San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane - Table of Contents ............. Architecture Around the World

2002 and 2013 photos

Exterior

Church of Saint Charles at the Four Fountains

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

Via delle Quattro Fontane and Via del Quirinale, Rome, Italy

Fountains built:

1588 and 1593

Fountains style: Late Renaissance

San Carlo: Named after Saint Charles Borromeo.

Borromini's real name was Francesco Castelli. He worked under the name Borromini, it was said, as a sign of his reverence for St. Charles Borromeo, another Lombard.

San Carlo built:

1633-1641

San Carlo architect:

Francesco Borromini (1599-1667).

Borromini received the commission in 1634, under the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, whose palace was across the road. First church that Borromini built in Rome.

Although the whole complex was designed by Francesco Borromini, some parts of the work -- the façade and bell tower -- were actually completed by his nephew and heir, Bernardo Borromini, after Francesco committed suicide in 1667. Borromini had started the façade and tower only a few years earlier, so the Carlino represented both his first and his last architectural work.

San Carlo style:

Baroque

This church is considered by many architects and art historians as the most perfect of all Baroque structures.

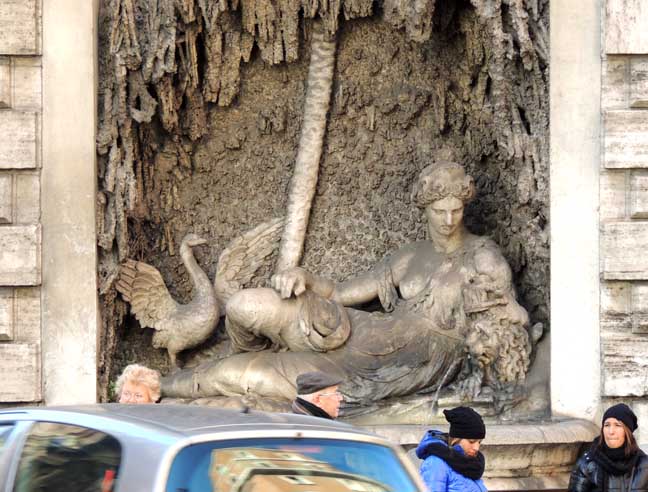

- Fountain - The Goddess Juno

- Fountain - The River Arno

- Fountain - The Goddess Diana

- Fountain - The River Tiber/ Church of Saint Charles at the Four Fountains

TEXT Beneath Illustrations

Goddess Juno  Juno. The Quattro Fontane (the Four

Fountains) is a group of four Late Renaissance fountains located at the

intersection of Via delle Quattro Fontane and Via del Quirinale in

Rome. They were commissioned by Pope Sixtus V and installed between

1588 and 1593.

The later Baroque church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, by

Francesco Borromini, is located near the fountains, and takes its name

from them.The figures of the four fountains represent the following:

Juno  Juno  Juno |

Arno  Arno  Arno |

Goddess Diana Diana  Diana. Note window above Diana (next photo below)  Diana  Diana |

| River Tiber Note balustrade . round medallion (photos below)  Tiber. Note top of building. San Carlo features columns (close-ups below). The church façade is in travertine and is integrated with that of the monastery. It also curves around the corner and incorporates the pre-existing fountain of the Arno River god. "[Borromini] sets his whole facade in serpentine motion forward and back, making a counterpoint of concave and convex on tow levels (note the sway of the cornices)

and emphasizes the sculptured effect with deeply recessed niches.

This facade is no longer the traditional , flat frontispiece that

defines a building's outer limits; it is a pulsating membrane inserted

between interior an exterior space, designed not to separate but to

provide a fluid transition between the two." - Gardner's Art Through the Ages, Tenth Edition, by Richard G. Tansey and Fred S. Kleiner. Harcourt Brace College Pub. 1996, p. 828.

Tiber  Tiber  Above Tiber fountain: Medallion depicting Mary, the mother of Jesus, with flanking ribbons. "Ave" means "hail," as in "Hail, Mary, full of grace..."  Baroque curves on window surround  Baroque serpentine motion. 3 facades  Two facades. The second, a narrow bay crowned with its own small tower, turns away from the main facade and, following the curve of the street, faces an intersection  Baroque serpentine motion |

