John Milburn

On this page:

Source: The True Story of the Assassination of President McKinley at Buffalo  Mr. and Mrs. McKinley at Canton, Ohio Source: President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition  Source: President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition  Source: The True Story of the Assassination of President McKinley at Buffalo   Postcard Canisius High School parking lot where Milburn House was located before the school razed it in the late 1950's. Photo by C. LaChiusa |

The text below is an excerpt from the chapter entitled "Pan American Exposition: World's Fair as Historical Metaphor" as found in "High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York," by Mark Goldman . Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983.

(Mark Goldman - LINKS)September 4 - The President Arrives

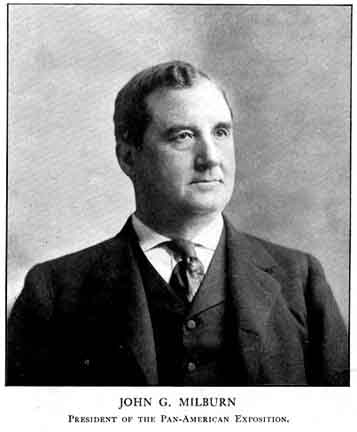

Several minutes later the train pulled into a special platform built at one of the entrances to the exposition grounds. Wearing a black frock coat and a high, black silk hat, President McKinley, his right arm tightly around his wife's waist, disembarked. Following a short and ceremonious greeting by John Milburn, the head of the exposition's board of directors, President and Mrs. McKinley, watched by a crowd of more than sixty thousand, stepped into a low-wheeled victoria drawn by four exquisite trotters, and made a quick tour of the exposition grounds. The McKinleys were then driven to John Milburn's home on Delaware Avenue, about one mile south of the exposition. They were scheduled to return to the exposition the next day.

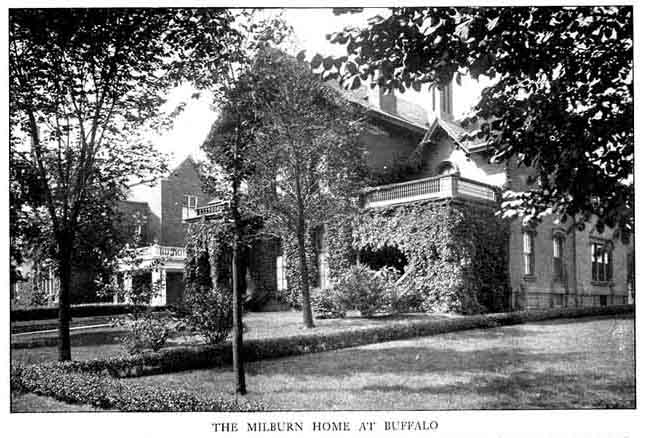

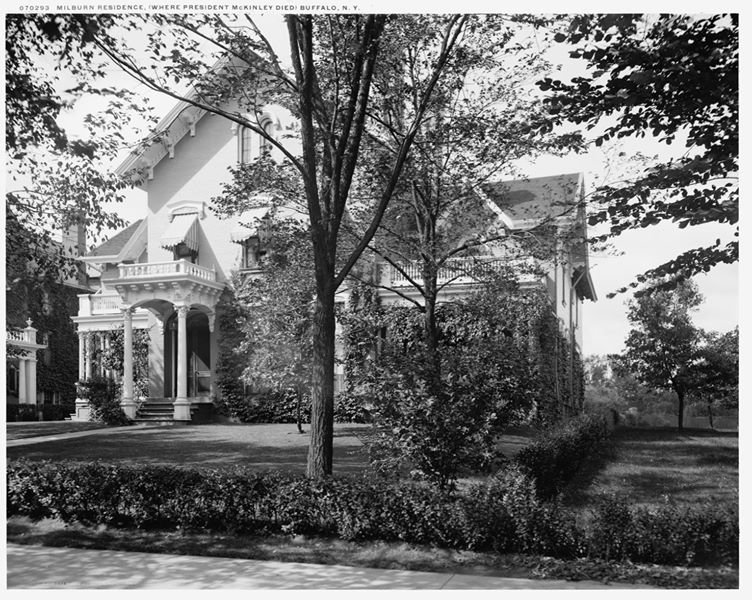

The Milburns were accustomed to entertaining important visitors. Earlier that summer the Roosevelts had stayed with them, as had the French ambassador and his family. But clearly the president was different, and in anticipation of the visit Milburn had completely renovated his large wooden home. The Milburns were concerned about their guests -- not the president, an affable, easy going man who liked nothing more than smoking a cigar (he smoked over twenty per day) in the company of robust men -- but rather Mrs. McKinley. For in spite of the president's best efforts to hide it from the public (and even his best friends), the Milburns knew, as did the rest of the country, about the first lady's epilepsy. While no mention was ever made in the press about Mrs. McKinley's illness, there were constant references to her fortitude, her ability to withstand the rigors of being the nation's first lady, and endless paeans to the president, whose solicitude of his sickly wife embodied, it was said, the most admirable of husbandly virtues.

