Calling card

Excerpts from

Excerpts from

Victorian America: Transformations in

Everyday life, 1876-1915, by Thomas J. Schlereth. HarperCollins Publishers,

1991, pp. 117-118

Upon entering

a typical Eclectic Manse, a visitor encountered a front hall, usually six to eight

feet wide and twelve to twenty feet long, or considerably longer if it ran the length

of the house. Its decor indicated the character of both the dwelling and its inhabitants.

Decorating books recommended bright colors, a dado and a rail, and hand stenciling

or wallpaper. Most front halls before 1900 included a staircase to the second story.

A fully furnishedfront hall contained a hall stand, hall chairs, and a card

receiver. A family's articles of personal costume (hats,c oats, parasols, or umbrellas)

bedecked their hall stand. Here clutter was class. Hall stands often had seats, where

messengers, solicitors, and unexpected visitors rested while awaiting instructions.

If the hall stand had no seat, other furniture, such as leather upholstered settees

or a single straight side chair, might be provided.

Service people might temporarily occupy a hall chair, but they would never use the

card receiver, the third artifact necessary for any properly furnished hall. Like

the hall stand, the card receiver is now obsolete; so is the elaborate ritual of

calling and card leaving. During its American vogue, 1870 to 1910, card leaving became

an avenue for entering society, of designating changes in status or address, of issuing

invitations and responding to them, of presenting sentiments of happiness or condolence,

and, in general, of carrying on all the communication associated with middle-class

social life.

Done almost exclusively by women in the afternoon, calling and card leaving entailed

complicated social arithmetic. Since husbands did not normally accompany their wives,

the wife left her husband's card where she visited. If the lady of the house was

"at home," the visitor left two of her husband's cards on the card receiver,

one for the lady of the house and one for the lady's husband. She did not leave her

card, since she had seen the lady.

If, however, the visitor called but the lady of the house was "not at home," she left three cards on the receiver, one of her own (etiquette books prescribed that a lady should leave only one card for a lady) and two of her husband's. The contents of a family's card receiver were sorted and evaluated. Decisions then had to be made as to how to respond - to pay an actual visit or only a surrogate one by way of a card (a call for a call or only a card for a card). Mark Twain, writing in The Gilded Age, lampooned the intricacyof these social rituals by commenting: "The annual visits are made and returned with peaceful regularity and bland satisfaction, although it is not necessary that the two ladies shall actually see each other oftener than once every few years. Their cards preserve the intimacy and keep the acquaintanceship intact."

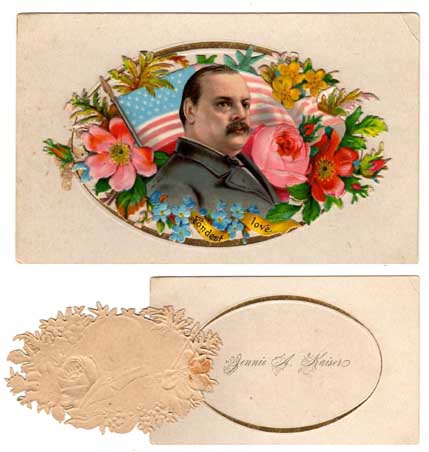

The upper illustration shows a calling card in the possession of the webmaster. The Grover Cleveland oval is raised up to the left - the lower illustration - revealing the caller's name.