Dread seemed to forbid his advance and Shame to forestall his retreat. - John Norton

Niagara Falls, Ontario | July 25, 1814

1

"American Infantry Attacks at Lundy’s Lane." Painting by Alonzo Chappel in 1859.

Source: Wikipedia – public domain

"American Infantry Attacks at Lundy’s Lane." Painting by Alonzo Chappel in 1859.

Source: Wikipedia – public domain

July 1814 had been a good month for the U.S. The American Army of the

Niagara had been on the Canadian side only a few weeks, and victories

at Fort Erie and Chippawa Creek seemed to announce the turning of a

tide in the American military and in the national position in the war.

With that single victory at Chippawa, its commanders–Major General

Jacob Brown and Brigadier Generals Winfield Scott and Eleazar

Ripley–had restored some of the reputation of the American Army as a

fighting force and secured their own legacies as commanders. As we all

know, though, things are not always as they look. The American force

walked a razor’s edge, and everybody knew it. A single slip in their

planning would mean disaster as sure as a slide into the Falls. That

mass of water-energy they could see and hear below them was symbolic.

Some of the Americans’ problems were their own fault. Camping out in

enemy territory has never been uncomplicated, but some pro-American

forces did something real stupid.

To this point in the 1812 war, the Canadians had not been truly roused.

In fact, at the start of the conflict, the folk on the west side of the

Niagara had been reasonably apathetic. Canada wasn’t even a nation at

that point. Canada was the occasional name for the little-developed and

less populated part of eastern North America on the other side of the

water-barriers: the St. Lawrence, the Niagara and the Great Lakes. It

was the Empire’s part of North America, and by 1812 a good many of its

occupants were reevalutating the choice of masters the generation

before them had made. This war came along and unified them. In some

cases, it even incensed them.

The December 1813 burning of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) had riled the

occupants of Canada, particularly those in Ontario province, but they

seem to have felt that scores had been quickly settled. I agree. The

Americans suffered a tenfold payback within weeks. Incidents from this

second occupation set everything on fire again.

On July 18, some state militia and Native allies on a foraging mission

were looking for supplies at the village of St. David’s just west of

Queenston. They came under a bit of sniper fire from some members of

the 1st Lincoln Militia, a Canadian outfit with quite a track record in

this war. They went ballistic. They herded the villagers out and burned

all 40 homes and businesses. To the Canadians, this was Newark all over

again. While this was the poster-child incident for renewed outrage, it

was not the only one like it.

Any sympathy the Americans could have expected from fellow white North

American English-speakers on the other side of the Niagara had turned

to fury. As a result of St. David’s, the only safe place in Ontario for

an American was in the middle of of a U.S. Army formation or perhaps

inside a fort protected by it. Pickets–scouting parties–were harassed

by Canadian militia and volunteers, sentries disappeared in the night,

and kids and little old ladies spied on American troop movements for

the British. St. David’s was the grounds for a new resurgence of

atrocities by the Empire. Even the British burning of Washington, D.C.

a month later was to be blamed partly on St. David’s.

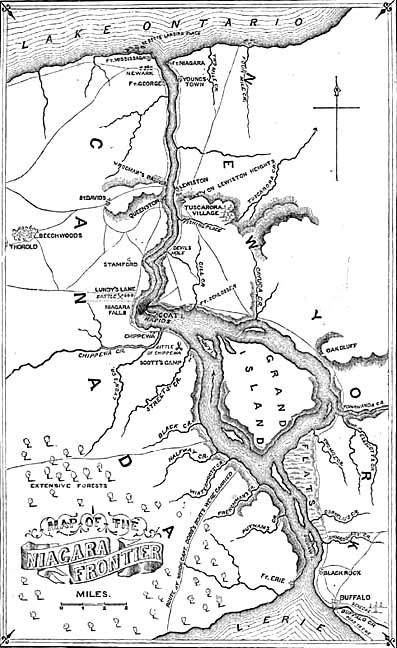

Some of the American problems were based on naval power, or their lack

thereof. In the rugged, densely-wooded northeast, water travel was the

only way to go, at least before the railroad and the I-90. It was a big

deal in military senses, too, and the British had the edge. They ruled

Lake Ontario and were constantly reinforcing their forts and armies on

the Niagara.

