be picked out as Yamasaki’s in any simple guessing game,” she wrote. “There are pools and plants, skylights and courts, domes, vaults, arches, arcades, canopies and colonnades. Materials are sumptuous; surfaces are intricate. These are exotic, elaborate designs intended to delight the senses.” He did all of this using innovative structural engineering methods and modern materials, such as pre-cast concrete. Although frequently criticized for being over-decorated like “wedding cakes” or “jewelry boxes,” his designs were also often praised for being interesting, if not beautiful to experience. At the very least, his work never lacked controversy and was always distinctly Yamasaki. - Denise McGeen, "Minoru Yamasaki (Dec. 1, 1912 - Feb. 7, 1986 )," in HistoricDetroit.org (online Dec. 2018) |