Richard Upjohn - Table of Contents

Richard Upjohn

and the Gothic Revival in Buffalo

By Dr.

Frank Kowsky

Originally published in the Preservation Coalition of Erie County's newsletter, Preservation Report, March/April 1986, Vol. 8 No. 2

Even before its consecration in 1846, Richard Upjohn's Trinity Episcopal Church in New York City had established the reign of Gothic in American religious architecture. It had also provided Upjohn with a formidable reputation.

Two years after Trinity opened, the vestrymen of St. Paul's in Buffalo

formed a building committee to erect a new stone church. They

immediately instructed its members to engage Upjohn as architect. The

major Episcopal church in the largest commercial industrial center in

upstate New York, St. Paul's could not escape comparison with Trinity.

Upjohn was the logical, and safest, choice.

At

his initial meeting with the building committee in March, 1848, Upjohn

presented a plan for a church that would hold one thousand worshippers.

The committee, however, found the scheme too expensive. Nonetheless,

they liked the ground plan and pressed Upjohn for less elaborate

elevations. One year later, the more economical version, embodying a

nave 105 feet long with aisles on either side, won their approval. In

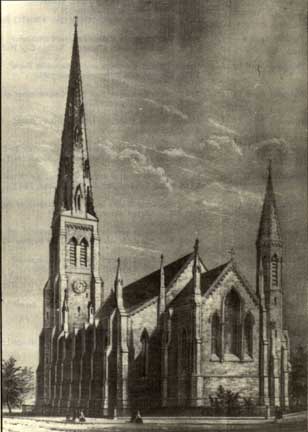

1851. in order to raise money for chimes. the parish sold lithographs

of the architect's perspective views of the new church.

At

his initial meeting with the building committee in March, 1848, Upjohn

presented a plan for a church that would hold one thousand worshippers.

The committee, however, found the scheme too expensive. Nonetheless,

they liked the ground plan and pressed Upjohn for less elaborate

elevations. One year later, the more economical version, embodying a

nave 105 feet long with aisles on either side, won their approval. In

1851. in order to raise money for chimes. the parish sold lithographs

of the architect's perspective views of the new church.

Construction began in the Spring of 1850. That is, immediately after

another denomination bought and moved the old Carpenter

Gothic church that since 1821 had stood on the site of the present

edifice at Church and Pearl Streets. Economy, a persistent

consideration with the congregation, dictated the use of red Medina sandstone from

nearby Orleans County, instead of the gray limestone Upjohn had first

proposed. The choice was a happy one, and may have inspired H. H. Richardson

two decades later to use the same material for his first large

'Richardsonian'' building, the Buffalo State Hospital.

Complete in its essentials, St. Paul's was consecrated in October 1851.

The tower, which resembles that of St. Paul's, Brookline,

Massachusetts, on which Upjohn worked at the same time as the Buffalo

church, took until 1870 to finish. At the service of consecration, the

rector, Dr. William Shelton, praised Upjohn profusely. But he

also reflected a penchant for overspending. "A refined, cultivated, and

religious taste has been here," said Shelton,

giving to, every object and to every part, to every line the impress of cultivated architectural skill. The cost has far exceeded, nearly doubled, his design and our intent. It has been his infirmity, and we may pardon that infirmity, in consideration of the surpassing beauty he has achieved.

The rector's indulgence notwithstanding, the building committee a few days later exacted a promise from Upjohn that the total bill for the church would be under $85,000. He further agreed to take his five percent commission on only the original estimate of $52,000.

Features of the Church

Although his earliest proposal had included a tower reminiscent of Trinity's, from the very beginning Upjohn designed St. Paul's differently from its famous forbearer. Encouraged by the triangular shape of the sloping site, he rejected the symmetry of the Manhattan church. St Paul's tower stands at the southwest corner and a two-story chapel, three bays long, adjoins the north aisle. In addition to greater picturesqueness, the Buffalo church displays more strictly than Trinity the principles of ecclesiology, the science of church building that dictated the architectural requirements for Anglo-Catholic ritual. The altar, for example, is at the eastern end of the building. Moreover, St. Paul's, built with hammer dressed random ashlar, is Early English, the style of the thirteenth century which had come to be esteemed as a purer form of Gothic than the late Medieval Perpendicular style in which Trinity is cast.