Sir James Yeo

Sir James Yeo

Source: Wikipedia – public domain

The U.S. had a bit of a naval presence on Lake Ontario, and it could

have pressured supply and reinforcement lines and otherwise stressed

the British war effort from the north and east. A couple of times Brown

called for U.S. Commodore Isaac Chauncey to pull his fleet out of

Sackett’s Harbor and do just that, even if only as a diversion. (Just

sail out and look tough, for God’s sake!) Chauncey, though, was

determined not to make a single move till he had put together a fleet

guaranteed to top his equally-cautious opposite number, British Admiral

Sir James Yeo . Up in Kingston, Yeo (who in one of his portraits

bore a startling facial resemblance to 2004 American presidential

candidate John Kerry) was building ships just as fast. (Their

woodworking frenzy was styled, “The Battle of the Carpenters.”) The

never-touching tango between these two, Chauncey and Yeo, was one of

the frustrating sidelights to the local war. (U.S. General Winfield

Scott called them, “heroes of defeat.”) Yeo might have been ducking a

fight, but at least his ships were sailing. The lack of naval pressure

on British-held forts like George and Niagara severely limited U.S.

Army General Brown’s tactics on the Niagara. It dictated where he could

go, what he could attack, and how much help he’d get. It also put a big

hurt on his supply lines.

Armies need to be constantly resupplied with food, weapons and

medicine. Even the smallest such mission to reinforce or provision

Brown’s American force was dangerous and costly. The Empire’s

skirmishers were masters at badgering supply missions, and force had to

be committed to guarding their launch- and landing sites. More badly

needed manpower was devoted to rowing small boats across the river

above the Falls from Buffalo and below them from Fort Schlosser.

(Schlosser was a blockhouse built in 1760 near today’s Niagara Falls.

It was located near the the spot of the current water intakes for the

New York Power Authority just off the Robert Moses Parkway. The Old

Stone Chimney we still see was once part of it.)

One gigantic fixed problem for the Americans was a ticking time bomb on

their side of the river: Fort George, the power-base on the Niagara

Peninsula. The British still held it, and from it Major General Phineas

Riall could sashay out with his army, shadow the U.S. force on the

Niagara, pounce if he saw an opening, and scurry back and duck the

fallout. Behind the bulwarks, walls and trenches he and his garrison

were safe, since the cannon big enough to worry them could only be

brought near them on ships. (See earlier references to the no-show

American Commodore Chauncey.) The British and their allies could play

stall-ball, and their orders were to do just that.

To add to that, British land power in the region was growing. Now that

Napoleon was done for and the massive European wars were over, those

hardened, veteran redcoat armies could be spared to come to America,

and nobody could do anything to stop them crossing the Atlantic. If the

U.S. force on this side of the Niagara couldn’t do something quickly to

shut up the local British bases–ports and forts–or choke the avenues to

and from them, it was going to be December 1813 all over again, and

maybe a lot worse. Soon the redcoat force on the Niagara would be four

times what it had been when it had torched the American side, including

Buffalo. Not even an invasion of New York State was out of the

question. In short, the U.S. Army of the Niagara had a single option:

fight and win. Soon.

As for the British, their high command still weren’t convinced that the

Americans could fight. It was as if they presumed the U.S. had lost its

national character after the generation of men and women who had won

the war of the Revolution. The first two years of the 1812 war had done

little to incline them otherwise. The few wins the U.S. had had against

them could be attributed to favorable circumstances and overwhelming

force, not tough soldiers and savvy commanders. The one that couldn’t,

the recent win at Chippawa, might still be regarded as a fluke. But the

British high command had learned not to take chances.

