Benjamin R. Maryniak - Table of Contents .............Soldiers & Sailors Monument - Table of Contents

|

The Soldiers & Sailors Monument

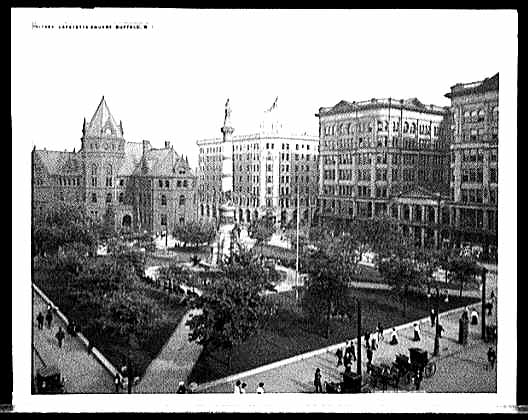

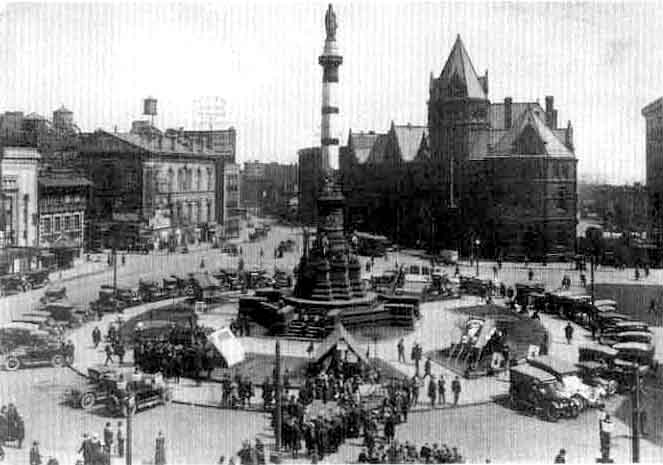

in Lafayette Square By Benjamin R. Maryniak  Lafayette Square in early 1889  1889 before reconstruction, but note that the Buffalo Public Library is finished  Lafayette Square c. 1904  Before WWI  Drawing by Ben Maryniak of "drum" bas-relief figures  Drawing by Ben Maryniak of "drum" bas-relief figures Deftly summarizing their function, a poet once described

monuments as "the hooks that hold generations together." To be sure, Civil

War veterans who comprised the Grand Army of the Republic had some less-than-grand

reasons for erecting bronze and stone memorials of the far-off war times -- they

were afraid of being left on the roadside, forgotten and impotent, as postwar America

surged toward its future and showed little concern for the past. But monuments were

also built to inform the public about the war when none of its survivors were left

alive to think and talk about it. There was also an intent to honor all of the country's

military, in keeping with those "mystic chords of memory" visualized by

Abraham Lincoln as stretching from battlefields to every American heart, and being

strummed "by the better angels of our nature." The first public meeting to discuss a Civil War monument for Lafayette Square

was held on April 14, 1866, but nothing much got accomplished until the Ladies

Union Monument Association was organized on July 2, 1874, headed by the wife

of former governor Horatio Seymour. Pressing resolutely on, the women soon raised

$12,000 in subscriptions and approved the design submitted by architect George

Kellar of Hartford CT. Compelled to take action during 1881 in view of the progress

made by Mrs. Seymour's ladies, the city government appropriated $45,000 for the project

and awarded a construction contract to the Mount Waldo Granite Company of Bangor,

Maine. Proposals for bronze sculptures (and the stone lady who topped

the column) by Caspar Buberl were eventually approved. The completed monument was standing in Lafayette Square before the last day of 1883, but dedication ceremonies had been set for the following year. The features of the monument still appear today as they did in 1883: A nameless stone lady, "emblematic of Buffalo," sits atop the 85-foot column. Eight-foot statues representing members of the infantry, cavalry, artillery, and navy surround the shaft, which itself is decorated with bronze symbols of the nation and state, the seal of Buffalo, and a "drum" showing over thirty bas-relief figures. The final half of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address appears below the "drum"

on the back of the monument and the message "in front," facing Main Street,

dedicates it to those who laid down their lives "in the war to maintain the

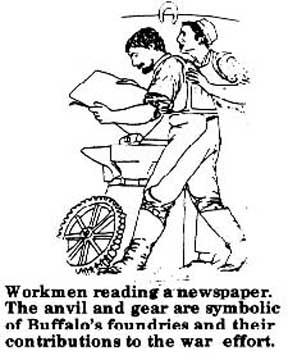

union for the cause of their country and of mankind." Also part of the bas-relief are soldiers, including a zouave and a drummer boy,

marching in reply to Lincoln's call. Two cavalrymen, one of them a bugler, tangle

with their mounts; the other trooper is doffing his hat to a woman as she cries into

her apron. A newsboy sells papers while a blacksmith and a baker read one. A group

of soldiers bid goodbye to their loved ones. The New York Department of the Grand Army held its semi-annual encampment at Buffalo

to coincide with the monument's dedication on July 4, 1884. In addition to a crew

regatta, horse races, and fireworks which took place on that day, a huge parade snaked

through the city. Assembling on West Eagle, the parade took Main to Seneca to Michigan

to Clinton to Washington to Lafayette, and then took Main to Allen to Delaware to