But the major ecclesiologial advance over Trinity is the design of

the chancel, the most important liturgical area of the church.

As correct ecclesiology demanded, it is distinguished externally by a

lower roofline than that of the nave, which it terminates. Upjohn

further called attention to the sanctuary by placing a bell turret near

it at the northeast angle of the building. To churchmen of the 1850s,

the back of St. Paul's gave notice of an up to date parish.

The skill with which all of these elements -- asymmetry, irregular

stonework, Early English style, and low chancel -- are united

proclaims St. Paul's the fully evolved example of a mode of a church

design Upjohn had embarked upon in such post-Trinity works as the

Church of the Holy Communion (1846), New York City, St. Mary's (1846),

Burlington, New Jersey, and Grace Church ( 1847), Brooklyn. Trinity

Church had made America aware of the movement to reinspirit Gothic

architecture that had advanced to maturity in England under the banner

of Pugin; St. Paul's confirmed that, since Trinity, America's most

well-known religious architect had moved beyond the Gothic Revival

based on Pugin to embrace the Parish Church Revival fostered by the

Ecclesiological Society, the American branch of which thought highly of

Upjohn. Upjohn's recognition of his achievement may have prompted the

statement attributed to him that he regarded St. Paul's as his best

ecclesiastical work.

Inside,

St. Paul's possessed the openness of a hall church, for there was no

clerestory and the aisles reached almost to the height of the nave. The

feeling of spaciousness, which was characteristic of Upjohn's

metropolitan churches, gained impressively from the two-story chapel

extending off of the north aisle. A hammerbeam roof, the boarding of

which was painted dark blue and decorated with gold stars, covered the

nave. Although the imitation plaster vaulting of Trinity Church was

avoided, sham was nonetheless present: the piers and arches of the nave

arcades were wood painted the color of the exterior stone. The stained

glass was described as being of a ''rich salmon color.''

Inside,

St. Paul's possessed the openness of a hall church, for there was no

clerestory and the aisles reached almost to the height of the nave. The

feeling of spaciousness, which was characteristic of Upjohn's

metropolitan churches, gained impressively from the two-story chapel

extending off of the north aisle. A hammerbeam roof, the boarding of

which was painted dark blue and decorated with gold stars, covered the

nave. Although the imitation plaster vaulting of Trinity Church was

avoided, sham was nonetheless present: the piers and arches of the nave

arcades were wood painted the color of the exterior stone. The stained

glass was described as being of a ''rich salmon color.''

The Church as Architectural Landmark

Predictably, local citizens touted

St. Paul's as the finest house of worship in the state outside of New

York City. Buffalo, the "Queen City of the Lakes," had its first

architectural landmark. Situated a short distance from the terminus of

the Erie Canal and within a few blocks of Lake Erie, St. Paul's

symbolized the progressive spirit of the young city which enjoyed

growing prosperity from its pivotal location between the farmlands and

resources of the west and the markets and industry of the east. In 1866

Upjohn's beautiful church was the natural choice to become the

Episcopal Cathedral tor the new Diocese of Western New York, a function

it continues to perform.

Other WNY Upjohn Churches

St. Paul's was Upjohn's most important ecclesiastical commission

in Western New York, but not his only one. In addition to churches in

Rochester, Niagara Falls, Mayville, and Jamestown, he is also

identified with two rural churches of considerable charm. These are

board and batten structures of the kind he and John Weller Priest (d.

1859) designed in the late 1840s and early 1850s with the blessing of

the New York Ecclesiological Society, which looked upon them as

acceptable substitutes where masonry construction proved too expensive.