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane San Carlo entrance. Four tall columns with their unusual capitals on which single acanthus leaves curl around crowns.  San Carlo: Baroque serpentine motion. Four tall columns with their unusual capitals on which single acanthus leaves curl around crowns.  San Carlo. Statues by Antonio Raggi. Center: San Carlo Borromeo, the patron saint of the church. Left and right: St. John of Matha and St. Felix of Valois, the founders of the Trinitarian Order.  San Carlo: Balustrade  San Carlo. Left pavilion: A small bell tower is topped by a pagoda-like roof  San Carlo. |

|

Borromini was trained as a mason, and, since he was

distantly related to Maderna, found work in a small way at St. Peter's when he went

to Rome at the age of fifteen. The same vehemence of approach and the same revolutionary disregard of conventions characterize Borromini's first important work, the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, begun in 1633. A new dynamism appears in the little church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, where Borromini goes well beyond any of his predecessors or contemporaries in the plastic handling of a building. Maderno's facades of Santa Susanna and St. Peter's are deeply sculptured, but they develop along straight, lateral planes. Borromini, perhaps thinking of Michelangelo's apse wall in St. Peter's, sets his whole facade in serpentine motion forward and back making a counterpoint of concave and convex on two levels (note the sway of the cornices), and emphasizes the sculptured effect with deeply recessed niches. This facade is no longer the traditional, flat frontispiece that defines a building's outer limits; it is a pulsating membrane inserted between interior and exterior space, designed not to separate but to provide a fluid transition between the two. This functional interrelation of the building and its environment is underlined by the curious fact that it has not one but two facades. The second, a narrow bay crowned with its own small tower, turns away from the main facade and, following the curve of the street, faces an intersection (The upper facade was completed seven years after Borromini's death, and we cannot be sure to what degree the present supplemented and complex structure reflects his original intention.) Sources:

|

|

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

are, however, two

churches where Borromini's full originality can be seen at its best:

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (the Romans call it San Carlino) and

Sant'Ivo della Sapienza.The problems Borromini was asked to solve in these two churches were widely different. San Carlino occupies a small, awkwardly shaped plot at a street corner; Sant'Ivo is part of a vast building complex and rises at one end of a spacious arcaded courtyard; but both reflect the same interest in expansive form, in energy expressed through the movement of the architecture rather than the profusion of detail. San Carlino is the earlier of the two, but already we see Borromini at his dazzling best. Begun in 1638, the church was consecrated in 1646, and it was unlike any other building in Rome. Because it stands at the corner of two narrow streets, any movement in the facade had to be restrained; clearly, the solution was to use the right curves to create a dramatic play of light and shadow. What Borromini did here, too, was to set up a series of oppositions, between lower and upper levels, between the center and the edges, between the tall columns and the smaller niches. Undulating gently, the facade swells out in the center; but then the doorway breaks into this convex movement as does the niche right above it with its statue of San Carlo Borromeo, the patron saint of the church. All this undulation, in turn, is firmly contained by the four tall columns with their unusual capitals on which single acanthus leaves curl around crowns. This undulating movement continues all the way up, and because so much is happening, we quite forget we are looking at a very small church squeezed into a plot barely big enough for itself, and one, which depends entirely on the interplay of geometric forms. And because this interplay is so rich, and so vigorous, a facade that should look mean and squeezed is imbued with almost awe-inspiring energy. As if all that were not enough, Borromini has prepared a few surprises for us. If we cross the street and look up, we see two small structures emerging from the roof. On the right, a small bell tower is topped by a pagoda-like roof; on the left a scalloped pavilion is topped by a roof that looks like the decreasing layers of a very large cake. In both cases, the forms are unusual and interesting; but one thing is certain: uniquely for a Roman Baroque church, Borromini has dispensed with the standard dome. Or so it seems. Walk into San Carlino and you find yourself in an oval space above which soars a vast and elaborate dome. Surging from what looks like an oval coronet of stylized strawberry leaves, its surface is decorated all over by circles, ovals, hexagons and crosses in high relief. There is nothing here but geometric figures; but because they fit so intricately into one another, they are more sumptuous than the most lavish sculptures. Of course, after a while, it becomes clear that this impossible dome is in fact placed within the oval base of the layer-cake pavilion: but that does not rob it of its magic. The ground plan of the church is just as fascinating. Basically oval, it is given life and movement by rounded extensions, while the main altar is topped by a half cupola whose dramatically foreshortened coffering makes it loom impressively large, an effect that is repeated on the two side chapels; and all is linked and kept orderly by a procession of giant columns. The minuscule cloister just to the right of the church is a good preparation for the next stage in Borromini's career. Here, in a tiny space, the architect has created the illusion of openness by designing a hexagonal arcade topped by a plain colonnade. |

Photos and their arrangement © 2002, 2013 Chuck LaChiusa