Niagara Falls, ONT July 25, 1814

“Horatius at the Bridge” (1842)

Thomas Babington, Lord Macaulay

History and legend are full of battles at bridges. One story attributed

to one of Rome’s early heroes comes most likely from the latter source.

Around 510 BC Publius Horatius Cocles was said to have fought single

combats over the Tiber River against an Etruscan army, giving his

comrades behind him time to tear up the timbers of the Sublician

Bridge. He had two companions, but he stood alone at the last. Having

saved the city, “Horatius at the Bridge” breathed a quick prayer to

“Father Tiber” – a river personified as a spirit – dove in in full

armor, and managed to make it to shore.

One from history and precisely 1066 AD involves the stand made at

Stamford Bridge by a nameless Viking against an army under Harold

Godwinson, the last Saxon king. Possibly using a four-foot man-feller

called “the Dane Axe,” this determined giant may have dropped 40 Saxons

– a group of people not remembered as wimps – so that a mass of his

fellows camped on the other side of the river Derwent could ready

themselves for an orderly retreat. He may have been there yet but that

someone got into the water under him, stuck a lance up through the

bridge’s laths, and gave him a shiver in the privies that weakened him

enough to be overcome.

One pivotal bridge-battle that, except for our less heroic and

superstitious age, could have become as legendary as either of those

took place in Buffalo 200 years ago.

2

By late July 1814, the American Army of the Niagara had proved its

point. The clash at Lundy’s Lane had been some kind of a victory, but

probably that style best-described as Pyrrhic (“peer-ick”), meaning one

that costs you more than you can afford. [After bloodily prevailing

over a Roman army, Greek commander Pyrrhus famously declared, in rough

translation, “One more ‘win’ like that and I’m toast.”

Two of the three top American commanders, Jacob Brown and Winfield

Scott, had been wounded, the latter seriously enough to be withdrawn

from the war action. Having taken so many losses, the army’s fighting

strength was dented. No more sashaying about the Canadian Niagara for

this 2100-man outfit. In fact, within a few days of Lundy’s Lane, the

Americans withdrew all the way back to their only defensible Canadian

base, Fort Erie, licking wounds and digging in.

As long as they held an important fort that controlled water routes,

the British would keep their strength on the Niagara divided and make

no major moves into New York State. If the Americans at Fort Erie fell,

the disaster would quite likely have been followed by an invasion. Lest

that idea seem farfetched, 15,000 redcoats were at that moment on the

move out of Canada into the Hudson Valley. Had the Americans not won

the naval battle on Lake Champlain (September 11), destroyed the

British supply lines, and put the commanders in fear of falling into

the same trap the British had met at the Revolutionary Battle of

Saratoga (1777), that juggernaut would have driven a wedge down the

eastern part of the state and been having breakfast in Manhattan by

Halloween.

With failure at Fort Erie, the least anyone could expect was another

devastation of the American side. Fort Erie represented nothing less

than a fight for Buffalo, still smarting from its last acquaintance

with the Empire’s torch, tomahawk and sword. This was a high-stakes

game, and the odds were long.

The British and Canadian war effort was getting only stronger. Supplies

and reinforcements were coming in every day to the bases along the

Niagara peninsula. So many redcoats eventually encircled the Americans

that from a skycam it would have looked like there was a pink

constrictor around Fort Erie. The British set up camp about a mile

northwest of today’s Fort, fully out of cannon range.

But the British had given the Americans a week before putting the main

squeeze on Fort Erie. They’d been waiting to gather even more strength,

but in retrospect, this was a mistake. The Yanks used the interim well.

3

In 1814, Fort Erie was a far cry from a monument. An even simpler fort

of the same name (1764) had stood near the present one. It was a wooden

structure that was too often crumbled by lake ice from the massive

pileup that occurred at many a winter’s end at the in-end of the

Niagara. It’s fairly embarrassing when that happens to your fort. The

revised, five-pointed stone version we see today had been moved back

from the river and ringed with earth-mounds to stand up to cannon-fire.