Niagara Square! The marchers than packed themselves into Court Street, between Niagara

Square and Lafayette Square, with all faces toward the new monument. Members of various

New York police and fire departments, elected officials, and civic organizations

joined seven brigades of Grand Army veterans in this long trek. Brevet Brigadier

General Wm. F Rogers, former colonel of the 21st NYV, Buffalo's first regiment to

leave for the Civil War, led the procession. Parties of veterans representing many

New York regiments carried their original colors. Not only was NY Governor Grover

Cleveland in attendance, but he was joined by Pennsylvania Governor John Hartranft,

who was a Medal of Honor recipient and former brigadier general in the Union army.

GAR Commander-in-Chief RB Beath was also on hand, as was GAR character "Corporal"

Tanner. A fierce thunderstorm broke out during the monument's dedication but General

Woodford still delivered his oration, followed by words from Rev Philos G Cook, who

had served as chaplain of the 94th NYV during the war. Despite this seemingly-auspicious start for the Lafayette Square monument, things

quickly started to go wrong. The column soon developed a Tower-of-Pisa-esque tilt.

The judgment of city inspectors was that the foundation had settled unevenly and

the entire monument would have to be dismantled and rebuilt. At least another forty

thousand dollars was spent to rebuild the monument on a sounder base during 1889.

It was found that the 1882 "time capsule" had been crushed and its contents

destroyed by water. Reconstruction worked out better for the monument than for the

North, however, and the rebuilt memorial stood about 15 feet higher on the base we

can see today. [See History - McDonnell & Sons / Stone Art Memorial Co. for information

on the company that renovated the monument.] |

|

Caspar Buberl Caspar Buberl, the sculptor who did the bas-relief "drum" around the monument, was born in Bohemia 1834, studied in Prague and Vienna, then came to the U.S. during 1854. By 1882, he had sculpted several well-received pieces and established a studio in NY City. He received a commission from the US Government to create a 1200-foot-long terra cotta frieze on the Pension Building in Washington DC (Judiciary Square, F Street between 4th and 5th Street NW) which showed hundreds of Civil War soldiers marching along. These figures are much like the ones on the Buffalo monument. The Pension Building was put up in 1884 and is still in DC. |

|

Parrott rifles are so named because of the rifling of the cannon barrel. The spiral cuts in the interior of the barrel added spin to the projectiles, which made them more accurate than smooth bore cannons. The projectile itself was the pointed shape of modern artillery shells, spelling the eventual end of cannonballs as ammunition. So these can accurately be called either rifles or cannons. The rifles and ammunition were both perfected by Robert Parrott, a former U.S. Army officer and, from 1836 to 1876, superintendent of the West Point Foundry, where the cannons were cast. By 1860, his design of the rifle was set. Its long barrel of cast iron had a tendency to blow up, so to help stabilize it, a wrought iron band was forged around the bottom, giving the rifle its distinct profile. It was still a dangerous piece to fire, but its accuracy made it the cannon preferred by the army and the navies of both sides in the Civil War. Buffalo’s Parrott rifles are 100-pound naval versions. Various sizes were cast but the 100-pounders could fire projectiles weighing up to 100 pounds as far as 7,800 yards and needed a crew of 17 sailors to load and fire them. By the 1870s, this cannon model was already obsolete since it was made for wooden warships and would not fit the new iron fleet. In the 1880s the Philadelphia Naval Yard offered cities its supply of surplus 100-pound Parrotts which had never been used in combat. Buffalo acquired 20 to 25 of them and probably put them in storage until suitable sites could be selected. In 1889 the foundation of Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Lafayette Square was rebuilt. As part of the work the square was redesigned and 10 of the Parrotts were placed in the space, two each on the four paths and two in front of the main steps. By 1897, in time for the huge Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) convention of Union Army veterans and their families, eight more were placed in Front Park where a large tent city reminiscent of their wartime bivouacs was set up. The cannons were mounted on what were called GAR carriages, elaborate cast iron frames that were not useful as firing bases but were strictly decorative. They soon became popular for people sit on for pictures, the selfies of the time. Another alteration of Lafayette Square in 1912-13 changed the square to a circle to accommodate an extension of Broadway to Main Street, and the cannons were removed. Four of them were placed on Colonial Circle and two were placed in the Great Meadow in Delaware Park, on either side of the memorial to Buffalo’s unknown soldiers of the War of 1812. The rest were probably sold for salvage. |