The Millard and Abigail Fillmore House Museum - Official Website

![]()

The

Millard and Abigail Fillmore House Museum - Official Website

Partial

reprint

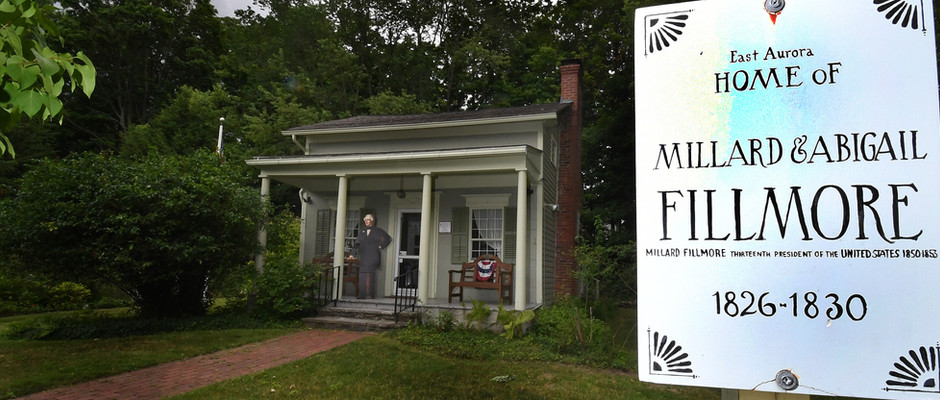

How to spend a summer day in Western New York: tour Millard Fillmore’s house By Jeff Schober Buffalo Tales  The home of Millard Fillmore and

his family, with a cardboard cutout of the 13th president on the porch.

© photo by Steven D. Desmond

The village of East Aurora holds a rare claim on presidential history: it was home to Millard Fillmore, the nation’s 13th president. For more than 40 years, Fillmore’s house at 24 Shearer Avenue, just off Main Street, has been open to tourists. Fillmore is not a well-known president, and is generally ranked in the bottom 10 by historians. But for fans of American history, presidential sites offer a unique experience and troves of information. “If you don’t know your history, you don’t know your future,” Kathy Frost, curator of the Millard Fillmore Presidential Site, said. “Millard Fillmore is our hometown son. He was born in New York State. To think that he built this house and found this area worthy of living in, and all the contributions he made to the city of Buffalo… If people knew his history, I think they’d honor him more.” Joan Bozer, one of founding members of the Buffalo Presidential Center and former Erie County Legislator, believes Fillmore made important contributions to Western New York. “Fillmore founded so many of our major institutions,” she said. “He helped establish the University at Buffalo and the Grosvenor Library. Everywhere you turn, he’s got his footprint. He presided over the first meeting to bring Fredrick Law Olmsted to Buffalo to talk about creating a park for us. Celebrating him raises Buffalo’s image.” Fillmore, who was born in Central New York but moved to East Aurora as a young man, was president from 1850-53. Elected as Zachary Taylor’s vice president, he assumed office after Taylor’s sudden death only 16 months into his tenure, during a time when sectional differences were brewing. Within a decade, the nation would be ripped apart by the Civil War. “We address that here during the tour,” Frost noted. “The Compromise of 1850 is part of his life and legacy. We discuss all the parts of that bill. I think those poor Senators and the president did the best they could to put a band-aid on the problems. We also tell stories that hit on the personal. People love to know what a real person Millard Fillmore was and what his struggles and triumphs were.” House relocated in 1930 Until recently, it was believed that Fillmore was the only president to build his own house. Several men designed their homes — most notably Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia. But Fillmore used his hands to cut, plane, and join the logs together, with the help of several friends. Docents at the Fillmore site, however, learned that Ulysses S. Grant hand-built a log cabin near St. Louis for his wife before he became president, although the couple did not live there very long. “When we found out this wasn’t the only original house built by a president, we were humbled,” Frost said.  Looking through the strings of Abbie Fillmore's harp. © photo by Steven D. Desmond Originally constructed in 1826, the Fillmore home was located on Main Street in East Aurora, not far from the Roycroft campus. It was nicknamed “the Honeymoon Cottage” when Fillmore married his wife, Abigail Powers. Their son, Millard Powers Fillmore, was born in the house. (The boy was called “Powers” for much of his life. It was not uncommon for men to be given their mother’s maiden name, which is where “Millard” originated.) Their second child — daughter Mary Abigail, nicknamed “Abbie” — was born in Buffalo. Fillmore later lived in two other Buffalo locations, but neither of those dwellings still stand. According to Frost, he had a home in the city on Franklin Street near Huron, not far from the current Convention Center. In 1858, he moved into the Hollister mansion, which was demolished in 1920 to make way for the Statler Hotel. The East Aurora home is the only Fillmore commemorative site in the nation. He is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Years after he died, Fillmore’s home fell into disrepair before it was relocated to Shearer Avenue in 1930. “The house was saved by a fabulous woman named Margaret Evans Price,” Frost explained. “In 1930, there was a small start-up company in East Aurora called Fisher Price Toys. Mr. Irving Price was her husband. She knew the historical value of the house and saw the charm in it. It had been vacant and was in need of repair. She turned to her husband and said, ‘I’d love to have that house as my art studio.’ Like every good husband, he said, ‘Yes, dear.’” Margaret Price was an artist and illustrator of children’s books. Although the Prices lived in a different home in East Aurora, she maintained the house as a studio for the next 43 years. After she passed away in 1973, the Aurora Historical Society purchased the property, raised $30,000 for renovations, and opened it to history buffs in 1979. The home is filled with actual items from the Fillmore family — tea cups, bedsheets, chairs, and even Abbie’s harp. There are also several period pieces to match the era. One of Frost’s favorite spots is the exposed beam that served as the back door of the original house. It is hand-hewn lumber, and she often runs her palm over it, reflecting that a future president shaped this very piece of wood.  Curator Kathy Frost touches the hand-hewn beam shaped by Fillmore at the back of the house. © photo by Steven D. Desmond Struggles and triumphs