Three weeks in July passed in a game of bluffing chess. Brown shuttled

American troops up and down the Canadian side of the Niagara, hoping to

goad British Major General Phineas Riall into an open fight. No dice.

He came out, but he didn’t put out.

It was during this period that Winfield Scott had an adventure.

Reconnoitering outside Fort George, he heard the familiar chug of a

British cannon and spotted a cannonball on its way toward him. You

really could see those things in flight or bounding like stony soccer

balls over the landscape. Scott held his sword to the horizon, made

some quick calculations, and spurred his horse to a sidestep. The

missile dug a divot in the exact spot he had left.

Riall’s Native allies and Canadian militia attacked the American supply

lines continually, and the skirmishes were numerous. By July 24th,

Brown had to pull his camp back south towards Chippewa to be closer to

his supply base above, or south of, the Falls. During this relocation

an incident took place that brought two of the local war’s characters

face to face.

2

Since the last time the Americans had come by Queenston in force, a

troop of truculent Canadians and Native allies had reoccupied the

heights above the village. They were going to be a thorn that would

gouge the side of a slow-moving army as it passed. General Brown called

on some of his best skirmishers–Peter Porter’s militia and a mounted

troop of Canadian Volunteers under Joseph Willcocks–and ordered them to

clear the heights. The roving fight took most of the day of July 24 and

ended with members of the British Indian Department under Captain

William Johnson Kerr (1787-1845) holed up in a farmhouse and surrounded

by Willcocks and some of his Volunteers. Both figures are interesting.

Publisher, soldier, politician and rebel, displaced Canadian “King Joe”

Willcocks is still remembered as Canada’s national traitor. A born

Dubliner, he might have had his dander up against the British as a

factor of his DNA. By 1800–at the age of 17–he was in York (Toronto),

Ontario, and in politics by the time he was 21. One of his York bosses

described Willcocks as “lacking a sufficiency of brains to bait a mouse

trap.” (A handsome, dark-haired man, he screwed up his first

appointment there by putting the moves on his patron’s sister–rich,

homely and twice his age.)

By 1807 Willcocks was on the Niagara and publishing a rebellious paper,

The Upper Canada Guardian; or The Freeman’s Journal. He’d also had his

first brush with the Canadian establishment, the Empire’s political arm

in the Americas. In those days, an appointed body, the Executive

Council, controlled who got to own land and who didn’t. Not all its

decisions were unbiased. Willcocks and his associates objected to this

system, as did enough other Canadians to lead to an outright

rebellion–the Patriot’s War–by 1837.

Still, Willcocks was loyal to British hero Isaac Brock and the

British-Canadian war effort at the start. Willcocks claimed to have

been fighting for the Crown at Queenston Heights. The turning-point for

Willcocks came after Brock was killed and civil liberties–including the

right to any form of dissent–were reigned in. Willcocks and his

dragoons (mounted skirmisher-scouts) offered their services to the

Americans in the summer of 1813.

In the American cause in 1812 they saw an ally against an Empire not

known for second-guessing its decisions and its British-Canadian

government arm that seemed to them despotic. The Canadian Volunteers

were fighting their own liberation war. Their resentment of an

“imperialist” power would be praised in other times and circumstances.

While these Volunteers were good fighters, some of Willcocks’ decisions

did as much harm as good to the American cause. These Volunteers were

responsible for many of the depredations that offended the British and

Canadians. Rightly called “a firebrand,” Willcocks arm-twisted American

General George McClure to order the burning of Newark in December 1813.

To be trapped in a Queenston farmhouse by this loose cannon had to be

embarrassing, to say the least, for Kerr.

Part-Mohawk paramilitary William Johnson Kerr was the grandson of Sir

William Johnson (1715-1774), the British Superintendent of Indian

Affairs. An immensely influential Irish-born Brit with a thing for

Mohawk women, Sir William was not definitively the godfather of

hip-hop, but it’s been estimated that he was the baby-daddy to 100

children, including the mother of his eventual grandson. Another

illustrious Canadian, William Hamilton Merritt (builder of the Welland

Canal) knew Kerr and described him as “a very fine young man, tall and

handsome.” The Americans had a different perspective.