The Fort itself had been incomplete at the start of the war and

occupied, abandoned and even hastily taken apart at least once by a

retreating force. This was no place upon which to bet the fortunes of a

region.

The bluecoats did their best to shape the compound before the Brits

appeared, putting in round-the-clock shifts under blazing heat with

little sleep. It was a race. Supplies came in from all over:

ammunition, rifles, and sabers from Fort Schlosser in Niagara Falls;

600 “solid shot” (cannonballs) from Sacketts Harbor; 25 barrels of

gunpowder from an arsenal at Batavia; and axes, shovels, horses, mules,

and food from Buffalo.

The Americans set up cannon batteries in the likeliest defensive

positions. At the extreme southern end of their position was Captain

Nathan Towson’s five-gun battery on the strange, ancient Snake Hill, a

site and spot that would make itself legendary in about two weeks. The

northern end was anchored by the stone fort itself and protected by the

two-gun Douglass battery. The middle of the American defenses was

secured by new earthworks, Captain Biddle’s three-gun mound and

Lieutenant Fontaine’s two-gun breastwork. The Niagara River did it all

for them on the east side.

The Americans also dug new trenches outside the fort and filled their

perimeter with nasties, including a fretful obstacle course called

abbattis (in the rhyme and rhythm of, “quick release”). Sort of an

inanimate porcupine, abbattis was the day’s version of razor-wire, a

man-made thornbush formed largely of small felled trees with sharpened

branches and festooned with prickers, sticks, arrows, flint shards, and

anything else that might sting an approaching foe. Abbattis was

particularly effective against night attacks, even serving as an

advance-warning system. (Upon a surprise entanglement with abbattis,

even the most stoic attackers tended to yodel.)

This was all well and good for digging in and ducking cannon, but Fort

Erie was too far from the river to protect its supply lines down to the

Niagara. The most significant project the Americans undertook was to

build a defensive ramp down to the riverside so that men, munitions,

and other supplies could get to them safely. This was 700 yards long,

and the eventual construction would be seven feet high and eighteen

feet thick. From the ditch below – doubtless filled with more abbattis

– the climb to the top would be about 14 feet, with some grim defenders

waiting. Attacking this formation would be no walk in the park. It was

also a lot of contested real estate to patrol. Any way you look at it,

the Americans were going to be spread thin.

By the last day of July the Americans’ earthy fortifications, thus

their supply lines, extended out from the Fort to the edge of the

Niagara River. As long as this situation stood, the Americans could

camp out at Fort Erie indefinitely. The next move would come from the

redcoats. Right on cue, Major General Gordon Drummond, Lieutenant

Governor of Upper Canada, pulled up before the fort, probably on August

1. Time to dance.

4

In the window between Lundy’s Lane and the war’s next action, something

interesting happened in Buffalo. It involved one of Buffalo’s heroes,

the famous Seneca Farmer’s Brother (1730?-1815).

The model of the warrior-statesman, Farmer’s Brother was a true Seneca,

loyal to a people, not a concept or a nation. Farmer’s Brother fought

where the Great Hill people fought, which took him to an adventurous

career in a series of wars. Farmer’s Brother may have fought for the

French against the Empire, the Empire against the Americans, and then

the Americans against the Empire. The ever-dramatic historian Crisfield

Johnson reported him leading the Seneca “through many a carnival of

blood.” He might have been at the Devil’s Hole in 1763. He might have

been at the 1778 massacres of Wyoming and Cherry Valley. Still, in all

three years of the 1812 War, Farmer’s Brother was one of Western New

York’s staunchest defenders and a friend to many individuals and

families in Buffalo. He might have been in his 80s at the time of the

1812 war, though he was still described as remarkably fit, even

powerful and imposing. They don’t make them like that any more.