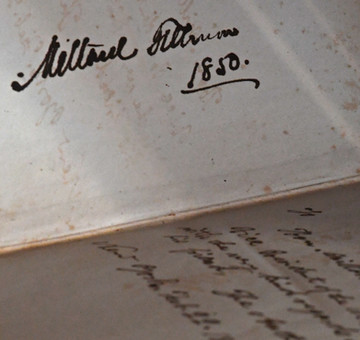

After working as a docent for nearly 30 years, Frost is an expert on Fillmore’s life and times. “First, he was poor,” she said. “Of all the presidents, we feel Millard Fillmore had a most humble beginning of life. He is born in a log cabin and doesn’t have much education. He is self-taught. Reading is his love, and he is a lifelong learner. He studies under a judge and is a lawyer by 23. He has a new lease on life when he comes to East Aurora. He was verbose and popular and began a political career.”   Fillmore's signature,

dated 1850. © photo by Steven D. Desmond

Fillmore

served in the New York State Assembly in Albany and was elected to the

House of Representatives before being selected to run as Vice

President. After leaving the Oval Office, tragedy struck.

“He’ll lose his wife and daughter within a short time,” Frost explained. “Abigail, his wife, dies in Washington D.C. three weeks after Fillmore was no longer president. They had attended the inauguration of Franklin Pierce. She had a cold that quickly turned into pneumonia.” The inauguration of Pierce, in March 1853, was a gloomy affair for many involved. The president-elect’s 11-year-old son, Benny, had been killed when a train derailed three months before. His parents had ridden the train with him, but they walked away from the accident unscathed. That, in addition to sectional divisions among states, left the new administration with an aura of defeat. Fillmore’s heartaches were soon to follow. “After Abigail died, the following year, his daughter Abbie will come back to East Aurora, and cholera kills her,” Frost said. “It happened overnight. She was 22. She visited her grandparents here in town and became ill. Losing a wife and a daughter in just over a year’s time is a lot to handle. But he persevered.” Historian Paul Finkelman, author of Millard Fillmore, a 2011 biography that was part of a presidential series published by Times Books, is not a fan of East Aurora’s star citizen, as evidenced from his quotes in the attached CBS video. Finkelman spoke about his book at the Buffalo History Museum a decade ago, when it was newly published. He believes that Millard Fillmore was on the wrong side of history. From the opening pages of his book:

Finkelman does mention Fillmore’s support for Union causes during the Civil War, raising money for war relief and assembling a symbolic troop of aging men. He also acknowledges the former president’s involvement in civic enterprises around Buffalo.  A close up of the quilt pattern in the upstairs bedroom. © photo by Steven D. Desmond Local historians are willing to elaborate those contributions in a way that Finkelman does not. In 1868, for example, Fillmore chaired a local committee that invited parks designer Frederick Law Olmsted to the city. The ensuing park system that Olmsted created remains a point of pride for Buffalo.  © photo by Steven D. Desmond “Millard

Fillmore played a role,” said Francis R. Kowsky, emeritus professor for

Buffalo State College, where he taught for 36 years. Kowsky is the

author of The Best Planned City in the World, a 2013 book that

chronicles the Buffalo parks system. “It was an honorary role more than

anything else, but it was important. Fillmore died in 1874, so he

didn’t live to see the whole thing played out on the ground. After he

left the presidency, he was called ‘the Sage of Buffalo.’”

Frost insists that the University at Buffalo would not exist without Fillmore. She explained that several local doctors — friends of Fillmore — tried to open a medical school but struggled to receive accreditation from New York State. “Millard Fillmore’s law firm got them accreditation to become a teaching school,” Frost said. “That small start of a medical school morphed into UB, which now offers many degrees.” Finkelman’s book concludes with these lines: “In retirement, Fillmore opposed emancipation and campaigned for a peace that would have left millions of African Americans in chains. In the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues of the age: immigration, religious toleration, equality, and most of all, slavery.” While Frost acknowledges Fillmore’s failures, she disagrees with Finkelman’s negative interpretation. She has participated in different forums with Finkelman, and respects his expertise, but she prefers to focus on Fillmore’s accomplishments, especially post-presidency. “In 1858, he marries for a second time,” she said. “Caroline Carmichael MacIntosh is a widow from Albany. His friends introduce them. She is thrilled to be meeting a former president. She is savvy about her money, and when they decided to marry, there was a prenuptial agreement. Whatever she owned was hers. He had nothing. There was no retirement money for a former president. She agrees to pay him $10,000 a year to be her financial advisor, and he signed on the dotted line.” Stories like these are part of the tour at the house in East Aurora.  The Fillmore family graves at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo. © photo by Steven D. Desmond |

| Also on Buffalo

Architecture and History: The Millard and Abigail Fillmore House Museum, East Aurora |