Still notorious to them was certain war atrocity, a massacre after a

guerrilla fight on Casper Corus’ farm outside Fort George in July 1813.

Two dozen overmatched rookie Americans were killed wantonly and

horrifically. While most sources I’ve consulted presume the incident

was perpetrated by western Great Lakes Native Americans under the

fearsome Potawatomi chief remembered only as “Black Bird,” many

American officers of the day had formed the impression that Kerr was

part of the party and were gunning for him ever after.

Kerr wisely refused to surrender to Willcocks or Porter, a couple guys

not directly answering to the chain of command. They would probably

have skinned him. Kerr held out till a squad of professional

soldiers–U.S. dragoons (mounted skirmisher-scouts)–showed up. While it

seems to me that the treatment of prisoners was way better in the local

1812 war than in much of World War Two, Kerr was lucky to make it to

that POW camp in Cheshire, Massachusetts. In fact, on the night word

got out that he was among the prisoners taken at Queenston, two

American Army officers, Major Henry Leavenworth of the 9th Regiment and

Captain George Howard of the 25th (the recently nicknamed, “Grey Doom”)

came to General Brown requesting the cheerful honor “to blow out Kerr’s

brains.” The request was denied.

3

Though camped back closer to his base, Brown was still spoiling for a

fight. At first he planned to stomp on up to Burlington, a move that

might force a battle on a larger scale. This was a time-tested

strategy; pick a mark valuable enough and anyone will come out

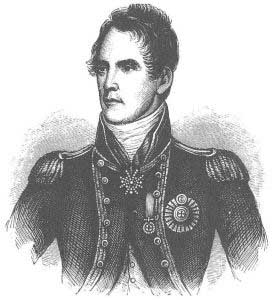

swinging. About the same time, Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond

(1772-1854) arrived from York (Toronto) to take personal control of

Fort George and all the Empire’s forces within range of the Niagara.

The storm clouds were finally gathering.

Gordon Drummond

Source: Wikipedia – public domain

Gordon Drummond

Source: Wikipedia – public domain

This

Gordon Drummond was the first native-born Canadian to

command both the army and the civil government and a far grimmer

customer than his predecessor, the universally admired Isaac Brock. No

warrior was ever more courageous than Brock, but what stood out in him

was his humanity. (It was reported once that he fought back tears at

having to watch the execution of insurgent soldiers.) Brock wasn’t just

a commander; he was a leader. Drummond prided himself on toughness, at

least with other people’s bodies. His regiment, the 8th or King’s (“The

Leather Hats”), had seen bloody action in Holland and served in the

West Indies, the Mediterranean and Egypt. The fire-breathing Drummond

had no qualms about massacres or executions. He loved bayonet charges,

and he wasn’t sitting still in a fort.

At mid-morning on July 25, Drummond sent Fort Niagara’s commander

Lieutenant Colonel John Tucker and some western Native warriors down

the Portage Road on the American side. (Both sides had one.) Nicknamed,

“Brigadier Shindy” (meaning possibly something like, “General

Disorder”), Tucker dislodged some New York volunteers at Youngstown and

destroyed cannon batteries at Lewiston that had been peppering Fort

George from over the river. Still on the Canadian side, General Jacob

Brown thought this might be the main British move: an attack on his

supply base at Fort Schlosser (Niagara Falls, NY). Some panicky scouts

certainly informed him so. Drummond also sent skirmishers and light

troops south out of his home base, Fort George. On the gorgeous

afternoon of July 25th, General Brown heard about the latter force.

Still suspecting that the full British move might be on the American

side of the Niagara, Brown ordered Winfield Scott and 1200 friends to

scatter these banditos back to Fort George, which he thought might ease

the squeeze on Fort Schlosser.