One of his remarkable episodes came during the spring of 1813. When the

Seneca turned out for the American cause, a large body of Native

Americans camped in the woods near Buffalo, which then crept up to well

within today’s city limits. One night several of them got away from the

main camp and tried to break into the Algin family home around the spot

of today’s North and Linwood. These Native renegades were not the only

parties known occasionally to use the homes and farms of Buffalo’s

citizens as all-night delis and liquor stores. The widely-despised

state militia did so much of it in the winter of 1812-1813 that the

citizens formed vigilante groups in response. The desperadoes besieging

the Algin clan found the doors and windows barred – settler-era homes

could be little forts – so they climbed to the roof and started tearing

it up to get in from above. The smallest of the Algin boys squeezed out

an escape portal and ran through the dark woods for Farmer’s Brother,

then sleeping with his mates not far off. With the little lad’s hand in

one of his own and a tomahawk in the other, Farmer’s Brother approached

the scene. One glimpse of his formidable form stalking through the

trees sent the thugs running. As with the great Shawnee Tecumseh

(1768-1814), respect flowed out of Farmer’s Brother like a psychic

force, with the effect of an electric field that people could sense

before seeing him. The big chief spent the rest of the night at the

family’s fireside.

In the turbulent summer of 1814, each of the Niagara Frontier’s

opponents was curious to know what the other was doing. Both had Native

American allies, scouts and spies. On the last day of July, a man of

the British-allied Chippawa nation crossed the river from Fort Erie and

fell in among the pro-American Seneca in Buffalo. He claimed to be a

deserter, but the Seneca weren’t too sure he wasn’t just a spy poking

around for information. A party of them shared the flask with him all

the same. Before long everybody was telling war stories.

The Seneca couldn’t help but relive the butt-kicking they’d given the

British, Canadians and Native allies in the woods at the July 5, 1814,

Battle of Chippawa, Ontario. For his own part, the Chippawa brave

recounted all the Americans and Seneca he’d killed on the same day.

When asked to name just one of them, he mentioned the Seneca Chief

Twenty Canoes, lifelong friend of Farmer’s Brother then yards away from

the party.

Landon’s Mansion House was a tavern on the southwest corner of today’s

Exchange and Washington streets. It was then being used as a hospital.

Convalescing there was Captain William Jenkins Worth (1794-1849), a

dashing young member of Winfield Scott’s staff destined to be a big

man. (Ever hear of Fort Worth, Texas? Worth Square in New York City?)

On the day in question, the 20-year-old was not expected to survive a

grisly leg wound, courtesy of a delivery of British grapeshot at

Lundy’s Lane a week before. Worth had become a particular favorite of

the Senecas, in particular Farmer’s Brother, who watched long hours by

his bedside and happened to be with his young friend when word came of

the braggart who’d killed an old one.

Somewhere east of Main Street where it meets today’s Swan, Farmer’s

Brother walked right up to the Chippawa and set a few items before him.

“A hero like you deserves a reward,” he said. “I’ve got just the thing.

I’ve got a knife, a tomahawk, and a gun here. Which would you like?”

The Chippawa took a shine to the gun and expressed as much. Farmer’s

Brother picked it up and plugged him between the eyes. Four young

Seneca carted off the carcass, dumped it in the nearby woods, and left

it to be eaten by animals. In the spring of 1820, soon-to-be Buffalo

mayor Orlando Allen found a skull with a hole in it near the crossing

of Seneca and Chicago streets. It was presumed to be that of the

whiskey-tongued Chippawa.

5

In every part of the world that ever had them, walled forts were vital

for controlling territory. This maxim held even into the early 19th

century in America. If you didn’t hold the fort you hadn’t won the

ground. Forts were usually positioned at choke points of transportation

and trade: mountain passes, river mouths and major trails. A small,

beaten foe could often hold that spot against a mighty army and rush

out to gouge it at the worst possible time.

In the European Middle Ages it was generally figured that every man

behind a wall was worth ten on the other side of it. Even then, holding

a fort against a siege was no latchkey operation, and the development

of projectile weapons, particularly cannon, shrank both the defender’s

edge and the majesty of a fort.

By the late summer of 1814 those picturesque castle-walls were gone.

