The

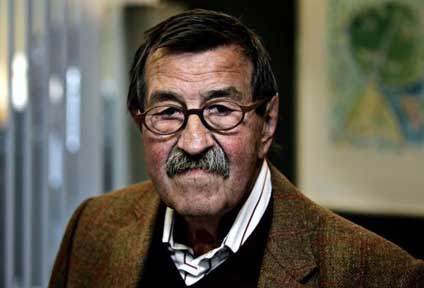

Nobel Prize-winning German novelist Günter Grass died this week. Grass

also wrote essays, poetry, and plays, including a one-act play, “Only

Ten Minutes to Buffalo,” that is kind of a lousy way to get to know his

work. But it’s amusing, in an absurdist sort of way. Buffalo is some

far-off place, somewhere in the vast oceanic landscape of North

America. Grass’s characters weren’t exactly sure where.

Graduate students, no doubt, will one day write dissertations

about Günter Grass’s minor works- but for almost half a century, so

many Americans and Europeans read his major works that the Nobel Prize

committee found it safe to award him the biggest gold medal of all in

1999. His acceptance speech was all about the political atrocities in

the late Generalissimo Augusto Pinochet’s murderous, fascist regime in

Chile. Rotten guys, those Chileans. Trained up by our rotten CIA. Grass

as awardee and as political activist was relentless in hammering all

the bad guys we supported. Then, suddenly in the summer of 2006, he had

a story of his own to tell.

For most of his adulthood, from 1959 to 2006, Grass was the famous

German novelist and Social Democrat, the moustachioed, tobacco-voiced

moralist whose total absorption with the lost city of his youth was

charming, inventively and insistently and also voluminously explicated

in his long shelf of books. His characters were political through and

through: little loud Oskar Matzerath, beating and screeching in The Tin

Drum, an allegory for his nation contained in the kid who willfully

refuses to grow up. The noble, doomed youth in Cat and Mouse, swimming

beautifully in Danzig harbor before the war made it Gdansk harbor and

sent all the Germans and their 800 years of being Danzigers away and

erased handsome youth. Less celebrated but beautifully drawn allegories

were Grass’s animal characters: The Flounder from the old folktale of

the fisherman and his wife; the post-apocalyptic The Rat with wise,

enduring rodents the witnesses to war; and the animal pathway to a

torpedoed ship full of German civilians in Crabwalk. In The Call of the

Toad, an old Polish woman and an old German man trying to negotiate

repatriating dead Germans to Gdansk, to turn it into Danzig again, if

only for the dead.

So much about Germnanness streamed from Grass - a book imagining a

meeting of all the major and many you-never-heard-of-them minor German

writers, a book like a hundred-year Lakota winter count but in German,

My Century. Of special poignant relevance to Rust Belters like us, who

mourn what was even as we invent and redefine, was Grass’s nostalgia

for the lost city.

This stream of writing about Germanness would have faded gently into

the musty halls of academe at Grass’s death, for Germans to us these

days are some amalgam of Mike Meyers’s SNL character Dieter, plus ads

for handsome and expensive automobiles, and nowadays some rumors about

the rebirth of Weimar Republic sexual adventurism in Berlin, and some

images of dour Angela Merkel scolding Vladimir Putin. Germans in the

20th century were not marginal or comical - they were, in the days when

Grass was coming up, simply enormous, huge. Huge intellectually,

technologically, politically. It took 15 years after World War II, by

about the time Grass became famous, for Americans to begin to accept

the message that Germany was no longer the threat that it had been.

Every Baby Boomer boy in America grew up fighting Nazis, not Japanese,

because the Nazis were the worst—until, suddenly, they weren’t anymore,

because the Communists had put up the Berlin Wall, and President

Kennedy not only stood with the former enemy but said aloud, that he,

too, was a Berliner. And if our President was a German, well, then,

somebody had to explain what had come before.