Because of Ida McKinley's illness the Milburns were not permitted to entertain as lavishly as they would have liked (when ambassador Cambon had stayed with them in July, the Milburns hosted an all night costume ball that people were still talking about in September).

There was a story circulating about Mrs. McKinley that at one 1uncheon given in honor of the president and his wife, the centerpiece was a large, stuffed American eagle. When the guests sat down, the thing began to bob its head and move up and down in jerky, lifelike movements. The effect on Mrs. McKinley was shocking. She had a fit on the spot. Thus, because of her unpredictable behavior and her discomfort around people (to avoid shaking hands, she always held a bouquet in her lap when in public), the Milburns planned no public receptions for their honored guests. There wasn't much time anyway, because the president wanted to see as much of the exposition as possible.

After the president had been shot

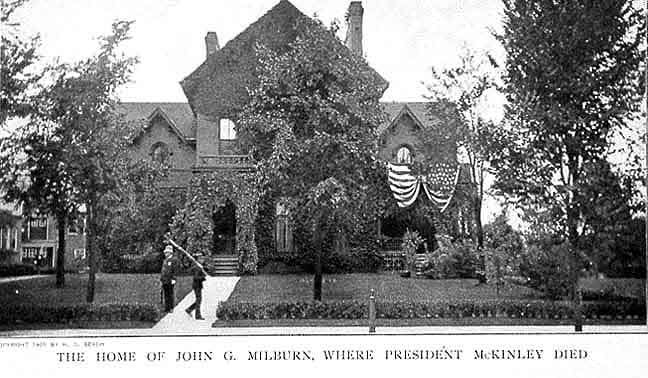

The Milburn house, so recently renovated, was now converted into a virtual military camp. On the outside it was surrounded by armed guards. Inside special telegraph machines had been installed as the house became the center of an international communications network. Across the street press tents were set up for the more than 250 newsmen covering the story, the most that had ever covered a public event. All of them rejoiced when Dr. Mann issued the first of many medical bulletins. The doctors were "gratified," Mann reported, by the president's condition. "The results," he said, cannot yet be foretold [but] hopes for recovery are justified."

As the president and the people of Buffalo settled in for what appeared to be a long period of recuperation (John Milburn engaged rooms for his family at a downtown hotel), the rest of the world reacted to the news.

After the president's death

Milburn announced that the exposition had lost over $6 million and that the Company would have to default on over $3.5 million in bonds. Milburn told the board of directors that he was going to Washington, where he would meet with New York's congressional delegation in an effort to convince Congress to pass a Pan American relief bill. He hoped, also to meet with President Roosevelt, who was reportedly sympathetic.

Yet Milburn's spirit was unbroken. He denied that the money lost on the exposition was "a foolish expenditure," as some had charged. The Pan American was, he said, a "masterpiece," and the city its "chosen showcase." Milburn asked the board to think of the millions of dollars that had poured into the city and to believe that the exposition had made Buffalo known all over the world, a city destined to rank with New York and Chicago.

Yet somehow Milburn wasn't convincing. His words didn't ring true. Nothing had turned out as Milburn had hoped it would. The exposition for which he had worked so devotedly had ended in a nightmare of violence and destruction. Once again Milburn looked ahead and, not liking what he saw, left. He was going to New York [in 1904], where he had accepted a partnership in a law firm. [Milburn later served as president of the N.Y.S. Bar Association.]

|

Erie

County, New York State McKINLEY DEATH CHAMBER WILL

SOON DISAPPEAR. Buffalo

will lose a cherished landmark within a few days when the Milburn house

will be a sad fond memory of citizens who eighteen years ago the world

joined in turning eyes and thoughts toward the spot where President

William McKINLEY lay dying. |

|

Memories of the demolition of the Milburn House I remember sitting

in class at Canisius High School, in that relatively new wing that runs

parallel to Delaware, and watching the clamshell tear into the Milburn

house, exposing an inner back stairway to sudden sunlight. The

strangeness of that sight sticks with me. |

web site consulting by

ingenious, inc.