Black Rock - Table of Contents

Historic Old Black Rock

By Austin

M. Fox

Reprinted with permission from the Austin Fox

estate and Buffalo Spree, Fall 1994

Black Rock - Table of Contents

Historic Old Black Rock

By Austin

M. Fox

Reprinted with permission from the Austin Fox

estate and Buffalo Spree, Fall 1994

At the outset, a reader might be inclined to ask,

"Where exactly is Black Rock?"

Even lifelong residents of Black Rock or fourth or fifth generation Buffalonians

might have problems with drawing boundaries for Black Rock.

Today Black Rock and Riverside are linked as one general residential, commercial,

and industrial entity bounded by the Scajaquada Parkway on the south, Elmwood Avenue

on the east, Kenmore Avenue on the north and northeast, Vulcan Street on the northwest,

and the Niagara River on the west.

The original Black Rock location

Historic Black Rock, however, extended from School Street, which runs into Niagara

near the Peace Bridge, to about as far as Austin Street, which is beyond the International

Bridge to Canada. Old Black Rock's western border was the Niagara River and its eastern

line was approximately the eastern boundary of the Mile Strip. New York State had

bought this mile-wide swath from the Seneca Indians in 1802 and shortly afterward

sold lots on this land. North of where the Scajaquada Creek empties into the Niagara

River near Tonawanda Street and Forest was called Lower Black Rock, and the area

south of that creek mouth was termed Upper Black Rock.

The black rock itself from which the locality took its name lay in the river just

north of the Peace Bridge. It was a large triangular shelf of darkish limestone that

jutted about 200 feet from the shore and rose four or five feet above the water.

It was river-current-sheltered and an ideal docking place for boats and for the oar-propelled

ferry across to Canada.

But the black rock was dynamited away in the early 1820s to make way for the Erie

Canal bed that paralleled the shore and proceeded via the Buffalo River to Buffalo

Harbor.

The commercial and social center of Black Rock at that time was the Niagara Street,

Breckenridge and West Ferry vicinity - about where the Rich Products complex

lies today. After the removal of "the rock," the ferry operated

from Squaw Island at the foot of West Ferry Street.

The War of 1812

Old Black Rock was the battleground for three American

resistances to British attacks during the War of 1812 and the scene of a daring naval

action that lifted American morale.

Lt. Jesse Elliott and a detachment of seamen stationed at the ship yard and blockhouse

near the mouth of the Scajaquada Creek captured from the British two armed vessels,

the Adams and the Caledonia, which had been moored off Fort Erie. At the same time

they released about forty American prisoners from the holds of those ships. The same

shipyard at Scajaquada Creek also built or refitted five naval vessels that helped

Oliver Hazard Perry win his stirring victory at Put-In Bay near Sandusky, Ohio in September,

1813, giving the U.S. Navy control of Lake Erie.

One British attack near the foot of West Ferry and Breckenridge in July of 1813 was

repulsed by a motley collection of militia, regular army soldiers, and a handful

of Seneca Indians, all under command of General Peter B. Porter.

Late in December of the same year, however, the Americans failed to stop the British

advance on the city of Buffalo. The British were bent on avenging the burning of

Newark (now Niagara- on- the- Lake), but the Americans could not hold them back at

the battle near the bridge over the Scajaquada, and the British moved up Niagara

Street with little further resistance and proceeded to burn Buffalo.

The third British move on Black Rock took place in August of 1814 when Lt. General

Sir Gordon Drummond was unsuccessfully trying to retake Fort Erie from the Americans.

To divert the Americans and cut off their supply lines from Black Rock, he sent a

force against the blockhouse and shipyard facility, but it was roundedly defeated,

and Drummond, having suffered terrible losses during his siege of Fort Erie, withdrew

toward Fort George at Newark. This marked the end of hostilities on the Niagara Frontier

during the War of 1812.

General Peter Porter

Black Rock's General Peter Porter had commanded the

American militia well at the battles of Chippewa, Lundy's Lane, and Fort Erie during

the 1814 campaign, and had planned the strategy that repulsed Drummond at Fort Erie.

He had also been wounded twice.

Unquestionably a brilliant leader and genuine hero of the War, Porter became the

leading citizen of the whole Black Rock area. He had been elected a congressman at

his former home in Canandaigua, where he had practiced law. But when he came to the

Niagara Frontier, a bachelor of thirty-seven, he devoted himself to his supply and

forwarding business as a partner in Porter and Barton. President Madison offered

him the command of the whole U.S. Army, but he declined. He was elected to congress

twice, and President John Quincy Adams made him Secretary of War, the first cabinet

post held by a Western New Yorker. He was briefly Secretary of State in 1815, and,

in 1816, he was one of the commissioners to determine the boundary between the U.S.

and Canada. When Black Rock lost out on its bid to become the western terminus of

the Erie Canal, he eventually moved his residence and business to Niagara Falls,

where he died in 1844 at the age of 74.