(Cannon would have turned Camelot into a sandbox.) Forts kept such low

profiles that, from a distance, they were innocuous piles of dirt

surrounding solid one-and-two-story buildings. A charging army was

discouraged from running right over them only by trenches, obstacles

(like that blasted abbattis), and fire from the defenders’ musket and

cannon.

British commander Gordon Drummond (inset) had come to Fort Erie with

5350 friends, almost double the foes he faced and plenty enough to win

an open battle; but open battle this wasn’t. This was an outright siege.

Sir Gordon had a couple options. Were siege warfare likened to

assassination, there are several ways to knock off an opponent. The

most obvious is Plan A – attacking. It’s often tried first

perfunctorily to see if something gives, but it’s head-butting. It

usually hurts the attacker a lot more.

A hunkered-down defender has a second enemy, the simple basics of life:

food, water, and other materials. Plan B has always been just to cut

off a fort’s supply lines and wait, what might be considered starving

the defender out. That plan wouldn’t work if the defender was

well-enough stocked or could resupply himself. Unless something

disrupted that ramp-to-the-water system at Fort Erie, Plan B was going

to flop. And one thing that isn’t always remembered in many historic

recountings of sieges is that the besieger is often under some of the

same pressure, especially in Western New York on the verge of its dread

winter.

“Here let them lie/Till famine and the ague eat them up,” laughs

MacBeth at the English round his castle, and it was no joke. It’s

always dangerous for armies to sit still very long, and the vast

numbers needed to besiege a fort can be in that sense a disadvantage.

Siege warfare has often developed into a race to see which side would

run out of the necessities – or fall victim to a plague (MacBeth’s

ague) – first. If the British were to win at Fort Erie before the snow

set in, something was going to have to crack.

Another figurative tactic might be Plan C, basically giving Plan B a

nudge. If you can’t stop something from coming in when it arrives, stop

it from leaving where it was in the first place. It was choking off the

enemy’s lifeline at its source. This is what General Drummond set out

to do.

6

The Americans at Fort Erie were getting most of their deliveries from a

base and docks at Black Rock, the old cousin of Buffalo proper that lay

along the Niagara just south of the Scajaquada Creek. It’s well

sheltered from the west by Squaw Island. While crossing the open river

to and from Fort Erie, the American supply boats were getting

protection from the batteries of riverside cannon. Someone who could

sweep down alongside the Niagara from the north with a bit of force

could have destroyed the naval base and its docks, knocked out all the

cannon on the river, and blasted all the way to Buffalo. Under the

right circumstances it wouldn’t have taken much to do it. Almost all

the American strength on the frontier was off holding onto Fort Erie.

But for the attacker coming in on Buffalo from the north, the only

reasonable direction as things stood in August 1814, there were

roadblocks.

While someone driving on the 190 along the Niagara today might never

notice, 200 years ago any traveler would have observed that Western New

York has a lot of creeks. Some big ones feed into the north-flowing

Niagara, and they are barriers to anyone who hopes to move in numbers,

with baggage, or in force. You can only cross them in certain places.

The Scajaquada is the one cutting across the landscape north of Buffalo.

The Scajaquada has never been a hazardous creek, but as far as an

attacker was concerned, it was just about unfordable near the Niagara.

Wading across the neck-high water and keeping one’s powder dry would

have been a tall order even for able young soldiers. Climbing the

steep, slick banks, one was likely to take a ball or a bayonet if there

were determined defenders. Wagons, cannon... forget it. One needed a

bridge. The only one over the Scajaquada Creek substantial enough to

hold a passing army was about where today’s Grant Street crosses the

creek. This bottleneck above the American supply depot would have been

Buffalo’s northern defense point.

Buffalo residents had formed a small militia to patrol this vital area,

but they were day watchmen. They weren’t strong enough to repel a

serious attack, anyway. Every twilight a battalion of regular soldiers

was sent across the Niagara from Fort Erie to defend the bridge. Every

next morning those men returned to the Fort and hiked by that 700-foot

ramp from the river in safety. A British sneak attack was always

possible during the day, but everybody would spot it as it crossed the

river, and American reinforcements from Fort Erie would be only a few

minutes behind them. The window of opportunity was dawn or dusk.