That was what Grass did. Grass had a use here. He was the German whose

books were correct: He was the critic of Nazis, but also the

unapologetic exponent of the genuineness and integrity of a great

cultural tradition. Useful, too - he warned the world against letting

the East Germans join what was, until November 10, 1989, just West

Germany. I’m German, I know who we are, I know what evil we’re capable

of. We are, he said, the people who gave you Auschwitz. Yes, there was

Peter Handke, but he was too opaque. Heinrich Böll, sure, but he was

too metaphorical in a literary way. Durrenmatt wrote plays. Grass,

however, wrote interesting, colorful, sexy, provocative novels, novels

you could get stuck in, like layer cakes, for Grass’s magical realism

was validated by Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s in his One Hundred Years of

Solitude.

So from 1959 to 2006, Günter Grass was the kind of German we needed:

intellectual, gruff, magically productive, relentlessly genuine about

his feelings about his lost city of Danzig but reassuringly resolute

that it was indeed lost. Then, suddenly, in one of our Iraq war

summers, the German storyteller and moral witness against the worst

that the Germans have been and could be hurriedly stepped forward, just

before the newspapers published their own stories, and admitted the

unthinkable - that he himself had been a member of the Waffen SS.

Feet of clay: Robert Byrd, the US Senator from West Virginia, got a

pass because he’d long since admitted having been a Klansman in the

1930s, before having become a New Deal, Fair Deal, New Frontier, and

especially a Great Society icon. And he’d been in some holler in West

Virginia, not in the heated nights of night-riding Alabama, Georgia, or

bloody lynch-mad Mississippi.

But Günter Grass’s admission was something else. This wasn’t just

admitting that he, like every other kid in Germany, had been a member

of the Hitler Youth. This wasn’t just admitting that he’d been a

soldier on the losing side. The Waffen SS were killers. No, murderers.

No, terrorists. They were sadistic Nazi criminals. Imagine a Freedom

Rider stepping out of the documentaries about Selma and admitting that

he and his friends had been in the same gang that had murdered those

four little girls in that church bombing reenacted with such horrifying

versimilitude in Oprah’s movie.

Then, worse, even while continuing to churn out work of actual literary

merit, having created so much of such enduring value, he clumsily or

willfully but undeniably did what too many on the left do when

objecting to the tactics of the late Israeli Prime Minister Ariel

Sharon or the newly re-elected Bibi Netanyahu—he lashed out at Israel,

the nation, rather than at the Likud’s policy.

That’s when he lost his credibility. Yes, back when he was 17, he was a

conscript, doing national service in 1944. He found himself reassigned

to the Waffen SS because most of the U-Boats had been sunk, so 10

months before the end of Hitler’s regime, Grass couldn’t achieve his

true boyhood aspiration of becoming a submariner. And no, he did not,

at age 17, commit any atrocities, because both he and the journalists

who exposed him agree that he manned an anti-aircraft gun until his

unit was overrun by World War II’s victors.

Clever like his rat, wise like his flounder, the young writer in the

1950s figured out that starting his career wouldn’t quite work had his

book-jacket blurb truthfully exclaimed that between the covers we’d

find how “former Waffen-SS volunteer Günter Grass explains the inherent

violence, murderous intolerance, and misogyny of his people in this

brilliant premiere novel set in the city now known as Gdansk, but which

he adamantly insists on calling Danzig.”

Nope. Clever a long time, he covered it up. Then, after an entire

adulthood being a critic and moralist, he forgot that he wasn’t allowed

into that performance space any more. Now we won’t read him, as we once

did. Now, the 20th century has been supplanted. Years from now, some

Russian will write about the viciousness of Putin’s Chekists, and then

will be revealed to have been one. Some Serb will speak movingly of the

old days in Mostar, the Tito days, before Milosevic got him all riled

up to kill Bosniaks. Some Somali, some Congolese, some deeply

insightful, nostalgic, magically inventive ex-cop from Iguale in

Guerrero: great career, strong anti-narco message, moral light - then,

oops, he forgot to mention that part. The complicity, being that the

best insight about villainy proceeds from the beast’s own interior.

Bruce Fisher is visiting profesor of economics at SUNY Buffalo State and director of the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.