Buffalo annexes Black Rock

Because of the superiority of Buffalo harbor to the one at Black Rock, the commercial centrality of the region shifted to the Port of Buffalo. Black Rock lost more of its identity when it was annexed to the city of Buffalo in 1854. But industry along Niagara Street continued for some time. The Thomas Flyer Company, for example, made early automobiles and then Curtiss Jenneys during World War I and Curtiss dive bombers during World War II.

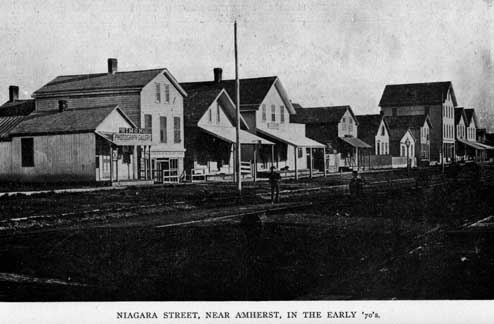

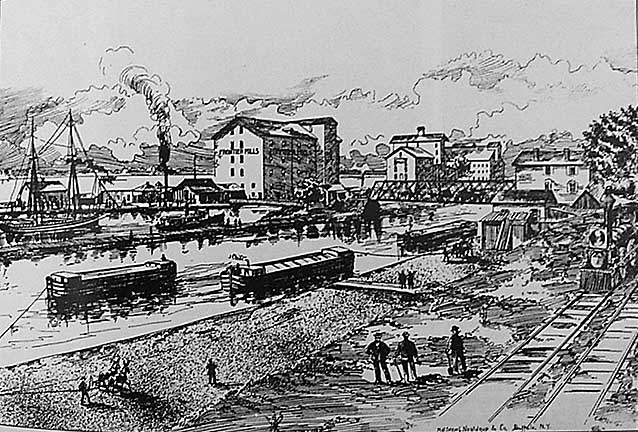

Niagara Street near Amherst, the 1870s.

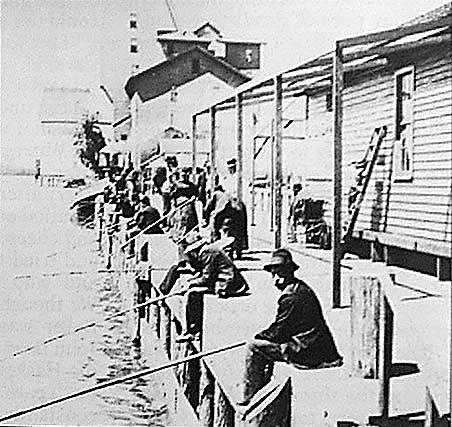

Fishing off the Bird Island pier, circa 1896

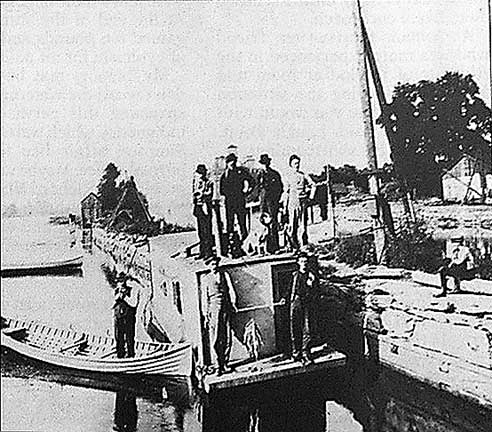

Guard Locks, Austin to Amherst Streets, about 1910.

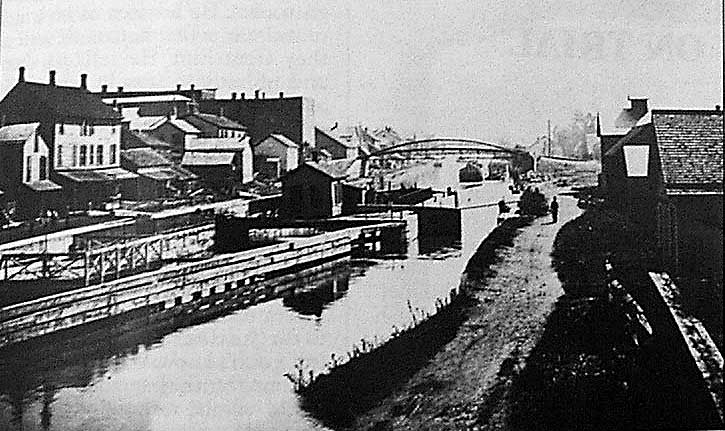

An old print showing mills at Black Rock

and a towpath with mules drawing barges, circa 1888.

Additionally, the Bird Island pier remained for some time a place for boarding the

pleasure steamers en route to the resorts on Grand Island. Squatters settled along

the canal towpath, but the state dispossessed them when it built the New York State

Thruway extension. Today riverboating, fishing, and the picturesque recreational

activities of the West Side Rowing Club still continue, reassuringly.

Few Buffalonians are aware of the treasury of history connected with Black Rock. The Riches have done much to stabilize the area, which is holding its own, but one hopes that its convenient location and historical tradition will attract good small businesses and stable families to energize its potential.

web site consulting by ingenious, inc.