7

Throughout the dark hours of August 2 and 3, the British stealthily

landed troops north of the Scajaquada Creek, where they massed until an

hour before sunrise. They were under the overall command of British

Colonel John Tucker of the 41st, another of the characters of the local

war.

Tucker’s own men referred to him as “Brigadier Shindy,” which in the

lingo of the day might have meant something like “Colonel Chaos.” They

didn’t address him as that, though. A little like the sobriquet “Smoke”

assigned with rueful respect to stock car racer/NASCAR owner Tony

Stewart, it suggested that the bearer of it was prone to outbursts. One

senses that Tucker’s, unlike Stewart’s, were directed at social or

political inferiors who aired any suggestion that he might be fallible.

This force was accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel William Drummond

(1779-1814), another Scots-English fire-breather and the nephew of high

commander Gordon Drummond. These guys had plenty of force to do the job

– up to 1700 redcoats – which was pretty close to the size of the crew

that had taken down Buffalo seven months before. They had also arrived

at the only place and time they could have to escape detection, but

they were on the wrong side of the Scajaquada. To get at their targets

– the supply depot, the docks and the cannon batteries – they would

have to use the bridge nearest the Niagara that everyone was keeping an

eye on.

Tucker’s American counterpart was Major Lodowick Morgan, a Marylander

in charge of protecting the American base from just this possibility.

Morgan was a sharpie. Anticipating night attacks, Morgan removed the

planks from the southern end of the bridge every dusk, making it

impassable. Every morning he put them back so the citizens of Buffalo

could use it. This partial dismantlement of the bridge was not only an

effort-saving maneuver, it was a virtual booby-trap for a dim-light

attacker.

Though it would have cost you to have told him so, Tucker hadn’t done a

very good job of covering up his intentions once on American soil. The

Americans had suckered him in, anyway. Morgan’s men had done their

sabotage at the bridge unbeknownst to the British, slunk off like they

were retreating in the full view of some scouts, took a breakfast

break– doubtless a brigade-sized takeout order of Egg-McWhupass – snuck

back through the cover and spread out along the creek. The British were

immediately spotted as they started moving in. How could they not be?

Tucker came right up to the bridge with a batch of redcoats and just

stood there looking at it as the Americans opened fire. Once again

citizens of Buffalo would awake to percussion, not knowing whether

their city, just beginning to be rebuilt, would be burned to ash once

again.

Not suspecting that the bridge could be booby-trapped, Tucker’s first

idea was to just run across it. He had a squad of his men launch

another of their famous bayonet-rushes, supported by gunfire from the

heavy trees and foliage along the creek. Lodowick Morgan may have had

as few as 250 men, but he quickly turned this move into a nightmare for

the British.

Under the best of circumstances these charges were costly if they did

not quickly disperse or engage the enemy; but in this case many

Redcoats fell through the sabotaged bridge, and others piled up and

made fat targets once the picture cleared. Dozens of British were shot

as they floundered in the creek or in their crimson logjam at the far

end. And the Americans shot true.

These professional soldiers of the Army of the Niagara were

supplemented by up to 80 volunteers from Kentucky, some of the

straightest shooters the smooth-bore (unrifled barrel) age had.

(Without the “rifled” – spiral-grooved – barrel, that little black ball

could start freelancing at only a few dozen yards.)

These “Kentucky Riflemen” so proverbial in the 19th century had had

their dander up against the Empire ever since the incident remembered

as “the Raisin River Massacre.” The January 1813 Battle of Frenchtown

(about 30 miles south of Detroit) was a bad loss for the Americans, and

up to 100 wounded POWs were massacred by British-allied Native

Americans. A number of them had been Kentuckians, and all the rest of

the war the Bluegrass boys were gunning for the British and especially

their Native allies. It sounds as if the whole state enlisted, and its

migrant sons developed a reputation for both wildness and pugnacity.

