Joseph Dart - Table of Contents

![]()

Joseph Dart - Table of Contents

Joseph Dart

HISTORY Beneath Illustrations

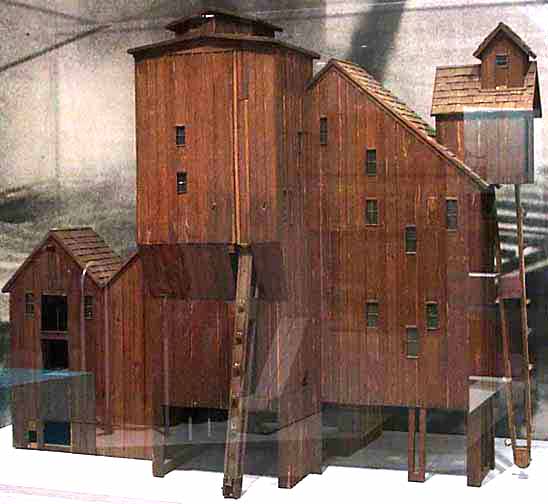

Source: Display at the Buffalo History Museum  Model of Joseph Dart's original wooden steam-powered grain elevator on display in the Buffalo History Museum Dart added a second marine leg in 1846 so that 2 different ships could be unloaded at the same time, one on the Buffalo River, one on the Evans Ship Canal.

The two towers - the "marine legs " - include a vertical conveyor belt made of leather or canvas and equipped with buckets. The conveyor could be canted outward from the leg and lowered directly into the hold of a waiting ship that was loaded with grain. The grain would be emptied - "elevated" - up this leg to a scale where it was weighed before being distributed to large storage bins. There, grain would be stored until sold. At sale time, the grain would be

drawn off through the bottom and raised again to the scale. Finally,

the grain "spouted" down into a waiting canal barge moored where the

arriving lake vessel had docked.

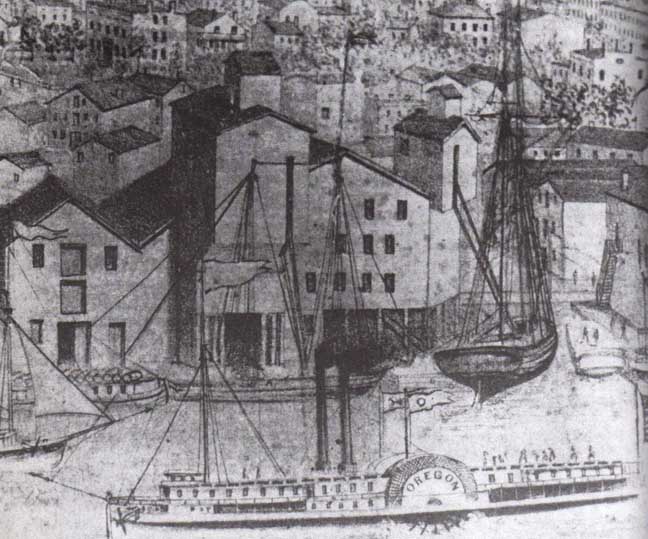

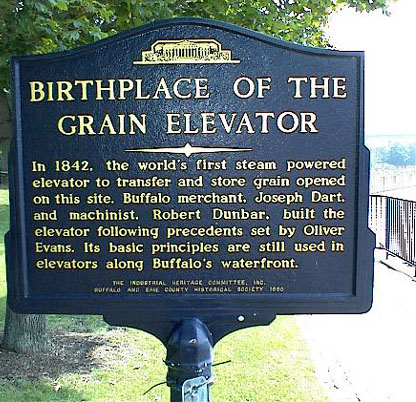

Moving conveyors were steam powered fueled by coal. The original grain elevator transfer and storage facility built by Joseph Dart and Robert Dunbar in 1842 stood near the present Vietnam Veterans Memorial in downtown Buffalo  Historical drawing. Note, at right, the marine leg lowered directly into the hold of a ship.  Photo courtesy of Chris Andrle Dart's stone marker in Forest Lawn Cemetery |

|

The text below is reprinted

from the application for landmark status for the Great Northern grain elevator (City of Buffalo approved 4/10/90)

In 1843 Joseph Dart of Buffalo solved the problem of handling the grain with the invention of his steam-powered elevator. Dart's bucket elevator raised grain from lake boats to built storage bins where it remained until being lowered for transshipment or for milling. The elevator had a storage capacity of 55,000 bushels. In a paper read before members of the Buffalo Historical Society in 1865, Joseph Dart paid tribute to his acquaintance, Oliver Evans, an American inventor and millwright who invented a gravity-fed grain mill with a bucket conveyor as the means for raising grain to storage bins at the top of the plant, where it would flow down under its own weight through the sequence of milling processes. Dart, in addition to creating the first steam transfer and storage elevator in the world, devised a means of lowering the bottom end of the bucket into the holds of the large vessels that brought grain across the Great Lakes or of the barges that moved it along the Erie Canal. This was a turning point in the industry, marking a shift from the manual labor of men on ladders to a mechanized system. Dart's pioneering effort was quickly and widely imitated. Less than fifteen years after his was built, there were ten grain elevators in operation near Buffalo Harbor. They had a storage capacity of 1.5 million bushels. By this time Buffalo had become the world's largest grain port, surpassing Odessa, Russia; London, England; and Rotterdam, Holland. Dart's elevator was built of wood. Plentiful in the Buffalo area, wood was used for construction of grain elevators for half a century. The earliest elevators were located on or near the water and served only lake or canal boats. Later materials included steel, concrete, tile and brick. Although the exterior arrangement often varied, the interior arrangement was always similar. "Engineering News" in 1898 noted:

|

|

(online August 2013)

Flour Milling Starts Slowly There was no milling industry in pioneer Buffalo - just the usual grist mills out in the country. But then the immigrants who had poured into the West began to seed the prairies with golden wheat. Before too many years, the grain trade on the Great Lakes expanded considerably. In 1829 Buffalo handled 7,975 bushels of flour and wheat. By 1830, just one year later, the combined shipments were 181,029 bushels.By the time the first grain elevator was put up in 1842, the flour and grain imports had soared to 3 million bushels! Joseph Dart was watching grain being unloaded at the Buffalo wharves one day in 1841. Slowly and laboriously the grain was cupped into buckets. I t was then carried on the backs of strong Irish dock workers into the warehouses to be weighed and recorded. Not more than 2,000 bushels a day could be moved out of a ship's hold when this age-old method was used. Joseph remembered the invention of a pioneer American miller, Oliver Evans, who had originated and patented a conveyor belt for use in grain milling. Not a hand touched the milled flour as it was transported on a leather belt revolving on pulleys from the millstones to the hopper box. Dart wondered why this device couldn't be adapted to the unloading and storing of grain at the jammed Buffalo piers. Amid the jeers of doubtful onlookers, Dart put up a building on Buffalo Creek. He constructed a large warehouse and installed a perpendicular conveyor belt fitted with buckets that could elevate the grain from the ship's hold to the storage house. This elevator was powered with a steam engine. He was then ready to transfer grain from the lake carriers to either the canal boats or to his storage bins. The innovation was an immediate success. The schooner, John S. Skinner, came in from Milan, Ohio and docked in the early afternoon. She was unloaded by Dart's system, took on a ballast of salt, and was out of the harbor before dark. She was able to make a return trip to Milan and transfer her second cargo at Buffalo before other ships, being emptied by the hand method, had finished unloading their first cargoes. The grain trade, with this automatic aid, was to advance Buffalo to the position of the leading grain center in America. |