At about 5:30 Scott and his army headed north along the Portage Road.

If the Americans weren’t too abstracted, they would have enjoyed the

wondrous summer afternoon and some of the most inspiring scenery in the

nation. To their right were river, cliffs and falls, and the American

side still starting to rebuild from its winter torching. To their left

were fields, creeks and thick woods. The sloping sun sent hopeful light

into the clouds ahead over the lake.

Scott’s force passed through the hamlet of Bridgewater Mills just a bit

south of today’s Niagara Falls. Around a bend near Table Rock was the

tavern of “the Widow Willson,” a merry, politically neutral figure

whose establishment had been dispensing liquid conviviality since at

least 1795. Not hurting the ambience were her two svelte daughters,

Harriett and Statira, the latter (in the words of British Lieutenant

John Le Couteur) “the naiad of the Falls.” Widow and water-nymphs were

busily entertaining as Scott’s vanguard approached.

Just as Scott drew in sight, a handful of redcoat officers came out in

a hurry, hopped onto their horses, and headed up the road through the

woods to the north. The last of them paused, looked right at Winfield

Scott, and, like the pre-match handshake of tennis players, gave a

salute, which “Old Fuss and Feathers” returned. Because of his size,

uniform and position in the formation, Scott was recognizable even at a

distance. No further description was made of the redcoat who hailed

him, but if he was short and portly, he just might have been Riall. The

merry widow told Scott that he had missed happy hour with General Riall

and his staff, but that he was in time to join the full party up ahead,

with a couple thousand of Riall’s good friends.

Scott didn’t believe her. Still hoping he might catch up to Riall’s

entourage, he rushed up the road through the heavy trees and came out

upon open fields, a pair of roads, a modest hill, and an alarming

surprise: a full British army at Lundy’s Lane set up in battle

formation. What was going on? Scott had just taken a big bite out of

Riall’s army at Chippawa and, like the Hydra growing back a couple of

its heads, there it was again! Reinforced and reinvigorated, this was a

far bigger army than Scott had faced at Chippawa.

Lundy’s Lane was a dirt road that ran from the cliff above the Niagara

to the head of the Ontario. It met the Portage Road at a right angle on

a gentle slope a mile west of the river. A church was on the pinnacle,

and around it a cemetery and some open field. Riall’s brigade had

shadowed the Americans all the way from Queenston like it had done so

many times before that month. This time it had stopped and waited. The

redcoat line stretched out ominously on Lundy’s Lane. The little hill

by the church bristled cannon barrels.

As Scott’s forces set up at the edge of a wooded area, he saw that he

was in a bind. His outnumbered troops would take a beating from the

cannon. Here’s where all his drilling paid off. He deployed his brigade

into a tight defensive formation, sent messages for General Brown to

hustle on up with everything he had, and waited to see what would

happen.

Still following his orders not to engage, British Major General Riall

started taking his army apart and cautiously falling back. But top dog

Gordon (“cold steel”) Drummond and the sturdy 8th showed up from Fort

George. Their 3000 or so faced a game 1200 Americans, and Drummond was

sending for reinforcements himself.

Scott cursed the addled scouts who had called for help from Lewiston.

The Americans had fallen for the feint. The main British strength in

Ontario was set up right in front of him, and here he stood facing it

like a gunfighter with his hand at his side, staring down Sundance and

well aware that the slightest move had better be the right one. What to

do about it now? As he studied his position amid the companies of men,

the wheels were turning rapidly in the mind of General Scott. Crowing

at the high ground like a grade school geek from behind the newfound

protection of the bully, Scott’s opponents didn’t all judge his moments

of introspection charitably. “Dread seemed to forbid his advance and

Shame to forestall his retreat,” wrote Mohawk Scotsman John Norton in

his reflections of the day. If those indeed were Winfield Scott’s two

shoulder-angels, dread would be the first to flinch. The bloodiest

three hours in Canadian history were commencing.