These Kentuckians were “perhaps the best materials for forming an army

the world has ever possessed,” wrote William Henry Harrison. “But no

equal number of men was ever collected who knew so little of military

discipline.” The future president and victor at Tippecanoe furthermore

observed, “They appear to think that valor alone can accomplish

anything… Such temerity... is scarcely less fatal than cowardice.” Ol’

Tippecanoe had his issues with their focus, but these Kentuckians came

in mighty handy at the upcoming Battle of New Orleans later in the war

– and at Scajaquada.

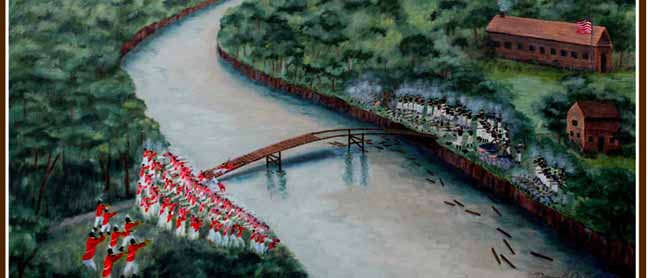

At least two more British charges on the bridge were turned away by the

outnumbered Americans (see lead image). Even Brigadier Shindy conceded

they were stymied. They pulled back from the fray for a bit of

stock-taking. Though badly stung, the redcoats were still well strong

enough to win the day. How they gnashed their teeth to close with these

Americans! Another plan was needed. Tucker picked the one that would

have occurred to any of us: test a different point.

The British sent a chunk of their force a ways east along the north

side of the creek and tried to cross upstream of Morgan’s position. The

spot is uncertain today, but it would have been about a half mile east

of Grant Street, possibly in today’s Forest Lawn Cemetery. Had they

been successful, one more of those bayonet rushes would have come

charging in on the Americans by the bridge from their right and on

their own side, and the day’d have ended up differently. But Lodowick

Morgan had anticipated even that move. He had sent several dozen of his

Buffalo militiamen and Kentucky riflemen to shadow the British

flankers. When they started their crossing they got another dose of the

medicine they’d been prescribed downstream. They backed down at neither

point. Charge, die and regroup; charge, die and regroup…

Artist: Doreen Deboth

At the first caress of Homer’s “rosy-fingered dawn,” the battle was at

its deadliest. Once-secure sniping-spots came into plainer sight every

minute, often too late for the sniper. The clash continued well into

mid morning. On at least one occasion the British commander ordered

some of his men to attempt to fix the bridge so others behind them

could cross, all the while under fire from the Kentucky riflemen. The

work was so inefficient and the toll so fearful that they broke off the

maneuver. The redcoats performed admirably under the conditions,

though. Even the kids from ol’ Caintuck were impressed.

At last Tucker retreated to the north, found his boats, and headed back

to the Canadian shore – greatly understating his losses for posterity,

it would seem. British casualties are still uncertain, though

calculated in the scores. There were also surrenders and desertions by

the handful. Even the killed are in dispute. So many British were shot

in the water that the dead or wounded often drifted away from the

battle sites into the Niagara and were probably on their way over the

Falls within an hour. Witnesses reported the creek flowing red with

redcoats.

Old-time sources often refer to this clash as “The Battle of Conjockety

(sometimes Conjocta or Kenjockety or Conjuncta) Creek” after one of the

Scajaquada’s only-slightly-easier-to-spell alter names. Major Lodowick

Morgan would be remembered as “The Hero of Conjockety.” His cool

tactics and quick decisions had won the day. A new American superstar

was born. They were talking about him in Washington.

The American losses had been slight. Even more important for the

Americans than the direct victory was the psychological toll among the

British/Canadian ranks. In the preceding month the Empire had taken

some bloody hits. After this battle and during the coming siege of Fort

Erie, morale would slide and desertions rise. This might have been the

first real motivational gut-check on the other side of the Niagara.