St. John Episcopal Church on Main Street in the Niagara River town of

Youngstown is believed by local tradition to be by Upjohn. However, the

date of consecration, in 1878—by which time Upjohn had been retired

from active practice for many years—suggests that Richard Michell

Upjohn (1827-1903), the architect's son and successor, may have been

responsible. Correspondence dated December 30, 1853, confirms the

senior Upjohn's involvement with Trinity Episcopal Church (consecrated

in 1854) in Warsaw. The chapel closely resembles the "cheap but still

substantial'' wooden church for which Upjohn supplied specifications

and working drawings in his book Upjohn's Rural Architecture, which

appeared in 1852. Trinity seems to have been typical of many churches

built by distant parishes following Upjohn's published advice along

with written suggestions he sent by mail. Asking little or no

compensation, he acted from a sincere desire to improve the conditions

of rural churchgoing.

St. Paul's Burns

Richard Upjohn died in 1878 knowing that

St. Paul's epitomized the Gothic Revival on the Niagara Frontier.

Unfortunately, a decade after his death, fire, the scourge of Gothic

and Gothic Revival builders alike, nearly destroyed his masterpiece;

the interior, with its wooden arcading, was gutted.

Late in the summer of 1888 Robert W. Gibson (1854-1927) took charge of

repairing the damaged building. Gibson, like Upjohn an Englishman, had

immigrated to this county in 1881. He had made his name two years

later, when, in competition with H.H. Richardson, he had won the

commission for All Saints Cathedral in Albany. For all of 1889 he

supervised the work at St. Paul's. On January 3, 1890, the church

reopened with the service of Reconciling and Hallowing.

Retaining the original walls, which had remained sound, Gibson

introduced only minor changes to the exterior. The freestanding tower

escaped the blaze and stands today unaltered from Upjohn's time. It

still lifts its majestic spire 270 feet into the air, well above its

newer and more famous ''skyscraper" neighbor across the street,Louis Sullivan's Prudential

(Guaranty) Building (1894).

Gibson concentrated his efforts on rebuilding the interior which he

succeeded in making more substantial, spacious, and ornamental than it

had been before the fire. The rebuilt structure so impressed George

Shinn, the nineteenth century chronicler of Episcopal architecture,

that

in King's Handbook of Notable Episcopal Churches he attributed it

entirely to Gibson; Upjohn received only passing reference.

Nonetheless, Gibson's work was more of a sympathetic revision than a

drastic alteration of the previous design. Using stone instead of wood

for the structural parts, he preserved the basic outlines of the

original ground plan (nave,

aisles, and north chapel) but made the chancel longer and wider

and added a clerestory.

The most notable deviation from Upjohn occurs in the final bay of the nave arcade where two oversized

arches, described as transept

arches, rise to the roof, interrupting the clerestory. Together with

the chancel arch of the same height, they define before the sanctuary a

lofty area that majestically dominated the interior. The church does

not actually have fully developed transepts, for the gabled "arms'' do

not project beyond the aisles, and the hammerbeam roof, the new feature

that comes closest to reproducing Upjohn's original design, extends to

the chancel without a crossing. The pseudo-transepts, as they might be

called, were contrived not to provide more room at ground level, but to

impart to the ceremonial end of the church an air of expansiveness.

Gibson also took the opportunity afforded by the fire to endow St.

Paul's with that special charm possessed by Medieval buildings that

have various parts in different styles. More disposed toward

archaeological picturesqueness than the cautious ecclesiologists of

Upjohn's day, Gibson introduced conspicuous details from the Decorated

style of English Gothic.

Most obviously are the foliated capitals in the nave arcade (and

elsewhere) that replaced the simply molded ones of Upjohn's design and

the striking traceried window that now fills the end wall of the

chancel where earlier existed triple lancets. Gibson carefully

integrated his Decorated portions with what survived from the first

church. In so doing he insured that St. Paul's, erected in the style of

the thirteenth century and rebuilt in the style of the fourteenth

century, remained the Niagara Frontier's finest church of the

nineteenth century.