For some reason the Battle of Scajaquada Bridge is often overlooked or

diminished. Some call it a skirmish, this two-and-a-half hour clash in

which between 1500 and 2700 men tried to kill each other. Although a

clear U.S. victory and the one absolute clobbering of the summer, it

had titanic bookends. Grander battles were to come, and soon.

8

While Tucker’s co-commander William Drummond was said to have delivered

comments that made his uncle Sir Gordon furious with Brigadier Shindy,

the official report blamed the failure at Scajaquada on Tucker’s men,

who “displayed an unpardonable degree of unsteadiness.”

“The indignation excited in the mind of the Lieutenant-General… will

not permit him to expiate on a subject so unmilitary and disgraceful,”

Drummond’s General Order declares. “It is the duty of all officers to

punish with death on the spot any man under their command who may be

found guilty of misbehavior in front of the enemy… Crouching, ducking,

or laying down when advancing under fire are bad habits and must be

corrected.” Dodging a bullet is misbehavior? No wonder there were

desertions.

Drummond’s reaction could seem mind-boggling today, even inhuman. I

agree that it looks detached. Drummond was not the only tone-deaf

British commander, but they were not all like him, in general or on the

Niagara. Prominent local-war figures like Isaac Brock, James

Fitzgibbon, and Cecil Bisshopp were revered for their humanity. In

those commanders who seem harsh to us today, the cause was not just a

lack of compassion. It was largely an aspect of cultural and military

philosophy that some commanders bought into.

It was truly believed at the time that on and off the battlefield,

British character was the difference-maker in the success of the

Empire. The tactic that most directly expressed this character was the

unflinching march into danger at the tipping point of a battle so as to

attain a military objective. A few in the forefront would drop at

first, but that was fated, anyway–it’s battle; and it would save more

British lives in the end. Then the enemy would quail, the defenses

would break, the day would be won, and the losses would be repaid

tenfold. It was thought that any slack given to the soldiers might cost

them the winning edge. It would have been hard to argue these

commanders out of their strategy. As far as the British could tell, it

had worked for centuries, at least in the age of slow-firing,

wild-shooting rifles.

Sir Gordon Drummond saw Scajaquada Creek as a setback. It was not a

disaster. The Empire replaced the men he lost in a week. What it could

not replace was the strategic defeat this clash had represented. There

was going to be no easy way out with Fort Erie. Back to the head-butt:

the seige.

9

We’ve met Shadrach Byfield a couple times in this series. He’s the

redcoat from Wiltshire, England whose slightly dizzy memoirs have left

us such dramatic visual images of some Niagara-region wartime events.

As one of the grunts, Byfield didn’t always know where he was or why he

was being sent there. He messes a few things up. Still, Byfield

remembered what he saw.

This Byfield was a survivor. Of the 110 men of his original 41st

Regiment who took Detroit in 1812, less than 15 were left in it by

early August, 1814, and most of them had been wounded at least once.

Byfield himself dodged death at the River Raisin; survived the siege at

Fort Meigs; escaped from the ditch after the failed attack on Fort

Stephenson; was one of the few who ducked William Henry Harrison’s

dragnet after the Battle of the Thames; joined the bloody night-raid

that took Fort Niagara; and stormed the hill at Lundy’s Lane without

getting a scratch.

Byfield’s luck ran out at the Battle of Scajaquada Bridge. A

black-powder ball from someone on the American side – maybe one a’ them

Kentuckians–plugged him in the right arm just below the elbow. Taken

back with the wounded to the Canadian side, Byfield struggled for days

at the hospital in Fort George and eventually lost the arm.

When he came to, Byfield was enraged to hear that his truant limb had

been tossed onto a dung heap. He went out to the unsavory pile and

looked through it until he found an arm he was sure was his. At this

point he got some lumber, had a tiny coffin made, and gave his missing

limb a Christian ceremony and burial. While Byfield’s rite might seem a

little precious to us now, he’s not the only one who gave such

treatment to a missing limb. Amputation was so common in the Niagara

war that a full spectrum of reactions was to be understood.